Tang.ɢwan — ḥačxʷiqak — Tsig̱is Marine Protected Area Regulations: SOR/2024-122

Canada Gazette, Part II, Volume 158, Number 13

Registration

SOR/2024-122 June 10, 2024

OCEANS ACT

P.C. 2024-655 June 10, 2024

Her Excellency the Governor General in Council, on the recommendation of the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans, makes the annexed Tang.ɢwan — ḥačxʷiqak — Tsig̱is Marine Protected Area Regulations under subsection 35(3)footnote a of the Oceans Act footnote b.

Tang.ɢwan — ḥačxʷiqak — Tsig̱is Marine Protected Area Regulations

Interpretation

Definition of Marine Protected Area

1 (1) In these Regulations, Marine Protected Area means the area of the sea that is designated by section 2.

Geographical coordinates

(2) In the schedule, all geographical coordinates (latitude and longitude) are expressed in the North American Datum 1983, Canadian Spatial Reference System (NAD83, CSRS).

Geographical coordinates for points

(3) The geographical coordinates of the points referred to in sections 2 and 3 are set out in the schedule.

Designation

Marine Protected Area

2 (1) The area of the sea depicted in the schedule that is bounded by the following lines is designated as the Tang.ɢwan — ḥačxʷiqak — Tsigis Marine Protected Area:

- (a) a rhumb line drawn from point 1 to point 2, with point 2 being located on the western boundary of the Scott Islands Protected Marine Area, as described in Schedule 1 to the Scott Islands Protected Marine Area Establishment Order;

- (b) a rhumb line drawn southerly following the western boundary of the Scott Islands Protected Marine Area, as described in Schedule 1 to the Scott Islands Protected Marine Area Establishment Order, to point 3;

- (c) a rhumb line southeasterly following the boundary of the Scott Islands Protected Marine Area, as described in Schedule 1 to the Scott Islands Protected Marine Area Establishment Order, to point 4;

- (d) a series of rhumb lines drawn from point 4 to point 5 and then to point 6;

- (e) a rhumb line to a point on the international boundary between Canada and the United States intersecting a rhumb line drawn from point 6 to point 7;

- (f) a line southwesterly following the international boundary between Canada and the United States to point 8, on the seaward limit of the exclusive economic zone of Canada; and

- (g) a line northwesterly following the seaward limit of the exclusive economic zone of Canada to a point intersecting a rhumb line drawn from point 1 to point 9, and then a rhumb line back to point 1.

Seabed, subsoil and water column

(2) The Marine Protected Area consists of the seabed, the subsoil to a depth of 1 000 m and the water column above the seabed.

Management Zones

Boundaries

3 The Marine Protected Area consists of the following management zones, each of which is depicted in the schedule:

- (a) the Dellwood Zone, which consists of the seabed, the subsoil to a depth of 1 000 m and the water column above the seabed and is bounded by a series of rhumb lines drawn from points 10 to 13 and then back to point 10;

- (b) the Union Zone, which consists of the seabed, the subsoil to a depth of 1 000 m and the water column above the seabed and is bounded by a series of rhumb lines drawn from points 14 to 17 and then back to point 14; and

- (c) the General Zone, which consists of the seabed, the subsoil to a depth of 1 000 m and the water column above the seabed that is within the part of the Marine Protected Area that is not within the Dellwood Zone or the Union Zone.

Prohibited Activities

Prohibition

4 It is prohibited to carry out any activity in the Marine Protected Area that disturbs, damages, destroys or removes from the Marine Protected Area any living marine organism or any part of its habitat or that is likely to do so.

Exceptions

Permitted activities

5 Despite section 4, the following activities may be carried out in the Marine Protected Area:

- (a) the following fishing activities when conducted in accordance with the Fisheries Act, the Coastal Fisheries Protection Act and the regulations to those Acts:

- (i) fishing, other than commercial fishing, that is authorized under the Aboriginal Communal Fishing Licences Regulations and that does not involve the use of fishing gear that contacts the seabed, such as bottom trawls, dredges, traps or bottom longlines;

- (ii) commercial or recreational fishing in the General Zone carried out by means of a pelagic hook and line or a midwater trawl that does not involve the use of that fishing gear at a depth greater than 500 m below the sea surface, and

- (iii) commercial or recreational fishing in the Dellwood Zone or the Union Zone that is carried out by means of a pelagic hook and line that does not involve the use of that fishing gear at a depth greater than 100 m below the sea surface;

- (b) the laying, maintenance or repair of cables;

- (c) the navigation of a vessel;

- (d) an activity that is carried out for the purpose of public safety, national defence, national security or law enforcement or to respond to an emergency; and

- (e) an activity that is part of an activity plan that has been approved by the Minister.

Activity Plan

Submission to Minister

6 A person who proposes to carry out a scientific research or monitoring activity or an educational activity in the Marine Protected Area must submit to the Minister an activity plan that contains the following information:

- (a) the person’s name, address, telephone number and email address;

- (b) if the activity plan is submitted by an institution or organization, the name of the individual who will be responsible for the proposed activity and their title, address, telephone number and email address;

- (c) the name of each vessel that the person proposes to use to carry out the activity, its state of registration and registration number, its radio call sign and the name, address, telephone number and email address of its owner, master and any operator;

- (d) a detailed description of the proposed activity and its purpose, the methods or techniques that are to be used to carry out the activity and the data to be collected;

- (e) the geographical coordinates of the site of the proposed activity and a map that shows the location of the activity within the Marine Protected Area;

- (f) the proposed dates and alternative dates on which the proposed activity is to be carried out;

- (g) a list of the equipment that is to be used, the means by which it will be deployed and retrieved and the methods by which it is to be anchored or moored;

- (h) a list of the types and quantities of samples that are to be collected;

- (i) a list of any substances that may be deposited during the proposed activity in the Marine Protected Area — other than substances that are authorized under the Canada Shipping Act, 2001 to be deposited in the navigation of a vessel — and the quantity and concentration of each substance;

- (j) a description of the adverse environmental effects that are likely to result from carrying out the proposed activity and of any measures that are to be taken to monitor, avoid, minimize or mitigate those effects;

- (k) a description of any scientific research or monitoring activity or educational activity that the person has carried out or anticipates carrying out in the Marine Protected Area; and

- (l) a general description of any study, report or other work that is anticipated to result from the proposed activity and its anticipated date of completion.

Approval

7 (1) The Minister must approve an activity plan if

- (a) the scientific research or monitoring activities set out in the plan are not likely to destroy the habitat of any living marine organism in the Marine Protected Area and

- (i) will serve to increase knowledge of the habitat of any living marine organism in the Marine Protected Area or the ecosystems these habitats support in the Marine Protected Area, or

- (ii) will serve to assist in the management of the Marine Protected Area; and

- (b) the educational activities set in out in the plan

- (i) are not likely to damage, destroy or remove from the Marine Protected Area any living marine organism or any part of its habitat, and

- (ii) will serve to increase public awareness of the Marine Protected Area; or

- (c) the approval of the activity plan is necessary to be consistent with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, signed by Canada on December 10, 1982 or customary international law.

Approval prohibited

(2) However, the Minister must not approve an activity plan under paragraph 1(a) or (b) if

- (a) the scientific research or monitoring activities set out in the plan are likely to adversely affect the ecological integrity of

- (i) the Salty Dawg hydrothermal vent, being the area of the sea depicted in the schedule that is bounded by a series of rhumb lines drawn from points A to D and then back to point A, or

- (ii) the High Rise hydrothermal vent, being the area of the sea depicted in the schedule that is bounded by a series of rhumb lines drawn from point E to H and then back to point E;

- (b) any substance that may be deposited during the proposed activity is a deleterious substance as defined in subsection 34(1) of the Fisheries Act, unless the deposit of the substance is authorized under subsection 36(4) of that Act; or

- (c) the cumulative environmental effects of the proposed activity, in combination with those of any other past and current activities carried out in the Marine Protected Area, are such that the activity is likely to

- (i) destroy the habitat of any living marine organism in the Marine Protected Area, or

- (ii) adversely affect the biological, chemical or oceanographic processes that maintain or enhance the biodiversity, structural habitat or ecosystem function in the Marine Protected Area.

Timeline for approval

(3) The Minister’s decision in respect of an activity plan must be made within

- (a) 90 days after the day on which the plan is received; or

- (b) if amendments to the plan are made, 90 days after the day on which the amended plan is received.

Activity report

8 (1) If the Minister approves an activity plan, the person who submitted it must provide the Minister with an activity report within 90 days after the last day of the activity and the report must contain

- (a) the data collected during the activity;

- (b) the type and quantity of any sample that was collected, the date of collection and the geographic coordinates of the sampling site;

- (c) an evaluation of the effectiveness of any measures taken to monitor, avoid, minimize or mitigate the adverse environmental effects of the activity; and

- (d) a description of any event that occurred during the activity and that was not anticipated in the activity plan, if the event could result in the disturbance, damage, destruction or removal from the Marine Protected Area of any living marine organism or any part of its habitat.

Studies, reports or other publications

(2) The person must also provide the Minister with a copy of any study, report or other publication that results from the activity and is related to the conservation and protection of the Marine Protected Area. The study, report or other publication must be provided within 90 days after the day on which it is published.

