Regulations Amending the Passenger Automobile and Light Truck Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations: SOR/2023-275

Canada Gazette, Part II, Volume 157, Number 26

Registration

SOR/2023-275 December 15, 2023

CANADIAN ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION ACT, 1999

P.C. 2023-1297 December 15, 2023

Whereas, under subsection 332(1)footnote a of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 footnote b, the Minister of the Environment published in the Canada Gazette, Part I, on December 31, 2022, a copy of the proposed Regulations Amending the Passenger Automobile and Light Truck Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations, substantially in the annexed form, and persons were given an opportunity to file comments with respect to the proposed Regulations or to file a notice of objection requesting that a board of review be established and stating the reasons for the objection;

Whereas, under subsection 93(3) of that Act, the National Advisory Committee has been given an opportunity to provide its advice under section 6footnote c of that Act;

And whereas, in the opinion of the Governor in Council, under subsection 93(4) of that Act, the proposed Regulations do not regulate an aspect of a substance that is regulated by or under any other Act of Parliament in a manner that provides, in the opinion of the Governor in Council, sufficient protection to the environment and human health;

Therefore, Her Excellency the Governor General in Council, on the recommendation of the Minister of the Environment and the Minister of Health, makes the annexed Regulations Amending the Passenger Automobile and Light Truck Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations under sections 93footnote d, 160footnote e, 162 and 326footnote f of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 footnote b.

Regulations Amending the Passenger Automobile and Light Truck Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations

Amendments

1 Subsection 1(1) of the Passenger Automobile and Light Truck Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations footnote 1 is amended by adding the following in alphabetical order:

- zero-emission vehicle

- means an automobile that is an electric vehicle, a plug-in hybrid electric vehicle or a fuel cell vehicle. (véhicule zéro émission)

2 Section 2 of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Purpose

2 The purpose of these Regulations is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from passenger automobiles and light trucks by establishing

- (a) emission standards and test procedures that are aligned with the federal requirements of the United States; and

- (b) requirements that, beginning in model year 2026, will incrementally lead to all new passenger automobiles and light trucks being zero-emission vehicles as of model year 2035.

3 Section 3 of the Regulations is amended by striking out “and” at the end of paragraph (c) and by adding the following after paragraph (d):

- (e) requirements respecting the conformity of combined fleets, as defined in subsection 30.1(1), with requirements for zero-emission vehicles; and

- (f) a system of compliance units related to zero-emission vehicles.

4 The heading “Fleet Averaging Requirements” before section 13 of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Fleet Requirements — CO2 Equivalent Emissions

5 Section 15 of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Rounding — general

15 (1) If any of the calculations in these Regulations, except for those in paragraphs 17(4)(b) and (5)(b), subsections 17(6) and (7) and 18.1(1), (5) and (10), sections 18.2 and 18.3 and subsections 18.4(1), 30.13(1), 30.14(3) and 30.21(2) and (3), results in a number that is not a whole number, the number must be rounded to the nearest whole number in accordance with section 6 of the ASTM International method ASTM E29-93a, entitled Standard Practice for Using Significant Digits in Test Data to Determine Conformance with Specifications.

Rounding — nearest tenth of a unit

(2) If any of the calculations in paragraphs 17(4)(b) and (5)(b), subsections 17(6) and (7) and 18.1(1), (5) and (10), sections 18.2 and 18.3 and subsection 18.4(1) results in a number that is not a whole number, the number must be rounded to the nearest tenth of a unit in accordance with section 6 of that method.

Rounding — nearest ten-thousandth of a unit

(3) If any of the calculations in subsections 30.13(1), 30.14(3) and 30.21(2) and (3) results in a number that is not a whole number, the number must be rounded to the nearest ten-thousandth of a unit in accordance with section 6 of that method.

6 Section 17 of the Regulations is amended by adding the following after subsection (7):

CFR version — subsections (6) and (7)

(8) Despite the definition CFR in subsection 1(1), the provisions of the CFR referred to in subsections (6) and (7) are as they read on February 28, 2022.

7 The description of G in section 18 of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

- G

- is the allowance for the use of innovative technologies that result in a measurable CO2 emission reduction, which corresponds to the sum of the allowances calculated in accordance with subsections 18.3(1), (3) or (3.1), and (5); and

8 (1) The portion of subsection 18.1(2) of the Regulations before the formula is replaced by the following:

Fleet average carbon-related exhaust emission value for 2012 model year and subsequent model years

(2) Subject to subsections (8) and (10), a company must calculate the fleet average carbon-related exhaust emission value for each of its fleets of the 2012 model year and subsequent model years using the following formula:

(2) The portion of subsection 18.1(4) of the Regulations before the table is replaced by the following:

Multiplier for certain vehicles

(4) Subject to subsection (5), when calculating the fleet average carbon-related exhaust emission value in accordance with subsection (2) for fleets of the 2017 to 2024 model years, a company may, for the purposes of the descriptions of B and C in subsection (2), elect to multiply the number of advanced technology vehicles, natural gas vehicles or natural gas dual fuel vehicles in its fleet by the number set out in the following table in respect of that type of vehicle for the model year in question, if the company reports that election and indicates the number of credits obtained as a result of that election and the number of vehicles in question in its end of model year report.

(3) Item 9 of the table to subsection 18.1(4) of the Regulations is repealed.

(4) Subsection 18.1(5) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Requirement — plug-in hybrid electric vehicles

(5) A company may make an election under subsection (4) in respect of a plug-in hybrid electric vehicle of the 2017 to 2024 model years only if the vehicle has an all-electric driving range equal to or greater than 16.4 km (10.2 miles) or an equivalent all-electric driving range equal to or greater than 16.4 km (10.2 miles). The all-electric driving range and the equivalent all-electric driving range are determined in accordance with section 1866(b)(2) of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter C, part 86, subpart S, of the CFR.

(5) Subsection 18.1(9) of the Regulations is repealed.

(6) Subsection 18.1(11) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Fuel cell vehicles

(11) For the purposes of subsection (8), a company must count its fuel cell vehicles before counting the other advanced technology vehicles.

