Regulations Amending the Motor Vehicle Safety Regulations (School Buses): SOR/2024-239

Canada Gazette, Part II, Volume 158, Number 26

Registration

SOR/2024-239 November 29, 2024

MOTOR VEHICLE SAFETY ACT

P.C. 2024-1265 November 29, 2024

Her Excellency the Governor General in Council, on the recommendation of the Minister of Transport, makes the annexed Regulations Amending the Motor Vehicle Safety Regulations (School Buses) under subsections 5(1)footnote a and 11(1)footnote b of the Motor Vehicle Safety Act footnote c.

Regulations Amending the Motor Vehicle Safety Regulations (School Buses)

Amendments

1 Subsection 15.1(1) of the Motor Vehicle Safety Regulations footnote 1 and the heading before it are repealed.

2 Section 17 of the Regulations is repealed.

| Column I Item (CMVSS) |

Column II Description |

|---|---|

| 111 | Mirrors and Visibility Systems |

4 The heading “Mirrors and Rear Visibility Systems” before section 111 of Schedule IV to the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Mirrors and Visibility Systems

5 (1) Paragraph 111(25)(f) of Schedule IV to the Regulations is replaced by the following:

- (f) all of the still or video camera observations shall be done with the service door of the bus closed and all stop signal arms fully retracted; and

(2) The heading before subsection 111(29) of Schedule IV to the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Visibility Systems

Rear Visibility Systems

(3) Section 111 of Schedule IV to the Regulations is amended by adding the following after subsection (33):

Perimeter Visibility Systems

(34) Every school bus other than a multifunction school activity bus must be equipped with a perimeter visibility system that conforms to the requirements set out in Document No. 111 — Perimeter Visibility Systems (Document 111), as amended from time to time.

(35) The perimeter visibility system must include a device that displays to the driver in real time at most two images of the area that is immediately beyond the perimeter of the school bus and that would be, without the system, difficult or impossible for the driver to see. The boundaries of the area must be determined in accordance with Document 111.

(36) The device must be securely mounted in the driver’s forward field of view and must not obstruct the driver’s view of the road or of any controls or displays.

(37) The device must automatically display the images and must only do so when the school bus’s propulsion system is activated and the school bus is fully stopped or travelling at a speed less than 15 km/h. However, the device may display the images when the school bus’s propulsion system is deactivated.

Transitional Provision

(38) Until November 1, 2027, a school bus referred to in subsection (34) may conform to the requirements of this section as it read on the day before the day on which this subsection comes into force.

6 (1) Subsection 131(1) of Schedule IV to the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Application

131 (0.1) This section applies to school buses other than multifunction school activity buses.

Stop Signals

(1) Every school bus must be equipped with one or two stop signal arms that conform to the requirements of Technical Standards Document No. 131, School Bus Pedestrian Safety Devices (TSD 131), as amended from time to time.

(2) Section 131 of Schedule IV to the Regulations is amended by adding the following after subsection (2):

Image Recording System

(3) If the school bus is equipped with a system that is intended to record images of a vehicle that is passing the school bus when the red signal warning lamps referred to in Table I-a of Technical Standards Document No. 108, Lamps, Reflective Devices, and Associated Equipment are activated, the system must

- (a) be placed in a manner that allows the system to record images of the vehicle’s rear licence plate;

- (b) record the images automatically; and

- (c) operate in temperatures from −40°C to 40°C.

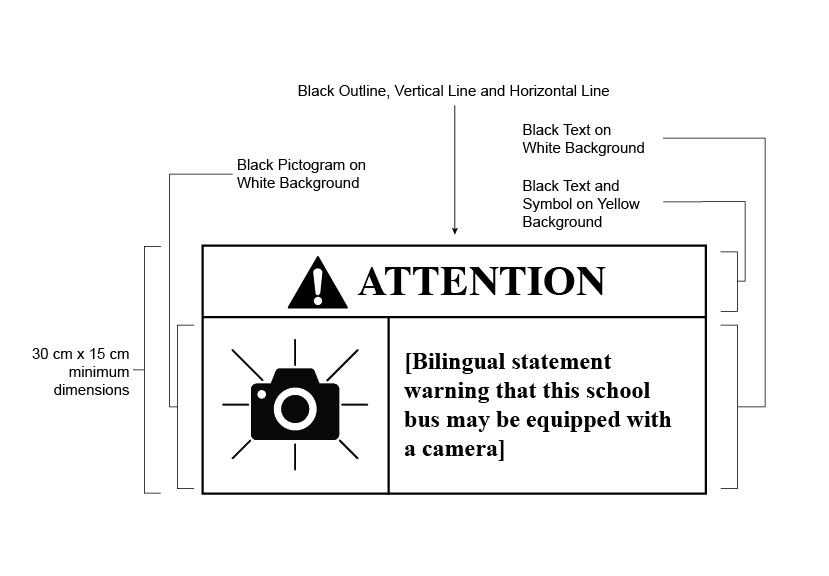

(4) Whether or not the school bus is equipped with the system referred to in subsection (3), a label, as shown in Figure 1, must be permanently affixed to the school bus so that the label is readily visible to a driver who is behind the school bus.

Figure 1

Figure 1 - Text version

White rectangle with black border, text, lines and symbols. At the top of the rectangle above a horizontal line: a triangle with an exclamation mark centered in it and, to the right of the triangle, the word “ATTENTION”. Below the horizontal line: a camera to the left of a vertical line and, to the right of the vertical line, in brackets, the words “Bilingual statement warning that this school bus may be equipped with a camera”.

Transitional Provision

(5) Until November 1, 2027, a school bus referred to in subsection (0.1) may conform to the requirements of this section as it read on the day before the day on which this subsection comes into force.

Coming into Force

7 These Regulations come into force on the day on which they are published in the Canada Gazette, Part II.

REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS STATEMENT

(This statement is not part of the Regulations.)

Executive summary

Issues: According to the National Collision Database (NCDB) statistics, school buses are the safest way to transport children to and from school, more so than any other form of transportation including walking, cycling or by passenger vehicle. Despite their excellent safety record, data from 1998 to 2019 indicates that, every year, an average of three children and vulnerable road users (VRUs) are fatally injured, and ten major injuries are reported in collisions with a school bus or collisions with a passing vehicle while in the immediate vicinity of a school bus in Canada.

Description: The Regulations Amending the Motor Vehicle Safety Regulations (School Buses) (the Regulations) will require school buses to be equipped with an exterior perimeter visibility system consisting of a series of cameras that provide visibility around the exterior of the school bus and a monitor to display the views to the driver. In addition, the Regulations set minimum requirements that will apply to image recording systems (hereinafter referred to as infraction cameras), if voluntarily installed on school buses.

In addition, subsection 15.1(1) and section 17 of the Motor Vehicle Safety Regulations (MVSR) are repealed to better align with amendments made under the Motor Vehicle Safety Act (MVSA) in 2014.

The Regulations will come into force on the date of publication in the Canada Gazette, Part II; however, there will be a transitional period, so that the requirements regarding exterior perimeter visibility systems and infraction cameras will not be mandatory until November 1, 2027.

Rationale: Since January 2019, the Task Force on School Bus Safety has met to share information and expertise on all aspects of school bus safety. In February 2020, the Task Force published a Report of the Task Force on School Bus Safety (PDF), which made specific technical recommendations for improving school bus safety. The work of the Task Force informed the development of the Regulations, which would introduce new technology requirements for school buses that are expected to better protect children in and around school bus loading areas.