Repeal

9 The Endeavour Hydrothermal Vents Marine Protected Area Regulations footnote 1 are repealed.

Coming into Force

Registration

10 These Regulations come into force on the day on which they are registered.

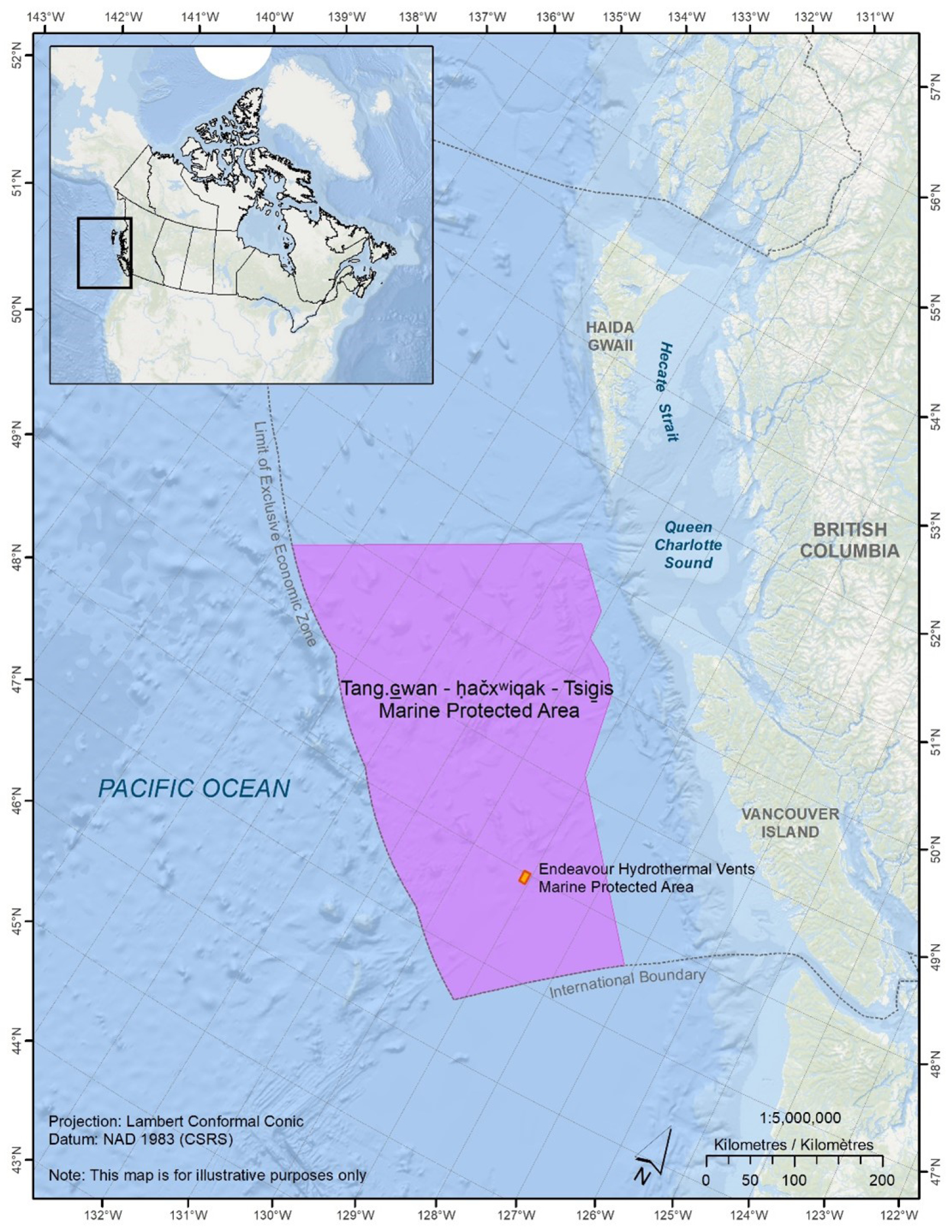

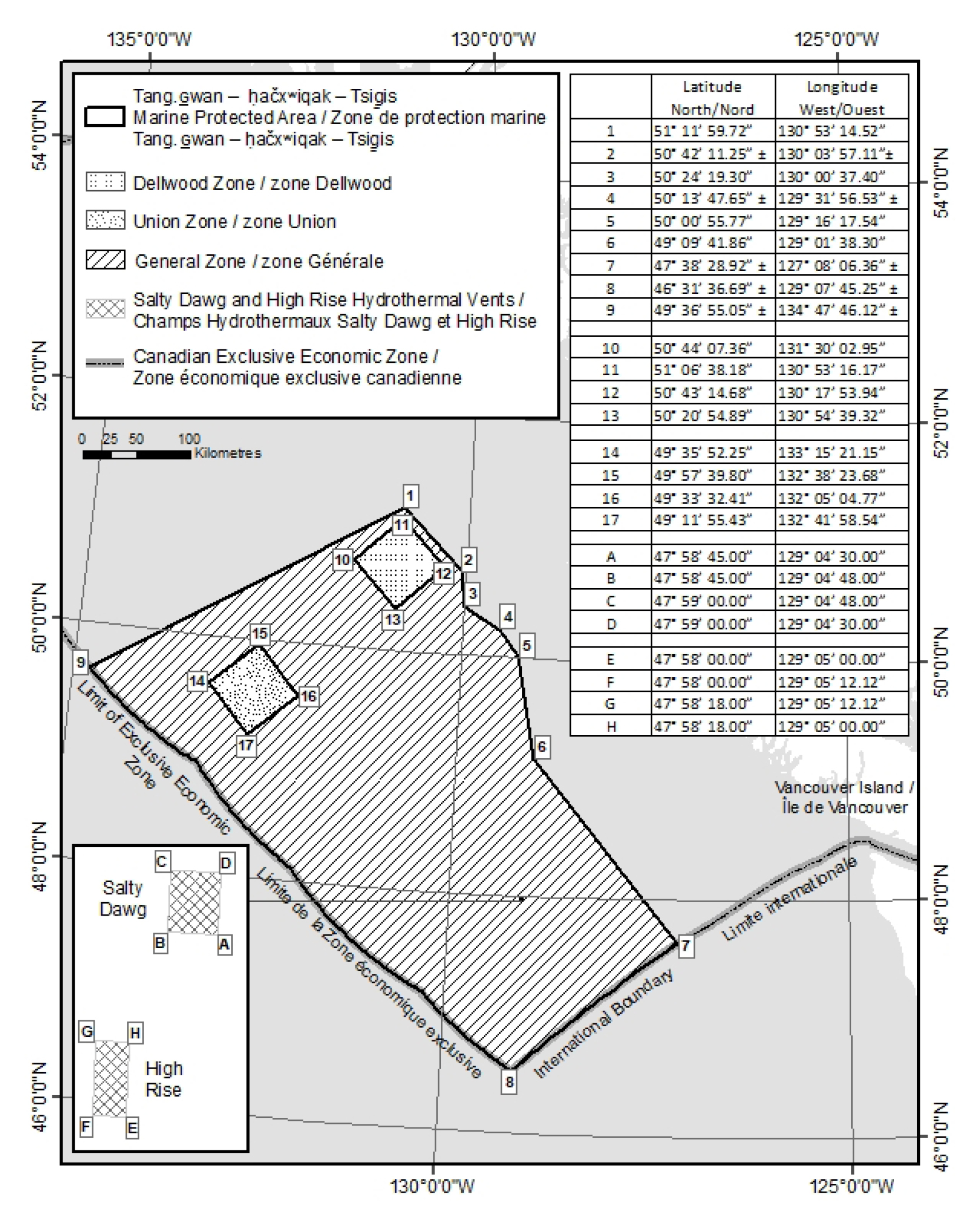

SCHEDULE/ANNEXE

(Subsections 1(2) and (3) and 2(1), section 3, subparagraphs 7(2)(a)(i) and (ii)/paragraphes 1(2) et (3) et 2(1), article 3 et sous-alinéas 7(2)(a)(i) et (ii))

Tang.ɢwan — ḥačxʷiqak — Tsigis Marine Protected Area/Zone de protection marine Tang.ɢwan — ḥačxʷiqak — Tsigis

REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS STATEMENT

(This statement is not part of the Regulations.)

Executive summary

Issues: Seamounts and hydrothermal vents have been identified as ecologically or biologically significant areas (EBSAs) domestically, and as vulnerable marine ecosystems internationally. These areas provide important habitats for commercial and non-commercial species in the area. Risk analyses have shown that some ongoing and potential future activities pose risks to the seamounts and hydrothermal vent ecosystems in the Offshore Pacific Bioregion in Canada’s Exclusive Economic Zone of the Pacific Ocean. Designating a marine protected area (MPA) under the Oceans Act in the area provides a regulatory mechanism to conserve and protect the area and the natural resources it supports.

Description: The Tang.ɢwan — ḥačxʷiqak — Tsig̱is Marine Protected Area Regulations (the Regulations) designate an approximately 133 017 km2 area in the Offshore Pacific Bioregion as an MPA, the Tang.ɢwan – ḥačxʷiqak – Tsig̱is MPA.footnote 2 Zoning is used to provide varying levels of protection within the MPA, offering more stringent protection to areas that need it most. The Regulations establish a general prohibition against activities likely to disturb, damage, destroy, or remove any living marine organism or any part of its habitat from the MPA. They also identify specific exceptions to the general prohibition allowing activities that are compatible with the conservation objective of the MPA, which is to conserve, protect and enhance understanding of unique seafloor features, including seamounts and hydrothermal vents, and the marine ecosystems they support in the MPA. For example, vessel traffic, and pelagic hook and line fishing near the ocean’s surface, will be allowed to continue in the MPA. Conversely, fishing using bottom contact gear, mining, and oil and gas development are not permitted in the MPA. Scientific research, scientific monitoring, and educational activities are allowed within the MPA if the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans approves the Activity Plan.