9 (1) The portion of subsection 18.3(1) of the Regulations before the formula is replaced by the following:

Allowance for certain innovative technologies

18.3 (1) Subject to subsections (3) and (3.1), a company may elect to calculate an allowance for the use, in its fleet of the 2014 model year and subsequent model years, of innovative technologies that result in a measurable CO2 emission reduction and that are referred to in section 1869(b)(1) of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter C, part 86, subpart S, of the CFR, using the following formula:

(2) The portion of subsection 18.3(3) of the Regulations before the formula is replaced by the following:

Maximum allowance — certain innovative technologies

(3) If, for one of the 2014 to 2022 model years, the 2027 model year or any subsequent model year, the total of the allowances for innovative technologies that a company elects to determine, for a single vehicle, in accordance with the description of A in subsection (1) is greater than 10 grams of CO2 per mile, the company must calculate, using the following formula, the allowance for the use, in its fleet of passenger automobiles or light trucks of that model year, of innovative technologies that result in a measurable CO2 emission reduction and that are referred to in section 1869(b)(1) of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter C, part 86, subpart S, of the CFR:

(3) Section 18.3 of the Regulations is amended by adding the following after subsection (3):

Maximum allowance for 2023 to 2026 model years — certain innovative technologies

(3.1) If, for a model year of the 2023 to 2026 model years, the total of the allowances for innovative technologies that a company elects to determine, for a single vehicle, in accordance with the description of A in subsection (1) is greater than 15 grams of CO2 per mile, the company must calculate, using the formula set out in subsection (3), the allowance for the use, in its fleet of passenger automobiles or light trucks of that model year, of innovative technologies that result in a measurable CO2 emission reduction and that are referred to in section 1869(b)(1) of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter C, part 86, subpart S, of the CFR.

(4) The portion of subsection 18.3(4) of the Regulations before the description of A is replaced by the following:

Adjustment

(4) For the purposes of subsections (3) and (3.1), the company must perform the following calculation and ensure that the result does not exceed 10 or 15 grams of CO2 per mile, respectively:

(Σ (A × Ba) × 195,264) + (Σ (A × Bt) × 225,865)

(Σ Ca × 195,264) + (Σ Ct × 225,865)

where

(5) Subsection 18.3(4) of the Regulations is amended by striking out “and” at the end of the description of Ba and by adding the following after the description of Bt:

- Ca

- is the total number of passenger automobiles in the fleet; and

- Ct

- is the total number of light trucks in the fleet.

10 (1) The portion of subsection 18.4(1) of the Regulations before the formula is replaced by the following:

Allowance for certain full-size pick-up trucks

18.4 (1) Subject to subsections (2) to (4), a company may elect to calculate, using the following formula, a CO2 allowance for the presence, in its fleet, of full-size pick-up trucks equipped with hybrid electric technologies and of full-size pick-up trucks that achieve carbon-related exhaust emission values below the applicable target value:

(2) Subsection 18.4(2) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Allowance limitations — hybrid electric technologies

(2) The allowance for the use of hybrid electric technologies referred to in paragraphs (a) and (b) of the description of AH in subsection (1) may be calculated in respect of full-size pick-up trucks of a model year only if the percentage in the fleet of full-size pick-up trucks of that model year that are equipped with those technologies is equal to or greater than the percentage for that model year set out in section 1870(a)(1) or (2), depending on the technology used, of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter C, part 86, subpart S, of the CFR. The allowance referred to in paragraph (a) of the description of AH may be calculated only for full-size pick-up trucks of the 2017 to 2021, 2023 and 2024 model years.

(3) Subsection 18.4(3) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Allowance limitations — carbon-related exhaust emissions performance

(3) The allowance for full-size pick-up trucks that achieve a carbon-related exhaust emission value referred to in paragraphs (a) and (b) of the description of AR in subsection (1) may be calculated in respect of full-size pick-up trucks of a model year only if the percentage in the fleet of full-size pick-up trucks of that model year that achieve such a value is equal to or greater than the percentage for that model year set out in section 1870(b)(1) or (2), depending on the emission performance achieved, of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter C, part 86, subpart S, of the CFR. The allowance referred to in paragraph (a) of the description of AR may be calculated only for full-size pick-up trucks of the 2017 to 2021, 2023 and 2024 model years.

11 (1) The portion of subsection 20(3) of the Regulations before the formula is replaced by the following:

Calculation

(3) Subject to subsections (3.1) to (3.4), a company must calculate, using the following formula, the credits or deficits for each of its fleets:

(2) The portion of subsection 20(3.1) of the Regulations before the formula is replaced by the following:

Alternative standard — nitrous oxide

(3.1) For each test group in respect of which a company uses, for any given model year, an alternative standard for nitrous oxide (N2O) under subsection 10(1) or 12(1), the company must use the following formula, expressing the result in megagrams of CO2 equivalent, and add the sum of the results for each test group to the number of credits or deficits calculated in accordance with subsection (3) for the fleet to which the test group belongs:

(3) The description of C in subsection 20(3.1) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

- C

- is the alternative exhaust emission standard for nitrous oxide (N2O) under subsection 10(1) or 12(1) to which the company certifies the test group, expressed in grams per mile; and

(4) The portion of subsection 20(3.2) of the Regulations before the formula is replaced by the following:

Alternative standard — methane

(3.2) For each test group in respect of which a company uses, for any given model year, an alternative standard for methane (CH4) under subsection 10(1) or 12(1), the company must use the following formula, expressing the result in megagrams of CO2 equivalent, and add the sum of the results for each test group to the number of credits or deficits calculated in accordance with subsection (3) for the fleet to which the test group belongs:

(5) The description of C in subsection 20(3.2) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

- C

- is the alternative exhaust emission standard for methane (CH4) under subsection 10(1) or 12(1) to which the company certifies the test group, expressed in grams per mile; and

(6) Subsection 20(4) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Calculation and recalculation for the 2017 to 2021 model years

(3.3) A company may elect to calculate or recalculate its credits or deficits for any of its fleets of the 2017 to 2021 model years by making the election referred to in subsection 18.1(4) and by using the equation set out in subsection (3) but replacing the descriptions of A and C with the following:

- A

- is the adjusted fleet average CO2 equivalent emission standard, expressed in grams per mile, calculated in accordance with section 17 but, for the purposes of the descriptions of B and C in subsection 17(3), in the case of advanced technology vehicles, natural gas vehicles or natural gas dual fuel vehicles, the number of vehicles is multiplied by the number set out in the table to subsection 18.1(4) in respect of that type of vehicle for the model year in question;

- C

- is determined by the formula

- Nv + Σ (Ncv × M)

- where

- Nv

- is the number of passenger automobiles or light trucks in the fleet, excluding advanced technology vehicles, natural gas vehicles and natural gas dual fuel vehicles,

- Ncv

- is the number of advanced technology vehicles, natural gas vehicles or natural gas dual fuel vehicles in the fleet, as the case may be, and

- M

- is the multiplier set out in the table to subsection 18.1(4) in respect of the type of vehicle for the model year in question.