The Regulations were prepublished in the Canada Gazette, Part I, on July 2, 2022.

In comments received from stakeholders about the Regulations, there was a consensus about improving the safety of children. However, stakeholders also raised questions and concerns about the readiness and effectiveness of the new technologies and the relative costs and benefits of requiring the use of these technologies. Some stakeholders suggested that, for clarity and certainty, the Regulations should be more prescriptive about technical requirements. Stakeholders also requested lead time to allow for the testing and installation of new technologies before the requirements come into force. In response to stakeholder comments, several changes were made to the Regulations. For example, requirements around extended stop signal arms for school buses, which were included at prepublication, have been removed.

The net cost of the Regulations is estimated to be $144.8 million. The estimated costs of the Regulations are $196.0 million in present value between 2024 and 2036 (7% discount rate, 2023 Canadian dollars), of which $154.9 million would be associated with capital and installation costs and the remaining $41.1 million would be due to maintenance costs. The Regulations are expected to result in both monetized and non-monetized benefits. The benefits encompass reducing fatalities and injuries around school buses through additional safety standards, as well as broader societal, environmental, and mental health advantages as a result of the adaptation of the proposed technologies. The monetized benefits are estimated at $51.1 million in present value between 2024 and 2036 (7% discount rate, 2023 Canadian dollars).

Despite the fact that the estimated monetized costs outweigh the monetized benefits, Transport Canada believes that the Regulations are in the public interest because of the overall anticipated safety and mental health benefits, both qualitative and quantitative, for children, their families, and their communities.

The one for one rule does not apply as there is no incremental change in administrative burden on business and no regulatory titles are repealed or introduced. Furthermore, analysis under the small business lens concluded that the Regulations will not impact Canadian small businesses.

Issues

Although school buses are the safest way to transport children to and from school, they are not without safety risks. Despite the excellent safety record of school buses, data from 1998 to 2019 indicates that, every year, an average of three children and VRUs are fatally injured and ten major injuries are reported in collisions with a school bus or collisions with a passing vehicle while in the immediate vicinity of a school bus in Canada.

Every school bus collision has a detrimental impact on more than just those directly involved in the collision. School bus collisions negatively affect the mental and emotional wellbeing of school-aged children, their peers, their families, and the greater community.

New technologies have been developed that can be used on school buses to assist in improving safety around school buses.

Regulatory intervention is needed to prescribe the use of new technologies to improve school bus safety, thereby reducing the risk of injuries and fatalities.

Regulations are also needed to repeal subsection 15.1(1) and section 17 of the MVSR, which pertain to naming conventions for test methods published by Transport Canada and notices published in the Canada Gazette for updates to technical standards documentsfootnote 2 (TSDs), respectively, in order to better align the MVSR with amendments made to the MVSA in 2014.

Background

School bus safety is a shared responsibility with federal/provincial/territorial governments, school boards and school bus operators each playing a role. Under the MVSA, Transport Canada is responsible for the administration and enforcement of the MVSR, which include specific requirements for newly manufactured or imported school buses. In Canada, the vehicle manufacturer or importer must certify that all vehicles imported to Canada, or manufactured in one province and sold in another, comply with all applicable safety regulations and standards. Transport Canada does not have jurisdiction over aftermarket modifications or retrofitting of school buses. Provinces and territories are responsible for the enforcement of safety on Canada’s roads and highways, for the driver and vehicle licensing, the rules of the road and aftermarket vehicle modifications. Legislation can vary from one province to another.

Federally governed by some 40 Canadian Motor Vehicle Safety Standards under the MVSR, school buses have a series of structural safety features that are specifically designed to safeguard children in the event of a collision in addition to pedestrian safety features to help prevent injuries to VRUs outside the bus. That said, the Government of Canada is always searching for ways to improve road safety. Therefore, on October 15, 2018, the Minister of Transport asked Transport Canada to take a fresh look at school bus safety. As part of this fresh look, Transport Canada reviewed available literature and existing technologies for improvements that could benefit safety both inside and outside the school bus.

On January 21, 2019, the Council of Ministers Responsible for Transportation and Highway Safety (the Council of Ministers) established a Task Force on School Bus Safety using a two-tiered governance model to support a cohesive, national approach to school bus safety. Specifically, a Steering Committee consisting of federal, provincial, and territorial government representatives was established along with an Advisory Panel consisting of manufacturers, school board representatives, school bus fleet operators, labour unions and safety associations. Their mandate was to review safety standards and operations, both inside and outside school buses, and to identify where school bus safety could be further strengthened.

On June 20, 2019, the Task Force’s preliminary report (PDF) was posted on the Council of Ministers’ website, identifying a range of opportunities to further strengthen school bus safety. Informed by the results of its broad review, the Task Force recognized that opportunities exist to help make school buses even safer. To achieve an increased level of safety, the Task Force identified a series of countermeasures that would need to be taken in three key areas: driver assistance, safety features outside the bus, and occupant protection.

In February 2020, the final Report of the Task Force on School Bus Safety (PDF) was posted on the Council of Ministers’ website. Consistent with the direction from the Council of Ministers, the Task Force identified a shortlist of opportunities to further improve school bus safety. The supporting evidence confirmed that school children are at greater risk in or near school bus loading zones than they are as school bus passengers. Indeed, according to the report, 79% of school-aged fatalities involving a school bus occurred outside the bus, in or near school bus loading zones. The Task Force focused on developing recommendations to address this reality. Specifically, the Task Force submitted that consideration be given to adding the following safety features to school buses, and encouraged all jurisdictions to explore the application of these measures:

- Infraction cameras are a means to deter motorists from passing a school bus when its red signal warning lamps are flashing, as this is when children may be crossing the street in front of the school bus. Infraction cameras would help deter passing motorists and thereby prevent potentially dangerous incidents;

- Extended stop signal arms serve as a visual stop signal to motorists approaching a school bus from both the front and rear of the bus. The extended stop signal arm may also serve as a physical barrier to prevent vehicles from passing the school bus and act to further deter motorists from passing school buses while children are entering or leaving the school bus;

- Exterior 360° cameras, herein referred to as perimeter visibility systems, help the driver of a vehicle identify if any VRUs, such as children, are around the vehicle while the vehicle is stopped or travelling slowly, preventing incidents where the school bus would collide with an unseen VRU. These systems feature a series of cameras installed on the vehicle and a monitor to display the images to the driver. The cameras provide views around the vehicle which are difficult to obtain with mirrors alone; and

- Automatic emergency braking is an advanced driver assistance system designed to monitor the area in front of the vehicle when it is in motion, provide a warning to the driver in the case of a potential collision, and automatically apply the vehicle brakes if an imminent crash is detected and the driver is not responding to the situation, all to help avoid collisions with pedestrians, cyclists or other vehicles.