The Regulations provide long-term, comprehensive protection to this ecologically and biologically significant area and provide for the proper management of activities that would otherwise adversely impact the ecologically significant components of the area.

Rationale: The designation of the MPA brings comprehensive regulatory protection to approximately 2.3% of Canada’s ocean territory. It directly contributes to the Government of Canada’s goals to conserve 25% of Canada’s oceans by 2025, and 30% by 2030, by adding 0.88% to Canada’s marine conservation targets (MCT). The incremental addition to Canada’s MCT is 0.88% rather than 2.3% because the MPA encompasses a marine refuge established in 2017 that contributed 1.44% to Canada’s MCT. When compared to the marine refuge’s closure of bottom contact fisheries, the MPA offers enhanced protection to the area.

Consultation occurred over more than a three-year period. General support for the MPA’s design and measures was achieved through the consultation process. The design and regulatory approach for the MPA considered the advice received through consultation and considered both conservation needs and economic opportunities for fishers. During consultations, certain First Nations expressed an interest in collaboratively managing the MPA; Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) and the interested First Nations have signed a Memorandum of Understanding to support this approach.

The incremental costs for industry associated with the Regulations are estimated to be negligible, as most fishing industry adjustments and costs were borne following a 2017 prohibition on bottom contact commercial and recreational fishing activities in the area (i.e. the marine refuge established in 2017). Tuna, the most lucrative fishery in the area, is not affected since it does not undermine the conservation objective of the MPA. Midwater trawl fishing is allowed to continue throughout most of the area under the Regulations; however, some monitoring and compliance costs to confirm that the gear does not fall below allowable depths may be incurred. Government costs are estimated to be just under $4.0 million (2023$) in present value over ten years for cooperative management, research, and enforcement, drawn from existing funding.

The Regulations provide protection against general or unanticipated threats, a greater degree of certainty of long-term protection, and increased enforcement capabilities. Due to the higher level of enforceability associated with regulations, some benefits are anticipated from indirect and non-use value of the EBSAs, stemming from their role within the ecosystem and the services they provide, as well as the existence of the EBSAs themselves both for their own benefit and for altruistic or bequest purposes.

Issues

The Government of Canada recognizes the need to preserve the health and productivity of our oceans. In the 2019 mandate letters issued by the Prime Minister to the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard and the Minister of Environment and Climate Change, one of the identified priorities was to work towards conserving 25% of Canada’s oceans by 2025. This priority was echoed in the 2020 Speech from the Throne and 2021 mandate letters. The designation of marine protected areas (MPAs) under the Oceans Act provides for the protection of marine ecosystems from human-induced pressures and helps promote the long-term health and sustainability of our fisheries and oceans.

In 2017, an area of the Pacific Ocean, the Offshore Pacific Area of Interest, was identified as a candidate for designation as an Oceans Act MPA. The area, located on average 150 km from the coast of Vancouver Island in Canada’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), encompasses seamounts and hydrothermal vents, features identified as ecologically or biologically significant areas (EBSAs) domestically, and as vulnerable marine ecosystems (VMEs) internationally. The results of two independent qualitative risk analyses determined that certain current and potential future activities in the area, particularly those that make contact or have the potential to make contact with the seafloor, posed a risk to the conservation of the area and the natural resources it supports. Additional governmental intervention was considered necessary for the responsible management of activities within the area, to help conserve and protect the benthic (seafloor) ecosystems associated with the seamounts and hydrothermal vents in the long-term.

Following the Canada Gazette, Part I, public comment period on the proposed MPA regulations from February 18 to March 20, 2023, the Tang.ɢwan — ḥačxʷiqak — Tsig̱is Marine Protected Area Regulations (the Regulations) designate the Tang.ɢwan — ḥačxʷiqak — Tsig̱is MPA (the ThT MPA or the MPA).

Background

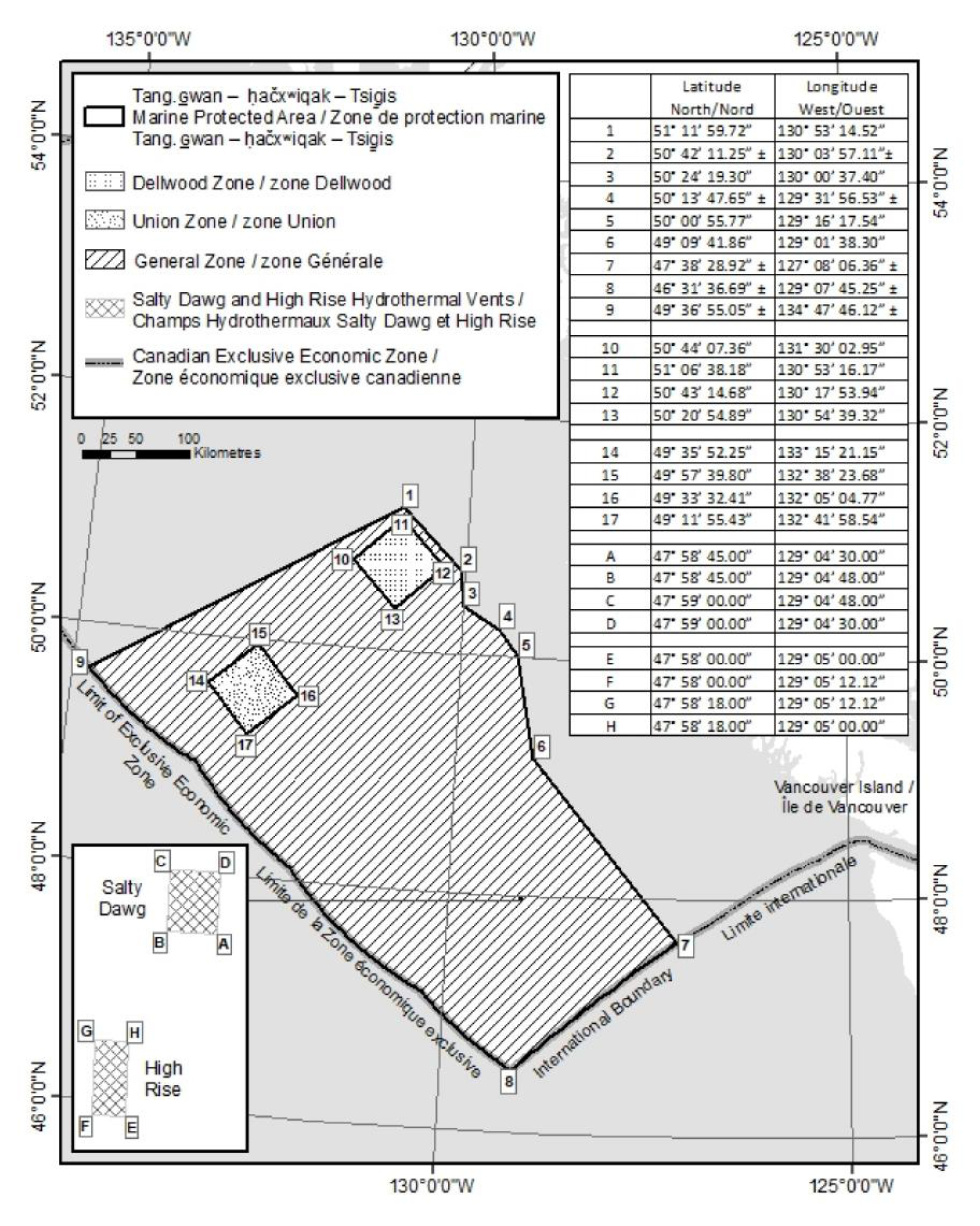

Located in the southern portion of the Offshore Pacific Bioregion, the 133 017 km2 ThT MPA extends from the toe of the continental slope westward to the boundary of Canada’s EEZ and southward to the Canada–United States border (Figure 1).footnote 3 It contains the majority of seamounts and all known hydrothermal vents under Canada’s authority. Both seamounts and hydrothermal vents are rare and unique geological features associated with the spreading of tectonic plates, and are “biological hotspots” for deep-water species.footnote 4

Seamounts provide stable hard substratum on which corals, sponges, and other species settle and grow. These living structures provide a broad range of ecosystem functions, including substrates for attachment, shelter and feeding, and generally support higher levels of biodiversity and productivity than surrounding habitats. Twelve new-to-science coral and sponge species have been recently identified within the MPA. Seamounts support productive and diverse ecosystems within the MPA, and provide important habitats for commercially important species (e.g. Pacific halibut, sablefish and others) and many species of conservation concern (e.g. bocaccio, canary, yellowmouth, rougheye and yelloweye rockfish species, marine mammals, sea birds, and others). Forty-seven of the 65 known or predicted seamounts in the Offshore Pacific Bioregion are located within the ThT MPA.