2022 to 2024 model years

(3.4) For the 2022 to 2024 model years, if a company makes the election under subsection 18.1(4), the descriptions of A and C in subsection (3) are replaced by the descriptions of A and C in subsection (3.3).

Date of credit or deficit

(4) Subject to subsection (4.1), a company obtains credits or incurs deficits for a specific fleet on the day on which the company submits the end of model year report for the model year in question.

Date of credit or deficit — 2017 to 2021 model years

(4.1) A company obtains credits or reduces its deficits for a specific fleet of the 2017 to 2021 model years if the report includes the following information in respect of that fleet:

- (a) the number of credits or deficits calculated in accordance with subsection (3) and, as applicable, the number of credits or deficits calculated in accordance with subsection (3.3), as well as the difference between the results; and

- (b) a statement that the company has elected to recalculate credits or deficits in accordance with subsection (3.3) and an indication of the number of additional credits, or the reduction in the number of deficits, obtained as a result of that election as well as the number of vehicles in question.

(7) Subsection 20(6) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Time limit — credits for 2017 and 2018 model years

(6) Credits obtained for a fleet of passenger automobiles or light trucks of the 2017 and 2018 model years may be used in respect of any fleet of passenger automobiles or light trucks of a model year that is up to three model years before or up to six model years after the model year in respect of which the credits were obtained, after which the credits are no longer valid.

Time limit — credits for 2019 model year and subsequent model years

(7) Credits obtained for a fleet of passenger automobiles or light trucks of the 2019 model year and a subsequent model year may be used in respect of any fleet of passenger automobiles or light trucks of a model year that is up to three model years before or up to five model years after the model year in respect of which the credits were obtained, after which the credits are no longer valid.

12 Subsection 25(2) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Calculation

(2) The company must calculate the credits or deficits for each of its temporary optional fleets using the formula set out in subsection 20(3).

13 The Regulations are amended by adding the following after section 30:

Combined Fleet Requirements — Zero-emission Vehicles

Interpretation

Definitions

30.1 (1) The following definitions apply in this section, in sections 30.11 to 30.21 and in subsections 33(4.1) to (5).

- combined fleet

- means all automobiles of a specific model year that a company manufactures in Canada or imports into Canada for the purpose of sale of those automobiles to the first retail purchaser. (parc combiné)

- company

- has the same meaning as in section 149 of the Act. (entreprise)

- ZEV requirement

- means the minimum performance required with respect to zero-emission vehicles of a company’s combined fleet for a given model year, as set out in section 30.12. (exigence VZE)

- ZEV value

- means the actual performance with respect to zero-emission vehicles of a company’s combined fleet for a given model year, calculated in accordance with section 30.13(1). (valeur VZE)

Exclusion — emergency vehicles and fire fighting vehicles

(2) Despite the definition combined fleet in subsection (1), a company may, for the purposes of sections 30.11 to 30.21, elect to exclude emergency vehicles and fire fighting vehicles from its combined fleet of any model year, if it reports that election in its end of model year report for that model year.

Exclusion — automobile being exported

(3) The definition combined fleet in subsection (1) does not include any automobile that is being exported and that is accompanied by written evidence establishing that it will not be sold or used in Canada.

General

Requirement respecting ZEV value

30.11 Subject to sections 30.14 to 30.21, a company must ensure that the ZEV value of its combined fleet, calculated in accordance with section 30.13, of the 2026 model year and subsequent model years meets or exceeds the ZEV requirement for the model year in question.

ZEV Requirement for Combined Fleet

ZEV requirement by model year

30.12 The ZEV requirement for a company’s combined fleet for a model year in column 1 of the following table is set out in column 2.

| Item | Column 1 Model year |

Column 2 ZEV requirement |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2026 | 0.20 |

| 2 | 2027 | 0.23 |

| 3 | 2028 | 0.34 |

| 4 | 2029 | 0.43 |

| 5 | 2030 | 0.60 |

| 6 | 2031 | 0.74 |

| 7 | 2032 | 0.83 |

| 8 | 2033 | 0.94 |

| 9 | 2034 | 0.97 |

| 10 | 2035 and subsequent | 1 |

ZEV Value for Combined Fleet

Calculation of ZEV value

30.13 (1) A company must calculate, for the 2026 model year and subsequent model years, the ZEV value of its combined fleet using the following formula:

-

- (A ÷ B) + C

- where

- A

- is the total number of electric vehicles and fuel cell vehicles in the combined fleet;

- B

- is the total number of automobiles in the combined fleet; and

- C

- is, with respect to plug-in hybrid electric vehicles, the lesser of the following results:

- (a) the contribution of these plug-in hybrid electric vehicles to the actual performance of a company’s combined fleet with respect to zero-emission vehicles, calculated using the following formula:

- (0.15 × A + 0.75 × B + C + D + 0.75 × E + F + 0.75 × G + H) ÷ I

- where

- A

- is, for the 2026 model year, the total number of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles in the combined fleet with an all-electric driving range of at least 35 km and not more than 49 km,

- B

- is, for the 2026 model year, the total number of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles in the combined fleet equipped with less than seven seats with an all-electric driving range of at least 50 km and not more than 64 km,

- C

- is, for the 2026 model year, the total number of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles in the combined fleet equipped with seven seats or more with an all-electric driving range of at least 50 km and not more than 64 km,

- D

- is, for the 2026 model year, the total number of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles in the combined fleet with an all-electric driving range of at least 65 km,

- E

- is, for the 2027 model year, the total number of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles in the combined fleet equipped with less than seven seats with an all-electric driving range of at least 50 km and not more than 79 km,

- F

- is, for the 2027 model year, the total number of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles in the combined fleet equipped with seven seats or more with an all-electric driving range of at least 50 km and not more than 79 km,

- G

- is, for the 2028 model year, the total number of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles in the combined fleet with an all-electric driving range of at least 50 km and not more than 79 km,