Following the February 2020 Report, three school bus pilot projects were launched in 2020 in collaboration with Transport Canada (two in British Columbia and one in Ontario involving a total of six school buses), in order to assess operational considerations for the use of seat belts on school buses, as well as to validate the Guidelines for the Use of Seatbelts on School Buses developed by the Task Force on School Bus Safety. While the emphasis was on the study of seat belt use, some of the above-mentioned technologies were also installed on the buses (based on jurisdictional interest) as part of the pilot projects. In parallel, research to evaluate the safety performance of automatic emergency braking and field of view of perimeter visibility systems was conducted at Transport Canada’s Motor Vehicle Test Centre in Blainville, Quebec. For those buses equipped with an infraction camera, extended stop signal arm or perimeter visibility systems, Transport Canada took the opportunity to have driver experiences and observations recorded. These pilot projects were initially slated to run for one full academic year (the period of the year during which students attend an educational institution, usually from September to June of the following year). Due to disruptions caused by measures implemented to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic, the pilot projects ended in July 2023. While a final report is not expected until 2025, preliminary findings suggest that extended stop signal arms, infraction cameras, and exterior visibility camera systems may have a positive impact on strengthening school bus safety; however, the sample size of vehicles used did not provide enough evidence to quantify the effectiveness of these technologies.

Extended stop signal arm

Extended stop signal arms are currently available as aftermarket products from third-party companies, but not from school bus original equipment manufacturers (OEM).footnote 3 The extended stop signal arm has a similar function to the current stop signal arm required on school buses, with the main difference being that it is meant to extend further outward when deployed, to serve as a physical barrier to prevent vehicles from passing the school bus. There are no provisions in the Canadian Motor Vehicle Safety Standard (CMVSS) 131 — School Bus Pedestrian Safety Devices (CMVSS 131) or the technical requirements of Technical Standards Document (TSD) 131 — School Bus Pedestrian Safety Devices (PDF) (TSD 131) that expressly prohibit the installation of an extended stop signal arm on new school buses. TSD 131 does not limit the length of a stop signal arm when it is deployed, but rather, it sets minimum dimensions for the stop signal and letters, outlines reflective material and lighting requirements, and indicates the location of installation on the driver’s side of the school bus.

A stop signal arm is defined in TSD 131 as “a device that can be extended outward from the side of a school bus to provide a signal to other motorists not to pass the bus because it has stopped to load or discharge passengers.” An extended stop signal arm is a stop signal arm that extends out further than the “normal” stop signal arm to make it more difficult for a vehicle to pass a school bus with this device deployed, and to provide a more obvious signal to motorists not to pass the school bus because it has stopped to load or unload passengers; it is meant to increase conspicuity of the stop signal over and above the current stop signal arm.

At present, extended stop signal arms have not yet been demonstrated to be the best or only solution to achieve the goal of preventing illegally passing vehicles and increasing the conspicuity of the stop signal. More work is required to determine if extended stop signal arms or another safety technology or approach could help achieve the safety objective. Therefore, Transport Canada has decided not to pursue a requirement that school buses be equipped with extended stop signal arms at this time.

Perimeter visibility systems

A perimeter visibility system is meant to help the driver of a vehicle identify if any VRUs, including children, are around the vehicle while the vehicle is stopped or travelling slowly. This identification is achieved by providing the driver with a series of images of the surrounding area and may include an aerial overview of the vehicle, so that the driver may see VRUs. These systems feature a series of cameras installed on the vehicle and a monitor to display the image to the driver. The cameras provide the driver with views around the vehicle which would otherwise be difficult for the driver to see directly or by using mirrors. Prior to these Regulations, some school bus manufacturers offered their own versions of perimeter visibility systems as an option on their new school buses. Other perimeter visibility systems have also been available as aftermarket systems by third-party manufacturers. Prior to the making of these Regulations, there were no requirements in North America or internationally that obliged school buses to be fitted with this type of technology.

The positioning and images displayed to the driver on the display system vary among manufacturers. Systems may display views to the driver when the vehicle is starting to move from a stopped position, when the vehicle is about to make a turn (left or right, where the appropriate view can be shown on the display) and/or when the vehicle is in reverse. The vehicle operators may also toggle between different views on the display. The aerial overview, that may also be generated and displayed to the driver by the perimeter visibility system, generates a synthetic image that digitally stitches together images captured by cameras placed on the exterior of the school bus.

Because of their size and design, school buses have many areas around their periphery where visibility for the driver is only partial or even zero. These areas are generally referred to as the “danger zone.” It can be extremely difficult for a school bus driver to detect VRUs in the “danger zone.” To help detect children and other VRUs, school buses are fitted with different types of mirrors; however, visibility around the entire perimeter of a school bus remains an important road safety issue. Transport Canada had its road safety team at Polytechnique Montréal conduct visibility tests on two school buses to establish baseline visibility patterns, which were subsequently used to evaluate the performance of various perimeter visibility systems installed on newly manufactured school buses by the OEM, and to support the development of the Regulations.

Both vehicles studied were equipped with the same number of cameras on the sides, front and rear of the vehicle and were positioned similarly on the vehicles. Both buses were also capable of displaying the individual image of each of the cameras in addition to the synthetic aerial overview image produced by stitching together the individual camera views. During the indirect visibility testing conducted, it was determined that the synthetic aerial overview produced from the individual camera images was severely distorted and afforded only a very limited view of the total area visible to the individual cameras themselves. For this reason, the usefulness of the synthetic aerial overview was very limited. A child present around the perimeter of the school bus may not be visible on the synthetic aerial overview displayed to the driver because the stitching of the image leads to blind spots on the visual display.

Based on this analysis, in order to help increase the driver’s visibility of the area surrounding the perimeter of the school bus, it would have been more useful to show images from the individual cameras on the driver’s display rather than the aerial overview which resulted in blind spots. The aerial overview provided by these perimeter visibility systems would therefore need to be improved to provide a comprehensive picture for safety purposes. For this reason, the Regulations require that a perimeter visibility system provide a view of a defined area around a school bus. Any combination of images can be used to provide this view as long as the requirements of visibility of a test tool are met.

Regarding the display component of a perimeter visibility system, Transport Canada published Guidelines to Limit Distraction from Visual Displays in Vehicles in 2019 in order to address distraction from visual displays installed in a vehicle. The underlying premise for these guidelines is the need to fully consider what contributes to distraction. This means examining the device or system the driver is using, how the driver interacts with that device, the task they are doing, the duration of the interaction and the context of the device’s use to determine the level of potential distraction. The guidelines apply to visual displays that drivers may use while their vehicle is in motion such as the display of the perimeter visibility system. It is important to note that visual displays which help the driver with the driving task are not considered to be causes of distraction as they benefit the driver. The displays of these types of systems are currently used only during specific conditions under which the risk of a VRU in a blind spot of a vehicle are highest.

Infraction camera

At present, infraction cameras are an aftermarket product that have been installed on certain school buses in some jurisdictions in Canada, based on a needs assessment conducted by the individual jurisdictions. Prior to the making of these Regulations, there were no federal standards under the MVSR that applied to this equipment or its installation, nor were there any federal standards under the MVSR that would prevent the installation of such equipment on a school bus. Infraction cameras are not currently installed on new school buses by any OEM.

In certain jurisdictions, school bus drivers are required to manually note the licence plate of a vehicle that illegally passes their school bus and to report this information as appropriate. Such a task can be distracting for the driver. In many cases, drivers are not able to capture this information and, as a result, most violations go unreported.

Infraction camera technology has the potential to improve road safety for VRUs, including school children, by deterring vehicles from illegally passing a stopped school bus with its red signal warning lamps flashing. The camera is part of a broader enforcement system to deter illegally passing vehicles and to prosecute violations defined within provincial/territorial/municipal jurisdictions as applicable. Various strategies may be used to inform motorists of the use of infraction cameras in a particular jurisdiction, including but not limited to information campaigns, labelling on school buses, and informational pamphlets sent out with issued fines for infractions. There is no single standard practice regarding these strategies, and jurisdictions implementing infraction cameras must assess what is best for their circumstances.