Hydrothermal vents in the MPA are noted for exceptionally diverse microbial communities, and are areas of increased resource availability and habitat diversity, which are able to support unique assemblages of vent organisms and transfer energy to adjacent non-vent habitats. Habitat features of the northeast Pacific hydrothermal vents include sulphide structures, unsedimented basalts, sedimented basalts, the hydrothermal plume, and the sub-seafloor hydrothermal fluid cells, with their associated communities of microorganisms that contribute to primary productivity. Each of these habitat features hosts distinct animal communities specialized to the local conditions and found nowhere else in the world. For example, the Endeavour hydrothermal vents, one of the 18 known venting areas in the MPA, are home to 10 species recorded nowhere else in the world. Middle Valley, another vent field in the MPA, also hosts species not recorded elsewhere. One hundred per cent of known hydrothermal vents in Canada are located within the ThT MPA.

Figure 1: Location of the Tang.ɢwan — ḥačxʷiqak — Tsig̱is Marine Protected Area.

Figure 1: Location of the Tang.ɢwan — ḥačxʷiqak — Tsig̱is Marine Protected Area - Text version

Figure one is a map of the location of the Tang.ɢwan - ḥačxwiqak - Tsig̱is Marine Protected Area. At the top left of the figure is a bigger scale map which shows the location of the figure one map within Canada. The figure one map encompasses the north west tip of Washington State in the United States and extends up the western edge of British Columbia in Canada, up to the south west corner of Alaska. The International Boundaries between Canada and the United States as well as the Limit of the Exclusive Economic Zone of Canada are shown in a dotted line. Vancouver Island and Haida Gwaii are both identified, as is the Pacific Ocean, Queen Charlotte Sound and Hecate Strait. The boundaries of the Tang.ɢwan - ḥačxwiqak - Tsig̱is Marine Protected Area, located in the offshore Pacific Ocean, West of Vancouver Island, is depicted on the map. The Endeavour Hydrothermal Vents Marine Protected Area is depicted within the Tang.ɢwan - ḥačxwiqak - Tsig̱is MPA. The latitudes and longitudes skirt the edge of the map. The scale and north arrow appear on the lower right corner of the map. In the lower left corner is the projection, which is Lambert Conformal Conic, and datum, which is NAD 1983 (CSRS). Also in the lower left corner is a note which states “This map is for illustrative purpose only.”

Human activities

Prior to the designation of the MPA, the main human uses within the area were marine transportation, scientific research (e.g. volcanology, fish stock surveys) and commercial fishing.

Marine transportation is the most prevalent human activity in the area and can be described as mainly large cargo vessels involved in international shipping transiting the area along specific routes.

The MPA’s distance from shore has historically limited fishing activities. The Pacific Albacore tuna commercial fishery is the most valuable fishery occurring in the MPA, occurring within 1.5 m of the ocean’s surface. A few midwater trawl fishing activities within the bounds of the MPA were recorded in Canadian fishers’ logbooks prior to MPA designation; although, no midwater trawl fishing had been recorded around the Union or Dellwood seamounts. Midwater trawl gear is regularly deployed at depths above 500 m from the sea surface, but has been known to interact with the seafloor at depths greater than 500 m.

Commercial and recreational groundfish fishing on the seamounts and in the hydrothermal vents area has been closed since late 2017. A set of variation orders (FN 1241) under the Fisheries Act was implemented to protect the seamounts and hydrothermal vents from impacts associated with bottom contact fishing gear used in the halibut, sablefish, rockfish, lingcod and dogfish fisheries. There were no records indicating recreational fishing for groundfish or other species had occurred in the area.

First Nations have indicated that the area has cultural importance, and their fishers visit and fish the area, and historically fished the area for traditional use and commercial purposes. While Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) records reflect minimal to no historic use by First Nations for food, social and ceremonial (FSC) fishing, two records of recent First Nations’ FSC fishing exist. These were recorded as dual fishing activities, where FSC groundfish fishing occurred during commercial groundfish fishing trips that took place partially in the area now designated as an MPA.

Cable laying has occurred in the boundaries of the MPA for both communications and scientific research. Five international telecommunication cables lay within the MPA, transecting the area north to south, and east to west, generally across flat surfaces. The University of Victoria’s Ocean Networks Canada maintains NEPTUNE, an underwater deep sea cabled observatory, with a length of 840 km from Vancouver Island across the continental shelf into the MPA. This observatory provides valuable information regarding oceanographic conditions and provides a warning system for the tracking of tsunamis on Canada’s Pacific Coast.

No active oil and gas exploration, significant discovery, or production licences have been issued for areas within the MPA. According to a resource assessment produced by Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), there is very low to no potential for conventional petroleum resources in the MPA. There are areas of high potential for gas hydrates; however, this potential was constrained due to technological and economic factors. Given the current federal BC offshore oil and gas moratorium, an oil and/or natural gas project would not have been considered within or near the MPA even before its designation.

In addition, the NRCan resource assessment indicated that, within the MPA, there is potential for deep-sea mining exploration and development (e.g. mining for volcanogenic massive sulphides, ferromanganese and manganese crusts, and manganese nodules), as well as other geological resources such as geothermal energy and carbon sequestration reservoirs. However, deep-sea mining, energy production, and carbon capture and storage have not occurred in the area and were not anticipated in the near future even in the absence of MPA designation. In the case of deep-sea mining, the lack of a regulatory framework for this in Canada (including the absence of a regime for granting mineral tenure) had been an impediment to this occurring. Consistent with this, the federal government announced in February 2023 that, in the absence of a rigorous regulatory structure, Canada would not authorize seabed mining in areas under its jurisdiction. It was also determined that unconventional (e.g. offshore wind and wave) energy generation was unlikely to be located within the boundary of the MPA in the near term given the distance from shore.

Objective

The objective of the Regulations is to establish the ThT MPA under the Oceans Act and facilitate the achievement of the conservation objective for the MPA: to conserve, protect and enhance understanding of unique seafloor features, including seamounts and hydrothermal vents, and the marine ecosystems they support in the MPA.

Description

The Regulations, made under the authority of subsection 35(3) of the Oceans Act, designate the ThT MPA to provide proactive, long-term, comprehensive protection to this ecologically and biologically significant area and provide for the proper management of activities that would otherwise adversely impact the ecologically significant components of the area.

The Regulations

- establish the boundaries of the ThT MPA, including the zoning approach;

- set out a general prohibition, prohibiting activities that disturb, damage, destroy, or remove from the MPA any living marine organism or any part of its habitat, or that are likely to do so;

- identify specific exceptions to the general prohibition to allow certain activities that do not compromise the conservation objective identified for the MPA;

- define the criteria for ministerial approval of Activity Plans authorizing scientific research and monitoring, and educational activities in the MPA; and,

- repeal the Endeavour Hydrothermal Vents Marine Protected Area Regulations (SOR/2003-87) upon the designation of the ThT MPA.

The boundary of the ThT MPA encompasses approximately 133 017 km2 and includes the water column, the seabed, and the subsoil to a depth of 1 000 m. The Regulations establish three management zones, providing varying levels of protection within the MPA to offer more stringent protection to the areas that need it most. To protect the more sensitive Union and Dellwood seamounts and the habitats and species they support, each seamount has its own management zone that is approximately 3 600 km2 in size, called the Union Zone and the Dellwood Zone, respectively. The remaining area of the MPA, not covered by the Union and Dellwood Zones, is the General Zone, an area approximately 125 817 km2 in size (Figure 2).

Figure 2: MPA boundary with geographic coordinates and zoning approach.

Figure 2: MPA boundary with geographic coordinates and zoning approach - Text version

The schedule depicts a map of the Tang.ɢ̱wan — ḥačxʷiqak —Tsig̱is Marine Protected Area as an area of the sea in the exclusive economic zone of Canada west of British Columbia. The boundary of the marine protected area is depicted by a series of lines connecting points 1 to 9 as follows: a rhumb line commencing at point 1 at 51°11´59.72ʺ N, 130°53´14.52ʺ W to point 2 to at approximately 50°42´11.25ʺ N, 130°03´57.11ʺ W, then a rhumb line to point 3 at 50°24´19.30ʺ N, 130°00´37.40ʺW, then a rhumb line to point 4 at approximately 50°13´47.65ʺN, 129°31´56.53ʺ W, then a rhumb line to point 5 at 50°00´55.77ʺ N, 129°16´17.54ʺ W, then a rhumb line to point 6 at 49°09´41.86ʺ N, 129°01´38.30ʺ W, then a rhumb line to point 7 at approximately 47°38´28.92ʺ N, 127°08´06.36ʺ W, then following the International Boundary line between Canada and the United States to point 8 at approximately 46°31´36.69ʺ N, 129°07´45.25ʺ W, then following the Exclusive Economic Zone limit line to point 9 at approximately 49°36´55.05ʺ N, 134°47´46.12ʺ W, then a rhumb line back to point 1. The boundary of the marine protected area is also the boundary of the general zone. The Dellwood Zone is depicted as a zone within the boundary of the marine protected area and is depicted by a series of rhumb lines connected at points 10 to 13 as follows: a rhumb line commencing at point 10 at 50°44´07.36ʺ N, 131°30´02.95ʺ W to point 11 at 51°06´38.18ʺ N, 130°53´16.17ʺ W, then a rhumb line to point 12 at 50°43´14.68ʺ N, 130°17´53.94ʺ W, then a rhumb line to point 13 at 50°20´54.89ʺ N, 130°54´39.32ʺ W, then a rhumb line back to point 10. The Union Zone is depicted as a zone within the boundary of the marine protected area and is depicted by a series of rhumb lines connected at points 14 to 17 as follows: a rhumb line commencing at point 14 at 49°35´52.25ʺ N, 133°15´21.15ʺ W to point 15 at 49°57´39.80ʺ N, 132°38´23.68ʺ W, then a rhumb line to point 16 at 49°33´32.41ʺ N, 132°05´04.77ʺ W, then a rhumb line to point 17 at 49°11´55.43ʺ N, 132°41´58.54ʺ W, then a rhumb line back to point 14. The boundary of the Salty Dawg hydrothermal vents is depicted by a series of rhumb lines connecting points A to D as follows: a rhumb line commencing at point A at 47°58´45.00ʺ N, 129°04´30.00ʺ W to point B at 47°58´45.00ʺ N, 129°04´48.00ʺ W, then a rhumb line to point C at 47°59´00.00ʺ N, 129°04´48.00ʺ W, then a rhumb line to point D at 47°59´00.00.ʺ N, 129°04´30.00ʺ W, then a rhumb line back to point A. The boundary of the High Rise hydrothermal vents is depicted by a series of rhumb lines connecting points E to H as follows: a rhumb line commencing at point E at 47°58´00.00ʺ N, 129°05´00.00ʺ W to point F at 47°58´00.00ʺ N, 129°05´12.12ʺ W, then a rhumb line to point G at 47°58´18.00ʺ N, 129°05´12.12ʺ W, then a rhumb line to point H at 47°58´18.00.ʺ N, 129°05´00.00ʺ W, then a rhumb line back to point E.