- H

- is, for the 2027 and subsequent model years, the total number of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles in the combined fleet with an all-electric driving range of at least 80 km, and

- I

- is the total number of automobiles in the combined fleet, and

- (b) the allowable portion of the contribution of these plug-in hybrid electric vehicles to the ZEV requirement for a company’s combined fleet, calculated using the following formula:

- A × B

- where

- A

- is the ZEV requirement for the model year in question, and

- B

- is the allowable portion of that ZEV requirement, set out in column 2 of the following table, for the model year set out in column 1:

Item Column 1

Model year

Column 2

Allowable portion of ZEV requirement

1 2026 0.45 2 2027 0.30 3 2028 and subsequent 0.20

All-electric driving range

(2) For the purposes of subsection (1), the all-electric driving range is calculated using the following formula, rounded to the nearest whole number or, if the number is equidistant between two consecutive whole numbers, to the higher number:

- A × 0.7

- where

- A

- is the actual charge-depleting range in kilometres, determined in accordance with section 311(j)(4)(i) of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter Q, part 600, subpart D of the CFR, rounded to the nearest tenth of a unit or, if the number is equidistant between two consecutive tenths of a unit, to the higher tenth.

Compliance Unit or Deficit System

Obtaining units

30.14 (1) As of the 2026 model year, a company obtains compliance units in respect of its combined fleet if its ZEV value is greater than the ZEV requirement for the model year in question and the company reports the compliance units in its end of model year report.

Deficits

(2) As of the 2026 model year, a company incurs a deficit in respect of its combined fleet if its ZEV value is less than the ZEV requirement for the model year in question.

Calculation

(3) A company must calculate the compliance units or deficit for its combined fleet of a given model year using the following formula:

- (A − B) × C

- where

- A

- is the ZEV value of its combined fleet of the model year;

- B

- is the ZEV requirement for the model year; and

- C

- is the total number of automobiles in the combined fleet.

Date of units or deficit

(4) A company obtains compliance units or incurs a deficit in respect of its combined fleet on the day on which the end of model year report for the model year in question is submitted.

Use of units — time limit

(5) Compliance units obtained for a combined fleet of any of the 2026 to 2034 model years may be used to offset a deficit incurred in respect of any combined fleet of up to three model years before the model year for which those units were obtained and, at the latest, of the earlier of

- (a) the fifth model year after the model year for which the units were obtained; and

- (b) the 2034 model year.

End of validity

(6) Compliance units are no longer valid after the day on which the company submits its end of model year report for the 2035 model year.

Offsetting Deficits and Use of Units

Deficits

30.15 (1) Subject to subsection (4), a company must use compliance units obtained in respect of its combined fleet of a given model year to offset a deficit incurred in respect of its combined fleet.

Remaining compliance units

(2) A company may bank all or some of any remaining compliance units to offset a future deficit or transfer all or some of them to another company.

Offset

(3) A company may offset a deficit with,

- (a) in the case of a deficit incurred in respect of the 2026 and 2027 model years, a number of units equal to the deficit, consisting of

- (i) compliance units obtained in accordance with section 30.14, early compliance units obtained in accordance with section 30.16 or charging station units created in accordance with section 30.21,

- (ii) compliance units or charging station units that were transferred to it by another company, or

- (iii) a combination of any of these units;

- (b) in the case of a deficit incurred in respect of the 2028 to 2030 model years, a number of units equal to the deficit, consisting of

- (i) compliance units obtained in accordance with section 30.14 or charging station units created in accordance with section 30.21,

- (ii) compliance units or charging station units that were transferred to it by another company, or

- (iii) a combination of any of these units;

- (c) in the case of a deficit incurred in respect of the 2031 to 2034 model years, a number of compliance units equal to the deficit, consisting of compliance units obtained in accordance with section 30.14 or that were transferred to it by another company, or a combination of any of these units.

Offsetting deficits — sum of early compliance units and charging station units

(4) The sum of early compliance units and charging station units, including those charging station units that were transferred to it by another company, that a company uses to offset a deficit incurred in respect of the combined fleet of any of the 2026 to 2030 model years may not exceed, for the model year in question, the amount calculated using the following formula:

- 0.1 × A × B

- where

- A

- is the ZEV requirement for the model year in question; and

- B

- is the total number of automobiles in the combined fleet.

Offsetting deficits 2026 to 2034 model years — time limit

(5) Any deficit incurred in respect of a combined fleet for a given model year must be offset no later than

- (a) in the case of a deficit in respect of the 2026 to 2031 model years, the day on which the company submits the end of model year report of the third model year after the model year for which the company incurred the deficit; or

- (b) in the case of a deficit in respect of the 2032 to 2034 model years, the day on which the company submits the end of model year report for the 2035 model year.

No offset — 2035 model years and subsequent model years

(6) No deficits incurred in respect of a combined fleet for the 2035 model year and subsequent model years can be offset.

Early Compliance Units — Zero-emission Vehicles of the 2024 and 2025 model years

Obtaining units

30.16 (1) A company may obtain early compliance units in respect of its combined fleet of the 2024 and 2025 model year, if there are zero-emission vehicles in its combined fleet, the amount calculated in accordance with subsections (2) and (3) is positive and the company reports those units in the end of model year report for the model year in question.

Calculation — 2024 model year

(2) The number of early compliance units that a company may obtain for its combined fleet of the 2024 model year is equal to the lesser of

- (a) the number of units calculated using the following formula:

- 0.12 × A

- where

- A

- is the total number of automobiles in the combined fleet; and

- (b) the number calculated using the following formula:

- (0.15 × A + 0.75 × B + C + D) − (0.08 × E)

- where

- A

- is the total number of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles in the combined fleet with an all-electric driving range of at least 35 km and not more than 49 km,

- B

- is the total number of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles in the combined fleet equipped with less than seven seats with an all-electric driving range of at least 50 km and not more than 64 km,

- C

- is the total number of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles in the combined fleet equipped with seven seats or more with an all-electric driving range of at least 50 km and not more than 64 km,

- D

- is the total number of electric vehicles and fuel cell vehicles, and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles with an all-electric driving range of at least 65 km, in the combined fleet, and

- E

- is the total number of automobiles in the combined fleet.