Infraction camera systems work by capturing a video or image of a vehicle passing a stopped school bus with its red signal warning lamps flashing. The infraction camera may facilitate the reporting of violations that occur around every school bus on which the technology is installed, thereby increasing the ability of enforcement officers to fine drivers and/or educate drivers of safe driving practices and the rules of the road around a school bus.

Passing a stopped school bus with its red signal warning lamps flashing is a violation in every Canadian province and territory. Violations are defined by the respective provincial or territorial highway traffic acts and, therefore, are enforced by law enforcement in the respective jurisdictions. As violations are defined by provinces and territories, the requirements, allowances, and other legislation around infraction cameras vary in different jurisdictions. Jurisdictions that choose to make use of infraction camera systems need to have an enforcement strategy in place with local or provincial law enforcement.

Other amendments

The change made to the MVSA in 2014, under subsection 11(3), allows for a technical or explanatory document produced by the Minister (including specifications, classifications, illustrations, graphs, test methods, procedures, operational standards and performance standards) to be incorporated by reference in the MVSR. Section 15.1(1) of the MVSR, which was created prior to the 2014 MVSA amendment, requires a prescribed naming convention for test methods. This type of naming requirement is not present in the MVSR for any other type of document produced by the Minister that may be incorporated by reference. The MVSR incorporate by reference many technical standards and test methods, all of which follow the same style for naming, description, and identification. Due to the 2014 MVSA amendment allowing a broader incorporation by reference power, section 15.1(1) of the MVSR is no longer required and the naming convention is unnecessarily restrictive.

The MVSA also allows for the incorporation by reference of TSDs. Currently, section 17 of the MVSR requires that Transport Canada publish a notice in the Canada Gazette, Part I, each time it amends a TSD. The 2014 MVSA amendments added subsection 12(3), which clarifies that TSDs do not need to be published in the Canada Gazette. Since the MVSA does not require TSDs to be published in the Canada Gazette, and due to the fact that Transport Canada has been utilizing a new and more effective process for notifying stakeholders of updates to TSDs (namely, publishing a notice on Transport Canada’s consultation webpage), section 17 of the MVSR is no longer needed.

Objective

The objective of the Regulations is to better protect school children outside and around school buses.

The Regulations will mandate that all newly manufactured school buses subject to the MVSA be equipped with exterior perimeter visibility systems. The goal of mandating this technology on school buses is to support the driver by providing a means of better detecting children, and other VRUs, around the exterior of the bus to avoid death and serious injuries. The perimeter visibility system is expected to provide the driver with appropriate views of the danger zones around a school bus in which a VRU would otherwise be hidden from view of the driver.

Infraction camerasfootnote 4 are a means to deter motorists from passing a school bus when its red signal warning lamps are flashing, as this is when children may be crossing the street in front of the school bus. The technology is essentially an enforcement tool for identifying violations defined under provincial and territorial Highway Traffic Acts. This technology on school buses offers increased vehicle safety by acting as a deterrent for motorists from passing stopped school buses, thus avoiding potential death and serious injuries to children and other pedestrians while they are crossing the street in front of the buses. By introducing requirements that apply only if the technology is installed on new school buses, it is Transport Canada’s intention to avoid impeding individual system requirements that may be set by jurisdictions, while highlighting the potential safety benefit of the technology for deterring illegally passing vehicles.

In addition, the Regulations will align the MVSR with amendments made to the MVSA in 2014 by repealing subsection 15.1(1) and section 17 of the MVSR, which pertain to naming conventions for test methods and notices published in the Canada Gazette for updates to TSDs, respectively.

The Regulations are expected to improve safety for school-aged children while also introducing qualitative benefits related to reducing societal toll and emotional distress for communities that may be affected by incidents involving a school-aged child and a school bus. Improvements to school bus safety can also improve public perception of school buses and their use for transporting school-aged children.

Description

The Regulations will require new school buses to be equipped with an exterior perimeter visibility system, including a monitor, to display views to the driver. In addition, the Regulations set requirements that apply to infraction cameras on school buses if they have been voluntarily installed.

CMVSS 111 sets installation and visibility requirements for mirrors on a broad range of vehicles including requirements for mirrors on school buses. The Regulations will mandate that school buses be equipped with perimeter visibility systems, and rename CMVSS 111, where the requirements for this technology reside within the MVSR, to the more general title “Mirrors and Visibility Systems” from “Mirrors and Rear Visibility Systems.” The Regulations incorporate a new standards document, Document 111 — Perimeter Visibility Systems. Document 111 specifies the area around a school bus within which a defined test tool must be visible and displayed to the driver by the perimeter visibility system. Document 111 also specifies requirements for the field of view to be provided to the driver; prescribes the test conditions for the system; identifies how to establish the visibility zone around the school bus; prescribes the dimensions of the test tool to be used for testing; and sets out the operating requirements for the display unit.

On the date that the Regulations are published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, Transport Canada will email Document 111 and the Regulations to stakeholders. In addition, Document 111 will be posted and made available on Transport Canada’s website as of the day that the Regulations are published in the Canada Gazette, Part II.

The Regulations also establish requirements that will apply to infraction cameras if they are installed on new school buses by the OEM. The Regulations specify that, when an infraction camera is installed on a school bus subject to the MVSA, the system must function without driver intervention and be positioned in a way that would allow the camera to capture vehicle licence plate information located at the rear of the passing vehicle, whether the vehicle is passing the school bus from the rear (i.e., a following vehicle) or the front (i.e., an oncoming vehicle) of the bus. The Regulations do not require the installation of infraction cameras, nor do they set requirements for specific data collection or processing.

The Regulations include a requirement that all new school buses subject to the MVSA will have to be equipped with a label indicating that the school bus may be equipped with an infraction camera system, regardless of whether an infraction camera is installed on the school bus. The presence of the label will aim to help increase the safety of the public by raising awareness with drivers of the potential risks passing a stopped school bus that is loading or unloading school-aged passengers.

Finally, the Regulations repeal subsection 15.1(1) and section 17 of the MVSR to align with the changes made to the MVSA in 2014.

At the time of prepublication in the Canada Gazette, Part I, the proposed Regulations included provisions that would have mandated an extended stop signal arm on school buses. Upon further review, and in consideration of stakeholder comments, these requirements were not included in the Regulations. Detailed information on this change is provided in the Consultation section below.

Regulatory development

Consultation

Transport Canada meets regularly with the federal authorities of other countries, as aligned regulations are central to trade and to a competitive Canadian automotive industry. For example, Transport Canada and the United States Department of Transportation hold semi-annual meetings to discuss issues of mutual importance and planned regulatory changes. Transport Canada also consults regularly with the automotive industry, public safety organizations, the provinces, and the territories.

Transport Canada informs the automotive industry, public safety organizations, and the general public when changes are planned to the MVSR. This notification is done, in part, through the publication of Transport Canada’s Forward Regulatory Plan, giving stakeholders advance notice of Transport Canada’s planned regulatory agenda and providing the opportunity to commence discussions on planned changes. The Regulations were included in Transport Canada’s Forward Regulatory Plan and were discussed at multiple meetings with stakeholders leading up to a formal consultation in a public notice (see the “Public notice” section below). The Regulations were also prepublished in the Canada Gazette, Part I (see “Prepublication in the Canada Gazette, Part I” section below), followed by a 75-day comment period.