As previously mentioned, the Regulations establish a general prohibition against activities that disturb, damage, destroy, or remove from the MPA any living marine organism or any part of its habitat, or that are likely to do so. The Regulations also identify exceptions to the general prohibition to allow certain activities that do not compromise the MPA’s conservation objective. The Regulations do not specify exceptions for oil and gas exploration, development and production, mining exploration and exploitation, fishing with bottom trawl gear or other industrial activities subject to Canada’s MPA Protection Standard.footnote 5 This means that, in effect, the general prohibition prohibits said industrial activities because they are known to have the prohibited effects.

The Regulations identify the following exceptions to the general prohibition:

- Safety and security: Activities related to public safety, national defence, national security, law enforcement, or in response to an emergency (including environmental emergencies) continue to be allowed throughout the MPA.

- Vessel traffic: Vessel traffic continues to be allowed throughout the MPA.

- Fishing: First Nations FSC fishing is allowed within all zones of the MPA, provided that bottom contact fishing gear is not utilized. Commercial and recreational fishing using pelagic hook and line gear is allowed in all three of the MPA’s zones, provided the gear does not go below a depth of 100 m from the sea surface in the Union or Dellwood Zones, or 500 m from the sea surface in the General Zone. Midwater trawl is allowed in the General Zone, provided the gear does not go below a depth of 500 m from the sea surface. To help verify compliance with this midwater trawl depth restriction, DFO plans to require vessels fishing in the General Zone to monitor the depths of their midwater trawl gear. This will be implemented by the addition of conditions to fishing licences issued under the Fisheries Act and the Coastal Fisheries Protection Act. Refer to Table 1 for a summary of the fishing activities allowed in each zone.

- Cables: The laying, maintenance and repair of submarine cables are allowed within the MPA and will continue to be managed consistent with provisions of the appropriate Acts.

- Scientific research, monitoring, and education: Scientific research, scientific monitoring and educational activities are allowed within the MPA provided the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard (the Minister) approves the Activity Plan.

The Regulations repealed the Endeavour Hydrothermal Vents Marine Protected Area Regulations, as the area formerly protected under those regulations is now subject to the protections afforded under the ThT MPA Regulations. The Endeavor Hydrothermal Vents MPA was Canada’s first Oceans Act MPA, designated in 2003, and covered 97 km2 including the Salty Dawg and the High Rise hydrothermal vents, two relatively pristine hydrothermal vent fields (Figure 2). To help preserve the naturalness of these vent fields for generations to come, the ThT MPA Regulations preclude the approval of an Activity Plan for scientific research or monitoring activity if the activities set out in the plan are likely to adversely affect the ecological integrity of these two vent fields, unless approval of the Activity Plan is necessary to be consistent with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea or customary international law.

It should be noted that the Regulations will be supported by the development of an MPA Management Plan, which DFO and First Nations will develop cooperatively, with stakeholder input. MPA Management Plans are designed to outline objectives for, and management responsibilities associated with, the MPA; describe the implications of MPA designation and plans for ecological monitoring and enforcement; and provide short- and long-term strategies for achieving MPA conservation objectives, as well as compliance and stewardship.

| Activity | General Zone | Union Zone | Dellwood Zone |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pelagic hook and line fishing | Allowed, provided gear does not go below a depth of 500 m from the sea surface | Allowed, provided gear does not go below a depth of 100 m from the sea surface | Allowed, provided gear does not go below a depth of 100 m from the sea surface |

| Midwater trawl | Allowed, provided gear does not go below a depth of 500 m from the sea surface | Prohibited | Prohibited |

| First Nation Food, Social and Ceremonial Fishing table 1 note a | Allowed, provided no bottom contact fishing gear is used | Allowed, provided no bottom contact fishing gear is used | Allowed, provided no bottom contact fishing gear is used |

Table 1 note(s)

|

|||

Compared to the proposed regulations prepublished in the Canada Gazette, Part I, on February 18, 2023, minor clarifications were made to the description of the MPA’s boundaries in the Regulations, in consultation with experts at the Surveyor General Branch of NRCan. The geographic coordinates for points 2 and 4, both on the shared boundary with the Scott Islands Protected Marine Area (PMA), have been adjusted after recalculation by surveyors, and the Regulations specify that point 2 is on the western boundary of the Scott Islands PMA. In addition, the coordinates for points 2, 4, 7, 8, and 9 have been marked as approximate, as indicated by ±, to recognize that the intent is not to formally define coordinates for the seaward limit of the EEZ, the international boundary between Canada and the US, and the western boundary of the Scott Islands PMA through the present statutory instrument.

Regulatory development

Consultation

Consultation occurred over more than a three-year period. From October 2016 until September 2017, engagement activities focused on conveying Canada’s interest in conserving seamounts and hydrothermal vents in the Offshore Pacific Bioregion and gathering local and traditional knowledge via communications with Federal, Provincial and First Nations governments, regional districts, and representatives from marine industries, academia, conservation organizations, and the general public. These engagement activities occurred through letters, emails, phone calls and in-person meetings, as well as through existing industry sector advisory processes.

The Offshore Pacific Advisory Committee (OPAC) was established in September 2017, and served as the primary consultative body for the MPA planning and design process. This multi-interest advisory committee included representation from First Nations, the Province of BC, regional districts and coastal communities, marine industries, including transportation and fishing, non-government organizations with interest in conservation and the environment (the conservation sector) and academia. OPAC met, either in person or by teleconference, eight times between September 2017 and June 2019. It provided advice and feedback on the conservation objective for the area and the rationale for conserving it; the biophysical, socio-economic and resource (e.g. mineral and energy) assessment overview documents; the risks of human activities on the achievement of the conservation objective; and the MPA design and regulatory approach. The OPAC discussions allowed for the consideration and incorporation of stakeholder input throughout the MPA planning and design process. For example, the boundary of the MPA incorporates advice received from OPAC.

Consultation and engagement activities also continued outside of OPAC. DFO met regularly with the Maa-nulth Fisheries Committee (representing the five Maa-nulth Treaty Nations: Toquaht, Uchucklesaht, Ucluelet, Kyuquot/Cheklesaht and Huu-ay-aht First Nations) beginning in 2016. Although all of the Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations (Ditidaht, Huu-ay-aht, Hupacasath, Tse-shaht, Uchucklesaht, Ahousaht, Hesquiaht, Tla-o-qui-aht, Toquaht, Ucluelet, Ehattesaht, Kyuquot/Cheklesaht, Mowachaht/Muchalaht, and Nuchatlaht), the Pacheedaht, Quatsino and Tlatlasikwala First Nations, and the Council of the Haida Nation were invited to participate in OPAC consultations, not all accepted. Thus DFO continued efforts to engage bilaterally with First Nations. Letters were sent to First Nations councils and fisheries managers to try to ensure that information was delivered to all appropriate levels of treaty and non-treaty First Nations governments. DFO followed up regularly via emails, letters and phone calls with information regarding the process, and continued to meet with interested First Nations in their communities to seek their input and ensure an understanding of the Offshore Pacific area and DFO’s interests in its protection. In May 2018, DFO and the technical staff of the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council Nations (NTC) cohosted a West Coast Vancouver Island First Nations Information Forum to share technical information, seek feedback and identify opportunities for interested First Nations to collaborate in this process. Representatives from nine First Nations (Ahousaht, Ditidaht, Tseshaht, Ehattesaht, Hesquiaht, Hupacasath, Tla-o-qui-aht, Pacheedaht and Quatsino) and NTC staff attended. DFO followed up via phone calls and emails with all 14 First Nations represented by the NTC. In November 2018, representatives from Pacheedaht First Nation, the Council of the Haida Nation (CHN), the leadership of the NTC, and the Maa-nulth Fisheries Committee met with DFO to discuss how DFO and First Nations could move forward to cooperatively manage the future MPA. Bilateral discussions additionally occurred, between 2017 and 2022, with Maa-nulth Treaty Nations, the NTC, the CHN, Pacheedaht First Nation, and Quatsino First Nation.