Calculation — model year 2025

(3) The number of early compliance units that a company may obtain for its combined fleet of the 2025 model year is the lesser of

- (a) the number of units calculated using the following formula:

- 0.07 × A

- where

- A

- is the total number of automobiles in the combined fleet; and

- (b) the number calculated using the following formula:

- (0.15 × A + 0.75 × B + C + D) − (0.13 × E)

- where

- A

- is the total number of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles in the combined fleet with an all-electric driving range of at least 35 km and not more than 49 km,

- B

- is the total number of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles in the combined fleet equipped with less than seven seats with an all-electric driving range of at least 50 km and not more than 64 km,

- C

- is the total number of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles in the combined fleet equipped with seven seats or more with an all-electric driving range of at least 50 km and not more than 64 km,

- D

- is the total number of electric vehicles and fuel cell vehicles, and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles with an all-electric driving range of at least 65 km, in the combined fleet, and

- E

- is the total number of automobiles in the combined fleet.

Date of units

(4) A company obtains early compliance units with respect to its combined fleet on the day on which the end of model year report for the model year in question is submitted.

Banking

(5) A company may bank but cannot transfer its early compliance units.

End of validity

(6) Early compliance units are no longer valid after the day on which the company submits its end of model year report for the 2027 model year.

Registered Charging Station Installation Project — Charging Station Units

Registration

30.17 Subject to section 30.19, the Minister may, on the application of one company, register a charging station installation project so that charging station units are created if the application contains the information that is required by section 30.18. The Minister will complete registration by no later than December 31, 2027.

Registration application content

30.18 The application for registration of the project must contain

- (a) the name, street and mailing addresses, telephone number and, if any, email address of the company;

- (b) the name, title, street and mailing addresses, telephone number and, if any, email address of the person who is authorized to act on behalf of the company;

- (c) the name, title, street and mailing addresses, telephone number and, if any, email address of its contact person, other than the person referred to in paragraph (b);

- (d) if applicable, the information referred to in paragraphs (a) to (c) with respect to each company and third party that invests in the project;

- (e) the following information with respect to the project:

- (i) the name by which the project is known,

- (ii) the estimated total investment in the project and, if applicable, the amount to be invested by each company and third party and the proportion, expressed as a percentage, of their investment in the total investment in the project,

- (iii) the estimated number of charging stations,

- (iv) the rated power of each station,

- (v) the location of each station, according to the Global Positioning System (GPS), to the fifth decimal place,

- (vi) the anticipated date of commencement of operation of each station, and

- (vii) the estimated number of charging station units to be created; and

- (f) a statement affirming that

- (i) the project targets the installation of charging stations for zero-emission vehicles,

- (ii) the charging stations will be certified for use in Canada and will be installed in a permanent manner in Canada, in locations where there are no charging stations or to increase the number of charging stations already installed at a given location,

- (iii) the charging stations will have a rated power of at least 150 kW,

- (iv) the charging stations can be used, without restricting the power output, at all times and at the same price by all makes and models of zero-emission vehicles that are equipped with a compatible charging port or necessary adaptor to connect to the stations,

- (v) the charging stations will be operational no earlier than on January 1, 2024 and no later than two years after the date of registration of the project, but the date must not be later than December 31, 2027,

- (vi) the charging stations will remain in operation for at least five years,

- (vii) no financial contribution or other benefit will be granted with respect to the project from a government program, and

- (viii) no compliance credits, referred to in sections 102 and 103 of the Clean Fuel Regulations, will be created with respect to the project.

Registration — conditions

30.19 The Minister must not register a charging station installation project under section 30.17 unless the Minister is satisfied that the statement referred to in paragraph 30.18(f) will be complied with.

Cancellation of registration

30.20 The Minister must cancel the registration of any charging station installation project that does not comply with subparagraph 30.18(f)(i), (vii) or (viii).

Creation of charging station units

30.21 (1) A company may create charging station units with respect to any registered charging station project if

- (a) all charging stations became operational no earlier than on January 1, 2024 and no later than two years after the date of registration of the project, but the date must not be later than December 31, 2027; and

- (b) the company reports those units in its end of model year report.

Number of units — one investor

(2) If a company is the only investor in a registered project, the company must calculate the number of charging station units it will create using the following formula:

- A ÷ B

- where

- A

- is the lesser of

- (a) the total amount of the company’s investment; and

- (b) the total of the maximum allowable investment amounts for each charging station, in accordance with the table below; and

Column 1

Rated power of charging stations

Column 2

Maximum investment for each charging station

150 kW to 199 kW $150,000 200 kW and above $200,000

- B

- is $20,000.

Number of units — multiple investors

(3) If a company invests in the registered project with other companies or third parties, that company must calculate the number of charging station units it will create using the following formula:

- (A ÷ B) × C

- where

- A

- is the lesser of

- (a) the total investment amount in the project, and

- (b) the total of the maximum allowable investment amounts for each charging station, in accordance with the table in subsection (2);

- B

- is $20,000; and

- C

- is the proportion of the company’s investment in the project, as compared to the total investment in the project, expressed as a percentage of the total investment.

Date of units

(4) A company creates charging station units with respect to a registered project on the day on which the end of model year report for the model year in question is submitted.

Banking or transfer

(5) A company may bank all or some of the charging station units created with respect to the registered project and transfer all or some of them to another company.

Cancellation of charging station units

(6) The Minister must cancel

- (a) in respect of each charging station of the registered project that does not comply with any of subparagraph 30.18(f)(ii) to (vi), those charging station units created with respect to the station; and

- (b) in respect of the cancellation of the registration of a project under section 30.20, all units created with respect to that project.

End of validity

(7) Charging station units are no longer valid after the day on which the company submits its end of model year report for the 2030 model year.

14 Section 33 of the Regulations is amended by adding the following after subsection (4):

Additional information — early compliance units and charging station units

(4.1) The end of model year report must also contain the following information with respect to the combined fleet of the company:

- (a) as applicable, with respect to any early compliance units obtained,

- (i) the number of units obtained,

- (ii) the total number of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles for which the all-electric driving range is at least 35 km and not more than 49 km,

- (iii) the total number of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles equipped with less than seven seats for which the all-electric driving range is at least 50 km and not more than 64 km,

- (iv) the total number of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles equipped with seven seats or more for which the all-electric driving range is at least 50 km and not more than 64 km,

- (v) the total number of electric vehicles and fuel cell vehicles, and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles with an all-electric driving range of at least 65 km;

- (b) as applicable, with respect to any charging station units created,

- (i) the name and identification number of the charging station installation project for which they were created,

- (ii) if applicable, the information referred to at paragraph 30.18(d) with respect to the project,

- (iii) the total investment in the project and, if applicable, the amount invested by each company and third party and the proportion, expressed as a percentage, of their investment in the total investment in the project,

- (iv) the number of charging stations installed as part of the project and the rated power of each,

- (v) the Global Positioning System (GPS) coordinates to the fifth decimal place and, if any, street address of each charging station,

- (vi) the date on which the charging stations became operational,

- (vii) the number of charging station units that were created with respect to the project, and

- (viii) a statement by each company and third party that invested in the project, indicating the total amount of their investment in the project and, in the case of a company, the number of charging station units they created, if any.