Task Force on School Bus Safety

The Task Force on School Bus Safety brings together federal, provincial and territorial government representatives, safety associations, manufacturers and industry, school board representatives and school bus drivers to support a cohesive pan-Canadian approach to improving school bus safety. Since January 2019, the membership has met on a biweekly basis to share information and expertise on all aspects of school bus safety. Their work has been instrumental in developing the recommended safety measures that have been included in the Regulations. These efforts resulted in significant data collection and research to build an evidence base in support of a range of opportunities to strengthen school bus safety. This work also led to the development of the Strengthening School Bus Safety in Canada (PDF) report which was approved for publication by the Council of Ministers in February 2020.

Since the publication of the report in February 2020, both the Advisory Panel and the Steering Committee have continued their meetings in order to share information regarding ongoing pilot projects, research findings, consultation on regulatory development, as well as other school bus safety considerations, with the broader school bus safety community.

Public notice, Fall 2020

A public consultation titled Improving School Bus Safety in Canada, was posted on Transport Canada’s Let’s Talk Transportation online platform for comment from September 1, 2020, to October 7, 2020. The online consultation allowed stakeholders and members of the public to comment on the plan to require the recommended technologies on school buses. Motor vehicle safety stakeholders were contacted via email, and Transport Canada shared the consultation details via its social media platforms to solicit feedback from Canadians. Interested parties were invited to provide comments in a public discussion forum or to send more detailed submissions via email.

The online consultation indicated that Transport Canada intended to mandate the installation of all three technologies (i.e., perimeter visibility systems, extended stop signal arms, and infraction cameras) on Canadian school buses. A variety of stakeholders participated in the public consultation, including provincial governments and government organizations, transportation authorities, school districts, standards authorities, technical experts, consultants, Non-Governmental Organizations, and industry stakeholders, including school bus operators and manufacturers.

Stakeholders indicated broad support for any technology that could improve the safety of children on and around school buses. General concerns regarding the increased cost of school buses were brought up by a variety of stakeholders, in addition to the need for continued research and full regulatory analysis, including a cost-benefit analysis prior to mandating any new technologies on school buses. Some stakeholders also highlighted that increasing the cost of school buses by mandating new safety equipment could result in fewer buses being purchased and, consequently, more students using forms of transportation that are less safe.

Regarding infraction cameras, most comments supported their use but indicated that the technology is a punitive measure rather than a preventative one. Stakeholders expressed that infraction cameras are a part of a broader system of enforcement against the illegal passing of a school bus and that there are many aspects to such systems that go beyond the vehicle itself, including data storage, transfer and review, as well as privacy considerations surrounding the data captured by the system. Further to this, differences exist at the provincial level regarding school bus stopping laws and judicial procedures which would make a national specification regarding this technology difficult to develop. Ontario indicated that the implementation and use of infraction cameras are left to the discretion of municipalities. Quebec indicated that it had undertaken a review of infraction camera technology in the past and would not be in a position to utilize the technology if it were to be mandated on Canadian school buses as it would not undertake the complex legislative changes needed to do so. Quebec did, however, indicate that they would support a voluntary approach to regulating infraction cameras as this would allow individual jurisdictions to continue to assess for themselves if the technology would be beneficial for them.

Based on this feedback, Transport Canada concluded that the Regulations should not mandate the installation of infraction cameras; instead, the Regulations should prescribe specific safety requirements that will have to be met if infraction cameras are installed.

Comments regarding the extended stop signal arm were supportive of the technology as it was perceived to have the potential to increase the visibility of the stop signal for other motorists, therefore preventing dangerous passing incidents. Discussion around perimeter visibility systems was also generally supportive of the technology; however, some concern was raised regarding the potential for driver distraction from the display. To address these concerns, Transport Canada incorporated components of the Guidelines to Limit Distraction from Visual Displays in Vehicles under the proposed Document 111 for the display component of perimeter visibility systems.

Some stakeholders suggested that, as an alternative to regulation, information campaigns could be conducted to better educate drivers, cyclists, and pedestrians on how to safely behave around school buses. Transport Canada concluded that informational campaigns about rules of the road concerning school buses are a measure that could be taken by individual jurisdictions as appropriate in addition to the Regulations.

Detailed comments regarding mandating extended stop signal arms were generally supportive of the technology and increasing the conspicuity of the stop signal. However, stakeholders raised a potential issue with the use of the technology due to provincial traffic or vehicle width laws that may restrict the deployment of the extended stop signal arm. Other comments related to extended stop arms are discussed later in this section.

In addition to the comments on the technologies included in this regulatory proposal, stakeholders also suggested that Transport Canada review the current allowance in the MVSR for a four-lamp warning system for school buses to determine if such an allowance is still appropriate given that the eight-lamp warning system has been adopted in all United States jurisdictions and all jurisdictions in Canada with the exception of Ontario. Transport Canada determined it would consider this suggestion for a future proposal as additional consultations would be required.footnote 5

Prepublication in the Canada Gazette, Part I

The Regulations were prepublished in the Canada Gazette, Part I, on July 2, 2022, with a 75-day comment period. On the same day, Transport Canada informed motor vehicle safety stakeholders of the publication via email, which included a website link to the Canada Gazette publication, as well as corresponding draft copies of TSD 131 and Document 111 in both official languages. Transport Canada also shared the consultation details via its social media platforms. Interested parties were invited to provide comments via the Canada Gazette online comment system, by mail or email. Comments were received from 19 different stakeholders.

General comments

Stakeholders provided several general comments on the proposal related to cost, technology readiness, clarification of requirements, fleet operations, Transport Canada’s use of TSDs to address extended stop signal arm requirements and the proposed repealing of subsection 15.1(1) and section 17 of the MVSR.

Nine stakeholders commented on the incremental costs associated with the mandated technologies. Two provincial stakeholders requested additional financial support to account for the added costs, and eight stakeholders noted that, if bus acquisition budgets are not increased, some jurisdictions may need to reduce the number of buses purchased, which could lead to fewer bus routes and students needing to find alternative methods of transportation which have higher fatality and injury rates. Consequently, the Regulations could have a potential negative safety impact due to the increased cost of buses. Transport Canada acknowledges that additional costs could affect the acquisition of buses and that this will need to be considered in respective budget planning. While some jurisdictions have raised concerns, Transport Canada notes that other jurisdictions have already started fitting some of the equipment in question on buses. Mandating the technologies will effectively make this safety equipment available and, as noted by one stakeholder, its widespread installation could indeed lead to a decline in costs due to economies of scale. While the added costs may delay the purchase of new school buses with this safety equipment, the Regulations are expected to improve the safety of children around school buses.

Further evidence on the safety regarding the effectiveness of the extended stop signal arm and the perimeter visibility system was requested from 12 stakeholders. From the pilot projects, preliminary findings suggest that the extended stop arms, infraction cameras, and exterior visibility camera systems would have a positive impact on school bus safety; however, the sample size of vehicles used did not provide enough evidence to quantify the effectiveness of these technologies. As detailed in the baseline regulatory analysis scenario described in the cost benefit analysis section below, it is assumed that perimeter visibility systems would have similar effectiveness to back-up camera systems which would reduce accidents that involve school bus collisions with individuals by 30.5%.footnote 6 This assumption is made based on the average effectiveness rate of back-up camera systems, which ranges between 28% to 33%.footnote 7 The effectiveness analysis throughout all the stages of the development of these Regulations has utilized the most up-to-date available information as noted in the Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement (RIAS) published in the Canada Gazette, Part I. These analyses, which are included in the cost-benefit analysis (see Regulatory analysis — Benefits and costs), support the position that the perimeter visibility systems include the features necessary to improve the safety of children located in the vicinity of school buses; no additional information regarding the effectiveness of an extended stop signal arm was found in order to support requirements for this technology to be included in the Regulations at this time.