Bilateral consultations with potentially affected fishing sectors also occurred outside of OPAC via existing departmental fisheries sector consultation processes.

In addition, established interdepartmental committees were used as a means of engaging other federal departments, such as Transport Canada, Natural Resources Canada and Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, as well as several different ministries of the BC provincial government. This included the Pacific Interdepartmental Oceans Committee Working Group, the Pacific Region Committee on Ocean Management (RCOM), and the Oceans Coordinating Committee (OCC).

As a result of this multi-year consultation process, concerns of participants were addressed by revising the conservation objective, modifying the approach to assessing the risks posed by human activities, adjusting the boundaries of the MPA, altering the zoning approach, and modifying some of the language within the regulatory intent statement, among other changes.

All those who provided feedback supported allowing pelagic hook and line fishing (i.e. tuna fishing) in the MPA. However, the conservation sector and the CHN expressed a preference that pelagic hook and line fishing not occur over shallow seamounts. In contemplation of input received and the respective conservation objectives, the Regulations allow for fishing with pelagic hook and line gear, as long as the gear does not go below a depth of 100 m from the sea surface in the Union and Dellwood Zones, or a depth of 500 m from the sea surface in the General Zone. The Union seamount is the shallowest area within the MPA, at a depth of approximately 285 m from the sea surface.

There was general support for allowing midwater trawl fishing in the MPA except over the shallow Union and Dellwood seamounts, where many suggested it be prohibited under the MPA’s regulations, as the conservation of the benthic ecosystem was determined to be at risk by this human activity. Consistent with this, the Regulations allow for midwater trawl fishing in the General Zone, provided the gear does not go below a depth of 500 m from the sea surface, but the Regulations do not allow for midwater trawl fishing in the Dellwood or Union Zones.

Mixed recommendations were received regarding allowing bottom contact fishing; a few participants supported small areas being left open, while the majority supported a total prohibition through the MPA’s regulations. Fishing industry representatives expressed dissatisfaction with restricting groundfish fishing on the shallow seamounts and the prohibition of sablefish fishing on the seamounts. Consistent with DFO’s risk assessment results, the risk assessments completed by First Nations concluded that bottom contact gear is of high risk to the seamounts and vent ecosystems. The NTC generally supported bottom contact gear restrictions but expressed a preference that these restrictions be managed under the Fisheries Act, rather than through a blanket prohibition under the Oceans Act MPA regulations. They believed the Fisheries Act would allow for more flexibility in the management of the fishery, as a variation order under the Fisheries Act can be changed or repealed faster and more easily than a regulatory amendment to the MPA’s regulations. The CHN supported prohibiting bottom contact gear for all fisheries via the MPA’s regulations. Pacheedaht First Nation supported restricting commercial and recreational bottom contact gear in the MPA but did not indicate a preference regarding regulatory tool. DFO’s position is that prohibiting fishing with bottom contact gear through the Oceans Act MPA regulations is the most appropriate approach to respecting the reasons for designation and achieving the stated MPA conservation objective: promoting the area’s long-term protection. It also aligns with Canada’s updated MPA Protection Standard.

Marine transportation industry representatives supported the continued use of the Canada Shipping Act, 2001 and other existing legislation to manage marine transportation. The fishing industry also supported the existing regulatory framework for marine transport. However, the conservation sector suggested imposing restrictions on navigation in the MPA. DFO had consulted on potentially including a restriction against vessel anchoring; however, DFO later concluded that this was not necessary to protect the area and the species found therein. The waters in the MPA are too deep for vessels to anchor with traditional anchors that touch the seafloor (the shallowest area within the MPA, the Union seamount, has a depth of approximately 285 m). Vessels would instead use floating anchors when going in offshore areas like this, which is compatible with the conservation objective of the MPA.

Academia generally supported the Activity Plan application process to regulate scientific activity in the MPA but suggested flexibility to ensure scientific research and exploration be allowed to continue in all zones. The Regulations do not restrict the zones in which an Activity Plan application would be considered. However, the Regulations require that in most instances the Activity Plan not be approved if the activity is likely to adversely affect the ecological integrity of the Salty Dawg or the High Rise Hydrothermal Vents. During the review of Activity Plans, the Minister will apply a higher level of scrutiny and a lower tolerance for impacts affecting these sensitive areas.

Prohibiting energy exploration and development was generally supported by all during consultations. In 2019, the Government of Canada announced a new MPA Protection Standard policy, which was further detailed in 2023 to stipulate that oil and gas exploration, development and production be prohibited in new federal MPAs, consistent with the recommendations from the National Advisory Panel on Marine Protected Area Standards. The Regulations align with this commitment.

In a final OPAC meeting in June 2019, DFO presented a revised regulatory intent statement, which described the anticipated MPA boundaries, zoning scheme, conservation objective, prohibitions and allowable activities, and communicated how and why input was or was not applied. In many cases, stakeholder input that was not accepted was due to the suggested prohibitions being contrary to the provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

In May 2021, DFO convened OPAC to give an update on the regulatory process and advise of a change to the planned zoning scheme for the MPA, which altered the number of named zones within the MPA but not the planned protections. OPAC accepted the new zoning scheme.

Prepublication in the Canada Gazette, Part I

The proposed ThT MPA regulations were prepublished in the Canada Gazette, Part I, on February 18, 2023, for a 30-day public comment period. All comments received through the Online Regulatory Consultation System may be viewed on the Canada Gazette’s website. Comments were received from 103 individuals as well as five organizations, namely the BC Seafood Alliance, Oceana Canada, SeaBlue Canada, the BC Chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS-BC) and West Coast Environmental Law. All five organizations, and all but one of the individual commenters, indicated support for the designation of the MPA. Ninety-two of the submissions from individual commenters were a template email of support.

A recurring theme in the comments (mentioned by five of the individual commenters and two commenting organizations) was the desire for effective monitoring and enforcement to ensure compliance with the Regulations and achievement of the conservation objective. DFO agrees that effective monitoring and enforcement is critical to MPA success.

CPAWS-BC and an individual commenter expressed concern about vertical zoning and a desire to see pelagic hook and line fishing prohibited in the seamount zones, which the conservation sector also advocated for during early consultations. The zones defined within the Regulations pertain to the entire vertical profile (i.e. the water column plus seafloor plus subsoil). Fishing activities could be viewed as being vertically managed as fishing activities that occur near the ocean’s surface are allowed, provided the fishing gear does not go below specified depth restrictions. Risk analyses have concluded these fishing activities are compatible with the conservation objective for the ThT MPA. Somewhat related, another commenter expressed a concern that prohibiting bottom contact fishing but allowing other forms of industrial fishing would lead to “working the edge” of the seafloor without technically coming into contact with it. DFO is of the view that the gear depth restrictions specified in the Regulations create a large safety margin between the maximum permitted depth of the gear and the closest seafloor depth.

The BC Seafood Alliance commented that they were broadly supportive of the MPA and protecting special benthic ecosystems. They reiterated their support for the Regulations allowing continued access to pelagic hook and line and midwater trawl commercial fishing. However, they indicated that they felt the financial numbers for the lost commercial fishing access were an underestimate. In response to the comment, DFO reviewed the estimates and analytical approach associated with the 2017 variation orders and ThT MPA and confirmed the validity of its estimates. While the monetized values presented in this Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement (RIAS) are higher than those in the Canada Gazette, Part I, RIAS, this difference is the result of adjusting the estimates from 2020 dollars to 2023 dollars.

SeaBlue Canada, CPAWS-BC and West Coast Environmental Law submitted comments expressing their desire for the Regulations to specifically prohibit the activities identified in Canada’s MPA Protection Standard, to provide clarity and certainty. This was echoed in the template email received from 92 individuals. An individual commenter also suggested the prohibited activities section of the Regulations specifically reference the MPA Protection Standard. DFO has determined these proposed changes to the regulatory text are unnecessary as the general prohibition effectively prohibits the activities identified under the MPA Protection Standard, because these activities are known to disturb, damage, destroy, or remove from the MPA any living marine organism or any part of its habitat, or to be likely to do so. DFO’s communications on the MPA Protection Standard inform stakeholders of Canada’s intention to prohibit oil and gas exploration, development and production, mineral exploration and exploitation, disposal of waste and other matter, dumping of fill, deposit of deleterious drugs and pesticides, and fishing with a bottom trawl gear. CPAWS-BC additionally reiterated the conservation sector’s desire for a prohibition on cable laying within the MPA; however, DFO maintains the suggested prohibition would be contrary to the provisions of UNCLOS.

One individual commenter, a retired fisherman, who was not supportive of the consultative process for the 2017 groundfish fishery closure was interpreted as being not in support of the MPA, or at least its consultative process.

No changes were made to the proposed regulations as a result of the comments received during Canada Gazette, Part I, prepublication.

Modern treaty obligations and Indigenous engagement and consultation

As per the Cabinet Directive on the Federal Approach to Modern Treaty Implementation, an assessment of modern treaty implications was conducted. The assessment concluded that implementation of this MPA would likely not have an impact on the rights, interests and/or self-government provisions of the Maa-Nulth First Nations Final Agreement. Maa-nulth Treaty Nations were consulted throughout the process and indicated they supported Canada’s planned MPA measures.