Additional information — charging stations

(4.2) The end of model year reports for the five model years following that in which charging station units are created must also contain the following information:

- (a) the amount of time, in days and hours, during which each charging station is non-operational during the calendar year that corresponds to the year of the end of model year reportand the percentage of that year which that period represented, as well as the reason for any service interruptions; and

- (b) the total number of kWh that the charging stations provided over the course of the calendar year that corresponds to the end of model year report.

Additional information — compliance units and charging station units

(4.3) The end of model year report must also contain the following information with respect to any compliance units and charging station units transferred to or from the company since the submission of the previous end of model year report:

- (a) the name, street address and, if different, the mailing address of the company that transferred the units and the model year in respect of which that company obtained or created those units;

- (b) the name, street address and, if different, the mailing address of the company that received those units and the model year in respect of which that company obtained or created those units; and

- (c) the number of units transferred and the date of the transfer.

Content — zero-emission vehicles

(5) The end of model year report for the model year 2026 and subsequent model years must also contain the following information in respect of the company’s combined fleet:

- (a) if applicable, a statement that the company has elected to exclude emergency vehicles and fire fighting vehicles from its combined fleet;

- (b) the total number of automobiles;

- (c) the total number of electric vehicles and fuel cell vehicles;

- (d) the total number of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles, broken down according to their all-electric driving range, calculated in accordance with subsection 30.13(2), as follows:

- (i) for the 2026 model year,

- (A) those with at least 35 km and not more than 49 km,

- (B) those equipped with less than seven seats and with an all-electric driving range of at least 50 km and not more than 64 km,

- (C) those equipped with seven seats or more and with an all-electric driving range of at least 50 km and not more than 64 km, and

- (D) those with at least 65 km,

- (ii) for the 2027 model year,

- (A) those equipped with less than seven seats and with an all-electric driving range of at least 50 km and not more than 79 km,

- (B) those equipped with seven seats or more and with an all-electric driving range of at least 50 km and not more than 79 km, and

- (C) those with an all-electric driving range of at least 80 km,

- (iii) for the 2028 model year, those with an all- electric driving range of at least 50 km and not more than 79 km, and

- (iv) for the 2028 and subsequent model years, those with an all-electric driving range of at least 80 km;

- (i) for the 2026 model year,

- (e) the ZEV value calculated in accordance with section 30.13 and the actual charge-depleting range, used in the calculation referred to in subsection 30.13(2), for each plug-in hybrid electric vehicle;

- (f) the total number of compliance units or the deficit calculated in accordance with subsection 30.14(3);

- (g) the total number of compliance units used to offset the deficit incurred in respect of the combined fleet for the model year in question or a previous deficit incurred in respect of the combined fleet and, if applicable, the information referred to in subsection (4.3) that applies to those units;

- (h) the number of early compliance units that were used to offset the deficit incurred in respect of the combined fleet for the model year in question or a previous deficit incurred in respect of the combined fleet and the model year with respect to which the units were obtained;

- (i) the number of charging station units that were used to offset the deficit incurred in respect of the combined fleet for the model year in question or a previous deficit incurred in respect of the combined fleet and, if applicable, the information referred to in subsection (4.3) that applies to those units; and

- (j) an accounting, for each model year, of the compliance units, early compliance units, charging station units and deficits.

Coming into Force

15 These Regulations come into force on the day on which they are registered.

REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS STATEMENT

(This statement is not part of the Regulations.)

Executive summary

Issues: As noted in the 2022 Emission Reduction Plan,footnote 2 there is an urgent need to address climate change and move towards a low-carbon economy. Greenhouse gases (GHGs) are primary contributors to climate change and the transportation sector accounts for 28% of domestic greenhouse gas emissions in Canada. Passenger cars and light trucks account for about 40% of the transportation sector’s emissions.footnote 3 Reducing emissions in all sectors, including transportation, is necessary to tackle climate change and reach the Government of Canada’s emission reduction target of 40% to 45% below 2005 levels by 2030 and net zero by 2050.

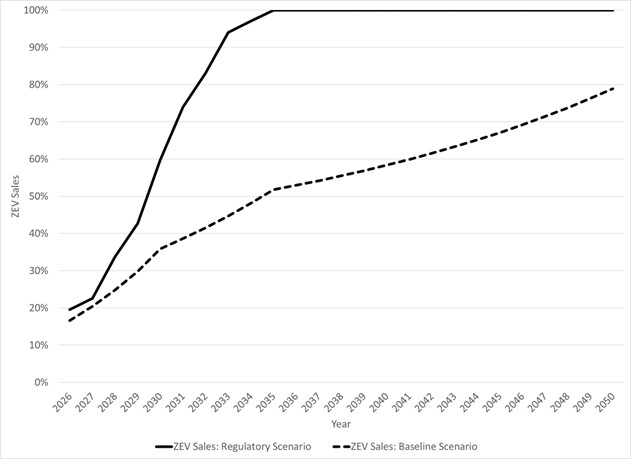

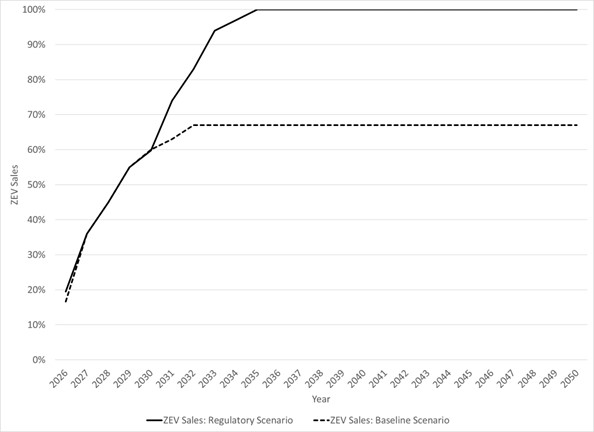

Description: The Regulations Amending the Passenger Automobile and Light Truck Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations (hereinafter referred to as the “Amendments”) will require that a specified percentage of manufacturers’ and importers’ (henceforth referred to as the “regulatees”) fleets of new light-duty vehicles offered for sale in Canada are zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs). These ZEV sales targets will begin with model year 2026 and reach full stringency by model year 2035. In addition, the Amendments will modify flexibilities and fix provisions related to the pre-2026 model year fleet average GHG emission standards.