Two stakeholders suggested collaborating and aligning with the United States National Highway Traffic Safety Administration on the required safety technologies in the Regulations. Transport Canada agrees with the importance of North American cooperation and collaboration but notes that no equivalent requirements are present or being developed in the United States. Transport Canada believes that improving the safety of children around school buses justifies proceeding with its unique approach for Canada.

Eleven stakeholders expressed concern about the burden these Regulations may add to current operational challenges facing the school bus transportation industry. Three comments raised concerns about driver training and a shortage of bus drivers. nine comments raised concerns regarding differences in jurisdictional requirements (e.g., restrictions on the use of the stop signal arm and extended stop signal arm in some urban areas); four comments questioned whether a bus would need to be rendered out-of-service if there is a system malfunction. Three comments also indicated support for public awareness campaigns to inform motorists about the new systems and to remind them of the potential for children circulating around stopped school buses.

With respect to differences in jurisdictional requirements, the Regulations were written to be as broad as possible so that any technology installed in accordance with the Regulations may also be designed to respect the rules and regulations of each jurisdiction of operation.

Provincial and territorial governments are responsible for the establishment of regulations and enforcement strategies as they apply to vehicle and driver licensing, operation and maintenance of vehicles, as well as aftermarket components. Thus, individual jurisdictions have the authority to regulate the use of the safety equipment with which a school bus is equipped and set the criteria for determining what equipment malfunction would result in rendering a school bus out of service. The hiring of drivers and driver training are also addressed by each jurisdiction to meet their individual needs. That said, Transport Canada does not anticipate that the Regulations will require any additional driver training as they no longer include requirements with respect to extended stop signal arms, and the perimeter visibility systems will work automatically to display the necessary views to the driver. With regard to public education, most jurisdictions already have programs in place to address their respective needs in promoting school bus safety. As an example, jurisdictions that choose to have infraction cameras installed on their school buses could include information on this technology in their public awareness campaigns.

Prior to prepublication in the Canada Gazette, Part I, stakeholders did not provide any specific comments on implementation timelines. Following prepublication, five stakeholders representing school bus manufacturers, operators, and local jurisdictions indicated that the proposed coming into force date immediately upon publication would not provide sufficient time to develop, install and test equipment to meet the requirements. Stakeholders noted that the proposed nighttime visibility performance of perimeter visibility systems cannot be met with existing market-ready systems, and that, until the Regulations are published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, manufacturers will not start adjusting and modifying their manufacturing processes. Similarly, until school bus manufacturers start equipping their school buses with the technologies, local jurisdictions would not be in a position to start with driver or public education.

Following this stakeholder feedback, Transport Canada recognized that the technologies mandated by the Regulations will require revising the vehicle design and manufacturing processes to integrate the new safety equipment to function with the existing school bus controls and operating systems, and on a mass production scale, which had not been fully considered at prepublication in the Canada Gazette, Part I. It is therefore reasonable that manufacturers, in conjunction with their suppliers, will need additional time to design their vehicles and components, tender contracts, create the necessary tooling, test the components, and implement systems to ensure that the quality of their final products meets the needs of their customers. Similarly, provinces, territories, other jurisdictions, and school bus operators, will need extra time to plan for the added costs for the acquisition and maintenance of new buses fitted with the new safety features. As such, Transport Canada technical experts have determined that a three-year implementation timeline would be appropriate to allow manufacturers to comply with the Regulations.

Given the obstacles outlined, the Regulations now include transitional provisions that set the mandatory compliance date for the new requirements under CMVSS 111 and 131 in Schedule IV, Part II of the MVSR as November 1, 2027. This compliance date means that the Regulations will still come into force upon publication, so that manufacturers may comply with the new requirements immediately, if possible, while those that need more time to meet the requirements for perimeter visibility systems and infraction cameras (if installed), will have until November 1, 2027. While safety risks would not be fully addressed during the implementation period, Transport Canada concluded that it would not be practicable to set an earlier compliance date. Nevertheless, Transport Canada expects that the safety implications of this delay will be relatively small since the analysis already assumes that buses would be replaced gradually over a 10-year period only when existing buses have reached the end of their useful life (i.e., most buses are not expected to be replaced in the first three years following the publication of the Regulations), and manufacturers that are able to meet the requirements at any point during the implementation period may bring those technologies to market immediately without the need to wait for the mandatory compliance date. Transport Canada conducted follow-up consultations with affected stakeholders regarding the implementation of transitional provisions in the Regulations and confirmed their support for the three-year implementation period. Stakeholders did not raise further concerns about the implementation timeline.

With regard to the use of technical documents, one stakeholder expressed concern that the proposed modifications to TSD 131 would go beyond the permitted use of such documents. Transport Canada has assessed that the modifications to TSD 131 are technical elaborations on the substantive requirements in the Regulations and that, therefore, they fall within the authorities provided in the MVSA for a TSD.

With regard to repealing subsection 15.1(1) and section 17 of the MVSR, one stakeholder opposed removing the requirement for notification of a TSD modification through the publication of a notice in the Canada Gazette, Part I, indicating that the Canada Gazette is an industry-known source for information for such publications, and Internet subscribers receive automatic notifications of publication. However, with regard to notifications of publications, Transport Canada also sends out email notifications to all stakeholders whenever a revision to a TSD is published on its website, through a continuously updated email distribution list to which any stakeholder can request to be added. Stakeholders typically receive such notifications within one business day through this process. By contrast, it takes at least four weeks before a notification can be published on the Canada Gazette website. Faster notifications allow industry to react more quickly to TSD revisions. Also, by eliminating the need to publish a TSD notice in the Canada Gazette, Transport Canada will be able to effectively and quickly maintain alignment with safety-related changes in a source document (typically United States regulations) on which the TSD is based without compromising stakeholder engagement in the TSD update process.

On the subject of consultations, one stakeholder suggested that a publication of a notice on the Canada Gazette website would have been a more effective tool for seeking stakeholder feedback as opposed to utilizing the Let’s Talk Transportation platform on Transport Canada’s website. While both tools are available to seek public feedback, the Let’s Talk Transportation platform is the common tool that has been utilized by all modes of transportation at Transport Canada over the last several years. In addition to the platform being posted on the Transport Canada website, the Let’s Talk Transportation publication and request for comments was emailed to stakeholders, it was announced on social media, and Transport Canada also conducted multiple additional consultations including with industry, governments, school boards and others to seek stakeholder participation prior to the publication on the Let’s Talk Transportation platform.

Relative to the consultation process for TSD modifications, two stakeholders voiced concern as to the absence of formal prepublication consultations when adaptations are incorporated to the source document on which the TSDs are based, potentially leading to less effective consultations. In terms of such consultations, Transport Canada launched a new technical document update process in 2020 to address these concerns, including publishing a consultation page on its website explaining why a document is proposed to be modified and providing a copy of the proposed document with the changes highlighted. A link to this consultation page is sent to stakeholders via the email distribution list with a target consultation period of 45 days. All comments received are considered in the review process, and a final version of the TSD is published on the website and an email notification is sent to stakeholders. Compared to the prepublication process through the Canada Gazette, this new consultation process allows Transport Canada to react effectively and quickly to maintain alignment with safety-related changes in the source document on which the TSD is based (typically, United States regulations).