The Regulations allow FSC fishing to occur within all zones of the MPA, provided that bottom contact fishing gear is not used. The NTC, CHN, Pacheedaht First Nation and Quatsino First Nation indicated support for the ThT MPA’s protection measures and generally support conservation measures in the Offshore Pacific.

During consultations, the NTC, CHN, Pacheedaht First Nation and Quatsino First Nation expressed an interest to collaboratively manage the ThT MPA with DFO. These First Nations indicate the area has cultural importance, and that their fishers visit and fish the area, and historically fished the area for traditional use and commercial purposes. They have stated that these interests are integral to their claims to title and rights, treaties (where applicable), laws, governance systems, and the wellbeing of their cultures, economies, and communities. These First Nations indicate they have lived for millennia on either Haida Gwaii or the west coast of Vancouver Island, relying on and sustainably managing the resources of the Pacific Ocean. In this regard, the First Nations state that the Pacific Ocean provides food, products for ceremonial purposes, and commerce, and it is viewed as the foundation of their societies, cultures and economies. It also represents a means of access to their communities. The spiritual, cultural and material connections between the First Nations and the Pacific Ocean are understood to be profound.

In the spirit of reconciliation, Canada and the NTC, CHN, Pacheedaht First Nation and Quatsino First Nation have signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) outlining how the parties will work together with respect to the planning, operation, management, and use of the ThT MPA. Among other things, the cooperative management MOU provides for an MPA Management Board with First Nation and DFO representation, which will give advice to the decision-makers of all parties.

In advance of the Canada Gazette, Part I, public comment period, DFO sent an email to treaty and non-treaty First Nations in BC to notify them of the opportunity to comment through the prepublication process. In response to this correspondence, the elected Chief Councillor of the Huu-ay-aht First Nation requested dialogue between DFO and the Huu-ay-aht Ha’wiih (the hereditary chiefs of the Huu-ay-aht, a Maa-nulth treaty nation) regarding the planned MPA. DFO met with the Huu-ay-aht Ha’wiih on March 3, 2023, giving a presentation about the planned MPA, how the MPA’s boundaries were adjusted early on in the process, in consultation with the Maa-nulth Fisheries Committee, to exclude overlap with the Maa-nulth domestic fishing areas, and why designation of the MPA was not expected to increase fishing pressure on the Maa-nulth domestic fishing areas. DFO requested that the Huu-ay-aht Ha’wiih follow up if they wanted more information or additional concerns arose. The Huu-ay-aht Ha’wiih have not reached out to DFO following the meeting and did not submit any comments during the Canada Gazette, Part I, public comment period, which concluded on March 20, 2023.

Following the Canada Gazette, Part I, public comment period, DFO received a letter from the Makah Tribal Council, an Indigenous group located in northwestern Washington State, USA, expressing an interest in knowing more about the proposed MPA and how the conservation initiative could affect them, and requesting consultation. DFO sent a letter in response providing more information and inviting the Makah Tribal Council to reach out should they wish a meeting to further discuss the details of the proposed MPA. No response was received by the requested response date of September 7, 2023, nor in the six months following this date.

Instrument choice

Although certain marine activities are regulated under provisions of the Fisheries Act, the Species at Risk Act, the Canada Shipping Act, 2001, and other federal legislation, these existing regulatory mechanisms were not believed to be sufficient to protect the area and the species found therein from a number of existing threats from human activities, including scientific research (seismic research, species sampling and removal of materials from the seafloor, etc.) and emerging threats from human activities, like deep-sea mining.

Voluntary measures would not be sufficient for the protection of the seamounts and hydrothermal vents. A voluntary approach does not provide a regulatory regime and accompanying management measures, making monitoring and enforcement difficult, if not impossible.

A set of variation orders under the Fisheries Act were put in place in 2017 with similar objectives as the Regulations, to manage bottom contact fisheries and implement agreed upon habitat conservation measures for additional protection of corals and sponges in the area. However, variation orders can be issued and revoked by designated DFO officials and are therefore not considered fitting for the long-term protection of an area. The variation orders also only address fishing-related activities.

New regulations were sought to complement existing federal regulatory mechanisms and provide a unifying authority to conserve and protect the unique seamount and hydrothermal vent ecosystems of the MPA and prohibit certain classes of activities to protect them and the species they support from current and potential future pressures. An MPA designated under the Oceans Act is considered to be the most appropriate tool available to provide the protection required for the seamounts and hydrothermal vents because it prioritizes their protection through the management of multiple human activities over the long-term; the general prohibition against activities that will or are likely to disturb, damage, destroy, or remove any living marine organism or any part of its habitat provides protection from the impacts of most new and emerging human activities.

While the Regulations provide the primary tool for protecting the MPA, they in no way lessen the provisions of other legislation, regulations and policies that otherwise contribute to the protection of these habitats.

Regulatory analysis

The socio-economic impacts related to an MPA designation are framed around the concepts of costs versus benefits, regional economic impacts, and the distribution of economic impacts. This is consistent with the approach followed in other analyses undertaken by DFO and is aligned with Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) requirements for a regulatory impact analysis. Changes in values are estimated by comparing a baseline scenario against a scenario under which the MPA designation occurs (the regulatory scenario). It should be noted that the monetized values have been adjusted for inflation since prepublication in the Canada Gazette, Part I, and are now reported in 2023 dollars (previously 2020 dollars).

Baseline scenario

The baseline scenario includes pre-existing regulatory measures such as the Endeavour Hydrothermal Vents Marine Protected Area Regulations and the 2017 variation orders (FN 1241) that prohibited bottom contact fishing activities in the area. While the costs and benefits of the Endeavour Hydrothermal Vents MPA were published with the regulation in Canada Gazette, Part II (PDF) , the cost implications of the variation orders were not published. An analysis of the impacts of the variation order of fishing in the area conducted at that time determined that the closure of fisheries (including halibut, sablefish, rockfish, lingcod, and dogfish fisheries) associated with bottom contact fishing gear affected around 17% of active groundfish vessels. The landed value for groundfish fisheries across the area is estimated to be $154,000 (2023$) per year, or 0.08% of the coast-wide landed value of those fisheries, based on average landings (2007–2016).footnote 6 A portion of this is from the midwater trawl fishery which has continued under the variation orders. The remainder of landings is displaced, and it was assumed that the quota was likely caught outside of the area. As such, some additional negligible costs associated with the displacement were assumed to be incurred.

To estimate the costs of the variation orders, it was also assumed that the harvest from the sablefish seamount lottery fishery from within the EEZ would be lost. Although quantities and share of catch coming from the area were small, the catch is exclusive to the seamount lottery fishery and cannot be made up in the regular quota fishery. Under the baseline, the discounted net profit loss, due to an assumed loss in catch, would amount to $78,000 (2023$) over ten years. While it is possible that some of the catch could be made up at unprotected seamounts outside of the Canadian EEZ, it is not clear to what degree the case will be, given the increased travel required. There is uncertainty around whether the loss of access to the seamounts in the EEZ would negatively impact fishing activities at seamounts in international waters by making those trips financially riskier.

The benefits associated with the variation orders primarily relate to fishing as it only restricts fishing-related activities. There were no immediate benefits of the variation orders; however the longer-term benefits would have been from potential increase in direct use values from harvest spill overs, which can increase the population abundance for commercially important species in adjacent areas.

Regulatory scenario

As previously mentioned in the “Description” section, the Regulations establish a general prohibition against activities that will or are likely to disturb, damage, destroy, or remove from the MPA any living marine organism or any part of its habitat, subject to exceptions. Among other things, this means that

- Commercial, recreational, and Indigenous FSC fishing activities that utilize bottom contact gear are not allowed in all zones of the MPA;

- Midwater trawl fishing is prohibited in the Union Zone and Dellwood Zone and this activity is restricted to a depth of less than 500 m in the General Zone.

Benefits and costs

The benefits of the Regulations include the long-term conservation and protection of a diverse array of significant areas and species and their associated biodiversity, including globally rare hydrothermal vents and a varied network of seamounts. These habitats are both considered biological hotspots for commercially and culturally significant species as well as rare and unique deep-water species. Given the MPA’s vast size, it contributes to conservation by maintaining and protecting many interdependent ecosystems and complement the protection measures used in coastal areas. Large MPAs have been described as important components of a diversified ecological management portfolio that hedges against the uncertainty of global climate change.footnote 7

Maintaining the pristine nature of the EBSAs supports their direct use value for research activities (where consistent with MPA management). The Regulations also strengthen protections relative to the 2017 variation orders that prohibited bottom contact fishing activities in the area, increasing the likelihood of spillover benefits to commercial fisheries. There is some evidence of movement of rockfish and sablefish (known to inhabit the seamounts) between areas of the Pacific EEZ. The strengthening of protections for the EBSAs within the MPA also results in indirect and non-market benefits (e.g. existence values, bequest values) related to the value individuals place on seamounts and hydrothermal vents and the species and biodiversity they support.