Rationale: In March 2022, the Government of Canada published its Emissions Reduction Plan (PDF) [ERP], providing a roadmap to reach its climate commitments, such as reducing national GHG emissions by 40% to 45% below 2005 levels by 2030 under the Paris Agreement and achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. To reduce emissions from the transportation sector, the ERP included a plan to introduce a regulated ZEV sales target requiring that 100% of passenger car and light truck sales be zero-emission vehicles by 2035, with interim targets of at least 20% by 2026, and at least 60% by 2030.

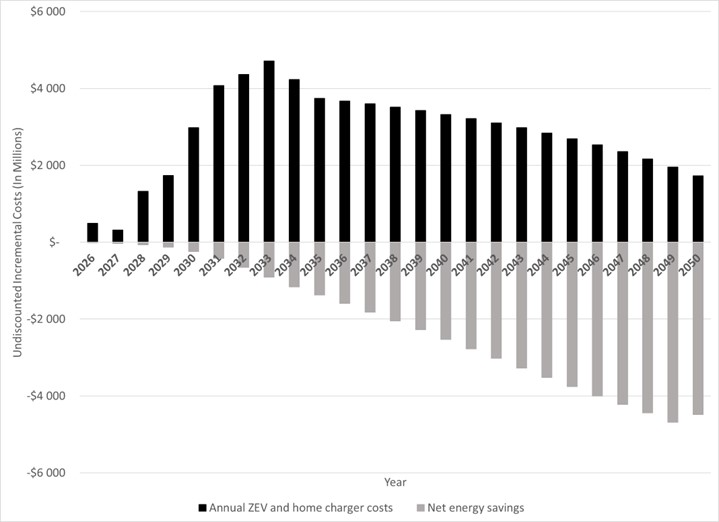

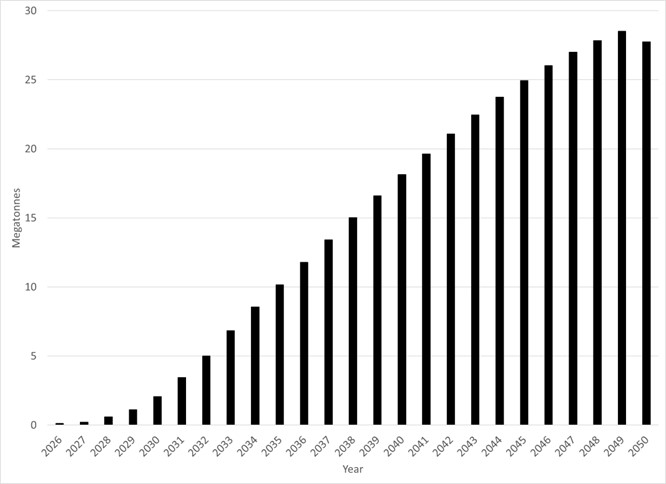

Cost-benefit statement: The Amendments are estimated to have incremental ZEV and home charger costs of $54.1 billion from 2024 to 2050 for consumers who switch to ZEVs in response to the Amendments. These same consumers are expected to realize $36.7 billion in net energy savings over the same time period. The Amendments are also estimated to result in cumulative GHG emission reductions of 362 megatonnes (Mt), valued at $96.1 billion in avoided global damages. These GHG emission reductions will help Canada meet its international GHG emission reduction commitments for 2030 and 2050. The Amendments are thus estimated to have total benefits of $132.8 billion, and net benefits of $78.6 billion.

Issues

As noted in the 2022 Emissions Reduction Plan,footnote 2 there is an urgent need to address climate change and move towards a low-carbon economy. Greenhouse gases (GHGs) are primary contributors to climate change, and the transportation sector accounts for 28% of domestic greenhouse gas emissions in Canada. Passenger cars and light trucks account for about 40% of the transportation sector’s emissions.footnote 4 Decreasing emissions in all sectors, including transportation, is necessary to tackle climate change and reach the Government of Canada’s GHG emissions reduction target of 40% to 45% below 2005 levels by 2030 and net zero by 2050.

Additionally, the Passenger Automobile and Light Truck Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations (PALTGGER or the Regulations) require changes to administrative provisions and compliance flexibilities for pre-2026 model years, based on a 2021 departmental review of the Regulations. The incorporation by reference of the U.S. light-duty vehicle fleet average GHG emission standards also needs to be changed from ambulatory to static in response to the United States Environmental Protection Agency’s (U.S. EPA) proposal to change the numbering of the section of the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) that is referenced in the Passenger Automobile and Light Truck Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations.

Background

The Regulations were published in October 2010 under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA), establishing GHG emission standards for light-duty vehicles (LDVs) of the 2011 to 2016 model years, in alignment with new U.S. EPA standards. These Regulations required importers and manufacturers of new vehicles to meet increasingly stringent fleet average GHG emission standards. In 2014, Canada amended the Regulations to establish GHG emission standards for the 2017 to 2025 model years, in alignment with revised U.S. EPA standards. These Regulations also adopted an incorporation by reference approach to optimize continued alignment with evolving U.S. EPA regulations.