Cost benefit analysis

One stakeholder, representing approximately 600 businesses related to bus transportation, commented that the analysis did not consider cost impacts on smaller businesses that must purchase new school buses. As per TBS’s Policy on Cost-benefit Analysis and its Guide, a cost-benefit analysis primarily focuses on the direct impacts of a regulatory proposal. Therefore, the analysis thoroughly examined cost impacts on school bus manufacturers, who would bear the direct cost impacts of the Regulations, while acknowledging that such costs may ultimately be passed on to end users who would need to either purchase new school buses or provide school transportation services.

Eight stakeholders expressed concern that the cost of training school bus drivers to use the required technologies and maintaining the equipment was not included in the analysis. While maintenance costs have already been captured in the analysis, Transport Canada does not anticipate that school bus drivers would require additional training to use the required technology (see responses to General comments above for more detail).

Four stakeholders commented that the estimated costs were low and suggested that further study would be required. These comments were taken into consideration and Transport Canada conducted further research and analysis on the costs featured in the model. Based on Transport Canada’s additional research, the technology costs have been updated. With regard to the price of the perimeter visibility camera system, Transport Canada has reviewed the sourcefootnote 8 information and confirmed that the average price has gone down by approximately 13% since the prepublication of the proposed Regulations. Therefore, the analysis was revised to align with this new information (see Regulatory analysis for detail).

One stakeholder commented that the required technology may reduce mental strain and stress for school bus drivers. Transport Canada agrees with this comment and has elaborated on these benefits under the Regulatory analysis — Benefits and costs section located below.

Extended stop signal arm

Stakeholders submitted several comments expressing varying concerns with respect to the proposed mandate of extended stop signal arms, including considerations regarding

- the viewpoint from which the stop signal must be kept visible to oncoming motorists;

- the conditions for activation of the stop signal audible override warning;

- the timing for the full deployment of both the stop arms;

- data that would demonstrate operational performance in winter conditions and reliability of the technologies;

- performance requirements needing more clarity and precision, such as setting minimum and maximum acceptable lengths for the extended stop signal arm;

- potential variations in school bus design may undermine safety;

- the potential for the arm to block occupant emergency egress; and,

- the need for breakaway capability in the event the extended stop signal arm is struck by a passing vehicle.

Eleven stakeholders commented that alternative solutions to the extended stop signal arm should be assessed to help improve the safety of children through preventing motorists from passing stopped school buses when loading or unloading passengers, and the stakeholders needing additional time to do so. As potential safety alternatives, two stakeholders referenced a pedestrian audible warning system to alert crossing children to an oncoming vehicle, and several others suggested increasing the conspicuity of the stopped school bus with additional lights. Transport Canada assesses available technologies when beginning a regulatory proposal and proceeds based on available information at a given time. In this case, new technologies that may achieve the desired safety outcome have been highlighted by stakeholders as being potentially more beneficial, or as introducing fewer potentially unintended risks.

Additional consultations held between February and May 2024 allowed Transport Canada to better understand the issues brought forward by stakeholders and discussed above. Five stakeholders indicated that consistency is very important when it comes to signalling information to motorists, such as when they need to stop for a school bus. The implementation of extended stop signal arms on new school buses, but not on the existing fleet, could confuse motorists into thinking that they do not need to stop if the extended stop signal arm is not deployed. One stakeholder also indicated that specific procedures and driver training would be important so that drivers understand when they are required to deploy the extended stop signal arm and so that the drivers are not unnecessarily burdened by additional tasks when loading and unloading children at a stop. All stakeholders supported the continued assessment of safety technologies to achieve the desired safety outcome of protecting children outside the bus by increasing conspicuity of the school bus and preventing illegally passing vehicles, as demonstrated through the panel of experts on the CSA D250 technical committee.

Although removing the proposed requirement for extended stop signal arms from the Regulations would not immediately address the safety concern around the illegal passing of school buses, stakeholder feedback has highlighted the need to explore alternative solutions to extended stop signal arms. Transport Canada has worked with the CSA D250 school bus technical committee which has dedicated a specific conspicuity working group to continue working to assess technologies that could effectively improve safety for children outside the school bus by increasing the conspicuity of the school bus and preventing illegally passing vehicles.

Therefore, as a result of the stakeholder feedback, Transport Canada has decided not to move forward at this time with the requirements for extended stop signal arms that were prepublished in the Canada Gazette, Part I. Transport Canada will continue to work with technical experts from the CSA D250 school bus technical committee and its Motor Vehicle Investigation Teams to assess technologies that could achieve the desired safety outcome of reducing the risk of collisions associated with vehicles passing stopped school buses. Affected stakeholders have confirmed their support for removing the extended stop signal arm requirements from the Regulations and have indicated their commitment to working with Transport Canada to develop a practical and implementable alternative.

It should be noted that the Regulations do not prevent the installation or use of safety technologies, such as extended stop signal arms, on school buses. As such, any jurisdiction that wishes to pursue such an option, could still do so voluntarily.

In addition to the research and testing noted in the Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement (RIAS) published in the Canada Gazette, Part I, Transport Canada conducted several further tests of the technologies including the cold weather operational performance of an extended stop signal arm and the night visibility performance of perimeter visibility systems installed on a school bus, which are discussed below.

Perimeter visibility systems

Twelve stakeholders shared several comments related to the proposed perimeter visibility system requirements. Six stakeholders indicated that bus manufacturers were not prepared to meet the proposed requirements, with one stakeholder requesting further details including a justification for the dimensional requirements for the cylindrical test tool; clarifications about the defined visibility zone and performance requirements of the system in nighttime conditions; clarification about when the display must be activated and the required views to be provided; and questions about whether the system display must be stand-alone equipment or if it could be combined with another piece of equipment such as with a rear-view camera. Four stakeholders raised concerns regarding driver distraction and interaction with privacy laws, and one stakeholder expressed concern over a potential conflict with international documents, such as the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) document 16505:2019 —Road vehicles — Ergonomic and performance aspects of Camera Monitor Systems, and United Nations Regulation No. 46 (UN R46) — Uniform provisions concerning the approval of devices for indirect vision and of motor vehicles with regard to the installation of these devices.

The Regulations will require that the perimeter visibility system provide a video display to the bus driver of a cylindrical test tool within a defined visibility zone. Both the cylindrical test tool and the visibility zone have different specifications from those for assessing the visibility performance for the school bus mirrors in CMVSS 111. One stakeholder expressed concern that these differences will necessitate new technologies and additional testing but did not offer an alternative to the proposal. Given that this is a new requirement, it should be expected that additional testing will be required. Available perimeter visibility systems were tested by Transport Canada and no visibility issues with the defined zone were observed with existing technologies. While the visibility zone is slightly different from that for assessing school bus mirror performance, minimal effort would be required to adjust the perimeter of the visibility zone if testing for mirrors and perimeter visibility systems were to be conducted back-to-back. The Regulations specify a new cylindrical test tool representative of a 50th percentile 6-year-old child. Such a device could be fabricated by manufacturers at minimal expense with readily available primary construction materials from a local hardware store. As such, no changes were made to the Regulations in response to stakeholder comments about the cylindrical test tool.