No incremental costs due to displaced fishing activity are anticipated for the commercial groundfish fishery beyond those associated with the 2017 variation orders. The landed value obtained from the midwater trawl catch in the MPA is unlikely to be affected by the closure of midwater trawl fishing in the Dellwood and Union zones. Fishers who choose to undertake midwater trawl fishing within the General Zone of the MPA will incur costs for monitoring and demonstrating compliance with the depth restriction. The actual cost incurred will depend on the vessel’s existing methods to track the depth of their nets and their on-board equipment. The incremental cost of monitoring the depth of their nets is expected to be low since the landed value from the midwater trawl in the MPA represents less than 0.5% of annual average coastwide landed value for midwater trawl or $50,300 in 2023 dollars. Even if fishers chose not to engage in midwater trawl fishing in the MPA, they would be able to replace their catch from other areas with negligible incremental costs.

A change in price of groundfish species for Canadian consumers due to the MPA designation is not anticipated as harvest levels are expected to remain the same, and Canada is a price taker for fish products.

Government costs associated with the management of the MPA over ten years are estimated to be just under $4.0 million (2023$) in present value using a discount rate of 7%. The costs are related to collaboration with First Nations on management activities, research, and enforcement, and will be drawn from existing funding.

Rationale

Based on the cost-benefit analysis, the ThT MPA is anticipated to result in incremental benefits to Canadians because of the potential for important long-term ecological benefits gained through the conservation and protection of unique and productive ecosystems, such as the identified EBSAs. Further, the enactment of the Regulations effectively increases the protection for the Endeavour hydrothermal vents area by providing for the Minister’s refusal of an Activity Plan request, which cannot be achieved through other means (such as a variation order). The designation of the ThT MPA formalizes the management strategy for the Salty Dawg and the High Rise hydrothermal vents currently adopted by researchers, to preserve the integrity of these areas for generations to come.

Small business lens

Commercial fishing vessel owners operating within the MPA are assumed to be small businesses (i.e. no individual vessel has annual revenues that exceed $5 million). Some processing plants may be small businesses; however, the proportion or number is unknown. Costs to small businesses have already been realized under the variation orders as outlined in the baseline scenario. The additional costs anticipated from the Regulations are negligible and associated with compliance with depth restrictions. There are not expected to be any administrative or compliance costs for small businesses associated with this regulatory change. The Regulations are the least burdensome option for small businesses as it allows the opportunity for some fishing, without undermining the conservation objective of the MPA.

One-for-one rule

The one-for-one rule does not apply, as the Regulations do not change administrative costs to business. No commercial enterprises are carrying out the activities subject to the requirement to prepare and submit an Activity Plan for scientific and educational activities in the MPA.

The Regulations repealed an existing regulation, the Endeavour Hydrothermal Vents Marine Protected Area Regulations, and replaced it with a new regulatory title, which results in no net increase or decrease in regulatory titles.

Regulatory cooperation and alignment

The ThT MPA protects 2.3% of Canada’s oceans and contributes to Canada’s national and international marine conservation targets.

Internationally, a target to protect 10% of marine and coastal areas by 2020 was agreed to by Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity as part of the 2020 Aichi Targets in 2010. This 10% target was also integrated into the 2015 UN General Assembly’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (the 2030 Agenda), under Goal 14: conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources. As of August 2019, Canada has surpassed this initial 10% target.

In 2018, the G7 published the Charlevoix Blueprint for Healthy Oceans, Seas and Resilient Coastal Communities. In this, the leaders of the G7, recognizing the need for action in line with previous G7 commitments and the 2030 Agenda, committed to support strategies to effectively protect and manage vulnerable areas of our oceans and resources. As an element of this, the leaders of the G7 committed to “advanc[ing] efforts beyond the current 2020 Aichi Targets, including the establishment of marine protected areas (MPAs) where appropriate and practicable . . . .” In line with this, Canada continues to advance marine conservation and set targets beyond the 2020 Aichi Target. The 2019 speech from the throne announced Canada’s intention to work towards a new goal of conserving 25% of Canada’s oceans by 2025. The 2019 and 2021 mandate letters to the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard and the Minister of Environment and Climate Change echoed this 25% by 2025 target. The 2021 mandate letters also included an additional target of 30% by 2030, which Canada helped champion into an international goal during the December 2022 United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) conference, COP15. At the meeting, Parties to the CBD adopted the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, which includes the target to conserve at least 30% of coastal and marine areas globally by 2030 (Target 3).

Thus, the making of the Regulations aligns with international commitments and initiatives to conserve more of our oceans. Designation of the ThT MPA has added 0.88% to Canada’s total marine conservation coverage. The MPA also replaces a marine refuge established in 2017, the Offshore Pacific Seamounts and Vents Closure marine refuge, which was located within the MPA’s boundaries and contributed 1.44% to Canada’s marine conservation targets upon its establishment. Of note, the MPA enhances the protection of this 1.44% of ocean territory by restricting additional activities that could pose a risk to conservation objectives.

A National Advisory Panel on MPA Protection Standards was established in 2018. The objective of the Panel was to provide recommendations on protection standards in MPAs, using International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) guidance as a baseline. In April 2019, the Government of Canada responded to the recommendations, and in 2023 provided further details on its plan to apply the MPA Protection Standard to new federal MPAs including the prohibition of oil and gas exploration, development and production, mineral exploration and exploitation, disposal at sea of waste and other matter, dumping of fill, deposit of deleterious drugs and pesticides, and fishing with bottom trawl gear. These activities are effectively captured by the general prohibition in the Regulations, which prohibits any activity that disturbs, damages, destroys or removes a living marine organism or any part of its habitat or is likely to do so in the MPA. Thus, the ThT MPA aligns with Canada’s MPA Protection Standard, including the clarifications announced in 2023.

The MPA falls within Canada’s EEZ; therefore, UNCLOS applies. As a result, the Regulations are aligned with the relevant provisions of UNCLOS (i.e. Canada has limited sovereign rights to regulate foreign activities and vessels in its EEZ, as set out in UNCLOS) and therefore although the Regulations apply to international parties there are no broader international regulatory implications.

In addition, the Canada-US Pacific Albacore Tuna Treaty, which allows for the commercial harvest of Pacific Albacore Tuna in the high seas, Canadian waters and USA waters by both Canadian and US licensed vessels, is unaffected by the Regulations. Further, Canada has numerous obligations related to the management of Pacific Albacore Tuna which are a result of Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission and Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission resolutions. These obligations are unaffected by the Regulations.

Strategic environmental assessment

In accordance with the Cabinet Directive on the Environmental Assessment of Policy, Plan and Program Proposals, a strategic environmental assessment was conducted on this regulatory proposal.

Designation of the MPA results in positive environmental effects. The Regulations limit human activities in the MPA and ensure ongoing activities will not negatively impact the area’s sensitive benthic environments, thereby providing long-term, comprehensive protection to the area.

Direct outcomes include the protection of unique, vulnerable, and significant habitats and the associated biodiversity they support; maintaining many interdependent ecosystems allowing for more holistic conservation; and subsequent increased ability for Canada to meet its marine conservation targets. Minimal direct negative outcomes may be experienced by fishers. Prior to 2018, landed value from the integrated groundfish fishery within the MPA’s boundaries represented approximately 0.08% of that fishery’s landed value. In some cases, fishers who fished in the MPA achieved 1% of their yearly income from the area. It is expected that this quota can be harvested elsewhere.

Indirect outcomes include the MPA promoting the replenishment of fish stocks within its boundaries and the potential spillover to surrounding areas, possibly leading to an increase in future harvests in the proximity of the MPA boundaries; and incremental benefits to Canadians because of the potential for important long-term ecological benefits gained through the conservation and protection of unique and productive ecosystems, such as the identified EBSAs.

The establishment of the MPA is consistent with the principles of Canada’s vision for sustainable development and the 2022 to 2026 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy (FSDS). Establishment of the MPA positively impacts Goal 14: Conserve and Protect Canada’s Oceans, which includes the target of conserving 25% of marine and coastal areas by 2025, and 30% by 2030, and identifies implementation strategies of continuing to establish Oceans Act MPAs and use legislation and regulations to protect coasts and oceans.

Gender-based analysis plus

No incremental gender-based analysis plus (GBA+) impacts have been identified for this initiative. During consultations, no concerns were expressed regarding the potential for the MPA to disproportionately impact different groups. As discussed in the baseline scenario, most fishing industry adjustment already occurred in response to a 2017 prohibition on bottom contact commercial and recreational fishing activities in the area, implemented through variation orders under the Fisheries Act. The only harvest impact associated with the variation orders was a small amount of harvest from the sablefish seamount lottery fishery, which is estimated to be $78,000 (2023$) in net profit loss over a ten-year period if it cannot be made up at unprotected seamounts outside of the EEZ. The Regulations may result in negligible incremental costs for vessels choosing to engage in midwater trawl fishing within the MPA to monitor compliance with depth restrictions in the General Zone. No impacts to seafood processors are anticipated.

According to the 2016 Canadian Census, the majority of fishing vessel masters and fish harvesters in British Columbia are male (85%), though 25% of deckhands are female and slightly more than 50% of the seafood processing sector labour force is female. The difference between the above numbers (percentage of total labour force) and those from the percentage of total employed labour force is within 3% for all categories. As a result, female fish harvesters and processors were assumed not to be disproportionately affected by the variation orders.

While negligible incremental impacts are anticipated as a result of these Regulations, data limitations do not allow any detailed analysis of the demographic characteristics of the stakeholders, such as race, family status, cultural background, indigenous identity, income level, or language. Assumptions could be made, though knowledge of fishing practices indicate that this is often misleading.

Implementation, compliance and enforcement, and service standards

Implementation, compliance and enforcement

The Regulations come into force upon registration.