With regard to visibility of the test cylinder under nighttime lighting conditions, several stakeholders, including four school bus manufacturers, expressed concerns that the current available technology for installation on school buses would not meet the visibility requirements under the proposed low lighting levels. However, stakeholders did not offer any information indicating what level of lighting would be possible, nor when such technology could be available for school buses. Further to the comments, Transport Canada conducted subsequent testing of two such systems, neither of which met the requirements as proposed with certainty. While the technology for night vision cameras exists, it is not yet marketed as available for school bus perimeter visibility systems. Given that existing systems are not designed for use at night, and their marginal performance in low-light conditions, Document 111 was revised such that the visibility requirement need only be met during daylight illumination conditions.

One stakeholder highlighted a need for clarification surrounding the views to be displayed, whereby the proposed regulatory text and draft Document 111 could be interpreted to require a view of the entire perimeter zone surrounding the school bus. To clarify, the intention of the requirement is to allow a view of the entire perimeter zone only if it meets the visibility requirements to the cylindrical text tool; the Regulations and Document 111 were revised accordingly.

Additionally, one stakeholder requested clarification regarding when the display needs to be operational. The proposed Regulations prepublished in the Canada Gazette, Part I, included a requirement that the display device must provide an image to the driver only when the school bus is stopped or travelling at a speed less than 15 km/h. This requirement could be interpreted to mean that an image is required even when the bus is parked without the engine operating. It was not the intention to have an image displayed when the vehicle is not in a mode to be driven. As such, the Regulations were revised to make it clear that an image is not required when the bus is stopped, and the vehicle’s propulsion system is switched “OFF.”

Images displayed on the perimeter visibility system are automatically selected based on the driver’s operation of the school bus, and the system must also include a mechanism that will provide the driver with the ability to toggle between cameras views. One stakeholder questioned if the intention was to provide the driver with access to toggle while the vehicle was in motion, indicating that it may be unsafe to interact with the display while the bus is moving. Transport Canada’s intention was to require the function when the vehicle is stationary. That said, manufacturers may allow access to toggle while the vehicle is in motion, based on their safety assessment of the installed system. The Regulations and Document 111 were revised to add this clarity.

With respect to some stakeholder comments, Transport Canada is of the opinion that the Regulations already address the concerns raised. For example, one stakeholder expressed that, without more specific requirements, manufacturers could use systems with only two cameras, and another stakeholder requested that the requirements should specify the necessary views, and names for the different views, to alleviate potential driver confusion. Transport Canada notes that the visibility zone defined in Document 111, which indicates the area around the perimeter of the bus where the cylindrical test tool must be visible, is clearly prescribed. Therefore, the method by which manufacturers choose to make this area visible to the driver (i.e., by how many cameras they use) does not affect the fact that the system must be designed to ensure that the cylindrical test tool is visible to the driver when it is in that delineated zone around the bus. Document 111 also specifies that an indicator must be present on the video display to identify the displayed view and that, at minimum, a left, right, forward and rearward view must be made available. Any number of cameras and views may be provided; therefore, the identification of the different views is left to the manufacturer.

In addition, one stakeholder questioned whether the video display of the perimeter visibility systems could be used for other functions or integrated with other equipment, such as a rear-view camera display. The Regulations do not prohibit other uses; however, the video display must, first and foremost, function under the conditions set out in the Regulations. If those conditions are not met because the display is being used for other purposes, then that system would be deemed non-compliant.

With regard to concerns about driver distraction, Transport Canada’s Guidelines to Limit Distraction from Visual Displays in Vehicles has been publicly available on the Transport Canada website since 2019. As noted in the RIAS at prepublication, and in response to comments to the September 2020 public notice on Transport Canada’s Let’s Talk Transportation online platform, components of the guidelines were incorporated in Document 111, including the display component of perimeter visibility systems. The perimeter visibility system is intended to increase situational awareness by focusing on risk areas during specific conditions of risk to school children. Furthermore, the display is used only at low speeds under 15 km/h and when stopped, where the risk of a VRU in a blind spot of a school bus is highest. While driver distraction cannot be completely eliminated, the application of these guidelines and the conditions that apply to when the display is used will help to mitigate potential distractions. No changes were made to the Regulations in response to the concerns about driver distraction.

Transport Canada reviewed the concern that privacy laws may prevent the use of cameras taking pictures or filming pedestrians without their consent. This concern was deemed a non-issue as the Regulations require the image be displayed, not recorded, and therefore, no such barrier is expected for the use of this equipment. In the case of a system that was designed with recording capability, the use of the system would need to comply with all applicable privacy laws within the local jurisdiction.

One stakeholder commented on the importance of having requirements that are aligned with existing international standards and regulations, in particular ISO 16505:2019 and UN R46. The stakeholder did not indicate if they thought the Regulations were incompatible or misaligned with international standards. Transport Canada conducted a thorough review and noted that both ISO and UN documents address the use of camera monitor systems as a replacement to outside rear-view mirrors; these documents do not apply to the use of perimeter visibility systems. As such, no incompatibility or conflict was noted between the Regulations and the ISO and UN documents. Hence, no changes were made to the Regulations in response to the concern raised about potential misalignment with international standards.

School bus manufacturers commented that some requirements were vague and lacked critical details, such as requiring that the video display be “usable by the driver” and that the toggle switch for selecting different views be located “within reach of the driver.” These stakeholders expressed a need for clear standards so that manufacturers will be able to determine if the equipment they install complies with the Regulations. The Regulations set the minimum requirements that must be achieved to reduce the risk of an incident. Although prescribing requirements for things such as the number of cameras required and location of a toggle switch for the perimeter visibility system may make demonstrating compliance to the Regulation more straight forward for a vehicle manufacturer, such prescriptions do not make a system more or less likely to achieve the desired safety outcome. How a safety outcome is achieved is up to the manufacturer to determine based on the system they are designing. Not all school bus manufacturers design their buses in the same way, and it would not be practicable for Transport Canada to prescribe how to implement the various components of a given technology. Permitting some leeway on how a safety outcome is achieved allows manufacturers (who know their vehicles best) to design accordingly and also provides manufacturers with the opportunity to develop innovative solutions without being hindered by prescriptive requirements. For example, a good camera system that stitches the images captured from all around the school bus without distorting the corners could eventually meet the requirements of the Regulations. Current camera systems with the capability of stitching images, however, distort those images quite a bit and are not able to meet the requirements of the Regulations. Over time, improvements made to this software could make it capable of satisfying requirements. For now, individual cameras may be used to provide the images of the perimeter of the school bus. The Regulations define minimum safety requirements but do not specify how those requirements are to be met, which will provide the flexibility for manufacturers to use or adapt new or developing technologies to meet requirements.

Infraction camera systems

Twelve stakeholders shared comments regarding proposed infraction camera and warning label requirements, including concerns that privacy laws may prevent the use of infraction cameras. These stakeholders highlighted the need to clarify the performance requirements for the infraction camera, as well as certain elements for the warning label (e.g., prescribing wording, size, location), and suggested that the warning label should only be mandatory when infraction cameras are installed.

As noted in the RIAS at prepublication, the Regulations do not mandate the installation of infraction camera systems. The Regulations are applicable only if such systems are fitted to the new vehicle by the original manufacturer before being sold. Infraction camera systems installed after the first point of sale are not subject to the Regulations.