In 2018, the United States completed a mid-term evaluation of its amended regulations, determining that the standards in later years were too stringent and ought to be reduced. In 2020, a U.S. Final Rule was published to reduce the stringency of the fleet average GHG emission standards for model years 2021 through 2026 from approximately 5% per year to approximately 1.5%. Canadian standards consequently became less stringent given the U.S. GHG emission standards were incorporated by reference into the Regulations. In February 2021, Canada completed its own effortsfootnote 5 to assess the impact of the recent U.S. Final Rule and the feasibility of establishing more stringent fleet average GHG emission standards in Canada relative to those in the U.S. Final Rule. However, the U.S. EPA released a new Final Rule later that year, increasing the stringency by about 10% for model years 2023 and 2026 and by at least 5% for model years 2024–2025. Prior to the publication of the EPA Final Rule, Canada announced through the Strengthened Climate Plan that it would work to align the Regulations with the most stringent GHG emission standards in North America post-2025, whether at the United States federal or state level. On May 5, 2023, the U.S. EPA published a Noticed of Proposed Rulemaking for the Multi-Pollutant Emissions Standards for Model Years 2027 and Later Light-Duty and Medium-Duty Vehicles (hereinafter referred to as the NPRM).footnote 6 This proposal would establish additional annually increasing GHG vehicle emission standards of about 13% per year for light-duty vehicles from model years (MYs) 2027 to 2032 in addition to new air pollutant standards. Aligning with these GHG emission standards would require a separate regulatory process, following publication of the U.S. final rulemaking.

In June 2021, the Government of Canada approved a renewed and integrated zero-emission vehicle (ZEV) strategy for LDVs, setting a mandatory target for 100% of new LDV sales to be ZEVs by 2035.footnote 7 In March 2022, the Government of Canada published its 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan (PDF) [ERP], providing a roadmap to reach its climate commitments, such as reducing national GHG emissions by 40%–45% below 2005 levels by 2030 under the Paris Agreement, and achieving net-zero GHG emissions by 2050. The ERP included a plan to introduce regulations requiring that 100% of passenger car and light truck sales be zero-emission vehicles by 2035, with interim targets of 20% by 2026 and 60% by 2030.

Complementary measures led by other federal departments

Throughout the development of amendments to the Regulations (hereinafter referred to as the “Amendments”), there were extensive consultations and coordination with other government departments, and in particular with Transport Canada (TC), Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), and Innovation, Science, and Economic Development Canada (ISED). Each of these departments is responsible for implementing key complementary measures that are helping to support Canada’s transition from GHG emitting vehicles to ZEVs.

ZEV infrastructure

Since 2016, the Government of Canada has made significant investments in ZEV infrastructure, including through NRCan’s Electric Vehicle and Alternative Fuel Infrastructure Deployment Initiative (EVAFIDI) and the Zero Emission Vehicle Infrastructure Programfootnote 8 (ZEVIP). EVAFIDI,footnote 9 which ended on March 31, 2022, supported the deployment of public fast chargers for electric vehicles coast-to-coast along Canada’s highway system, natural gas stations along key freight routes, and hydrogen refuelling in key metropolitan areas. Budget 2019 provided NRCan with $130 million over five years to implement ZEVIP. Furthermore, the 2020 Fall Economic Statement provided an additional $150 million to further expand Canada’s ZEV infrastructure and deploy electric vehicle and hydrogen refuelling stations in communities, including multi-unit residential buildings, workplaces, on-street and public parking spots.

Budget 2022 included an additional $400 million to recapitalize ZEVIP, and $500 million to Canada’s Infrastructure Bank (CIB) to invest in large-scale ZEV charging and refuelling infrastructure that is revenue generating and in the public interest. The Government of Canada is working to deploy 84 500 chargers and 45 hydrogen refuelling stations by 2029. As of September 2023, NRCan’s two programs have selected 43 050 electric vehicle chargers, 36 hydrogen refuelling stations, and 22 natural gas station projects for funding of which 9 623 are already open. As of October 2023, NRCan’s live stations locator data indicates that ZEV drivers in Canada have access to a total of 24 763 charging ports spread across 10 249 charging station locations.footnote 10

ZEV incentives

Since 2019, the Government of Canada has invested over $2 billion to Transport Canada’s Incentives for Zero-Emission Vehicles (iZEV) Program.footnote 11 This Program provides purchase incentives of up to $5,000 for eligible light-duty vehicles until March 31, 2025, subject to funding availability. To date, over 300 000 incentives have been provided to Canadians and Canadian businesses, with over 50 eligible models to choose from. The iZEV Program is complemented by incentive programs offered by several provincial and territorial governments. The combined impact of federal, provincial, and territorial measures have helped to boost new ZEV market share from 3.1% in 2019 to 8.9% in 2022 and roughly 10% for the first half of 2023, according to S&P Global Mobility.footnote 12 Vehicle transaction prices are regularly assessed to ensure that the iZEV Program is being appropriately targeted, and the Government will continue to do so moving forward.

ZEV industrial transition

Via ISED’s Strategic Innovation Fund (SIF),footnote 13 and through strategic contribution agreements, the Government of Canada has supported industry efforts to accelerate the production of low and zero-emission vehicles, as well as to develop Canada’s battery supply chain. Since 2018, automotive and battery manufacturers are set to invest over $26 billion in Canadafootnote 14 to transition to electric vehicle production and establish a battery supply chain, bolstered by more than $3 billion in support from the SIF,footnote 15 and production-based support from the government via special contribution agreements.

Objective

The objectives of the Amendments are to further reduce GHG emissions in the transportation sector, as laid out in the Government of Canada’s commitment in the ERP. In addition, the Amendments aim to reduce the regulatory burden for companies operating in both the Canadian and U.S. markets, by ensuring the administrative requirements for GHG vehicle emission standards up to model year 2026 are aligned between the two jurisdictions.

Description

The Regulationsfootnote 16 were adopted in 2010 for the purpose of reducing greenhouse gas emissions from passenger automobiles and light trucks by establishing fleet average GHG emission standards and test procedures that are aligned with the federal requirements of the United States. The Amendments introduce new ZEV sales targets, beginning with model year 2026, as well as administrative amendments to the current Regulations for vehicles up to MY 2026, beginning with MY 2017. The incorporation by reference of the U.S. light-duty vehicle fleet average GHG emissions standards will also be changed from ambulatory (where the current version of a specified provision is incorporated into Canadian regulations, including any future modifications to that provision) to static (where the version of a specified provision at a fixed point in time is incorporated into Canadian regulations, and would not change if there are future modifications to that provision).

ZEV sales targets

The Amendments are made under CEPA and will establish annual ZEV regulatory targets and a compliance credit system. The Amendments require manufacturers and importers to meet an annual percentage target of new light-duty ZEVs offered for sale in Canada (hereinafter referred to as “ZEV sales targets”). These annual ZEV sales targets are as follows:

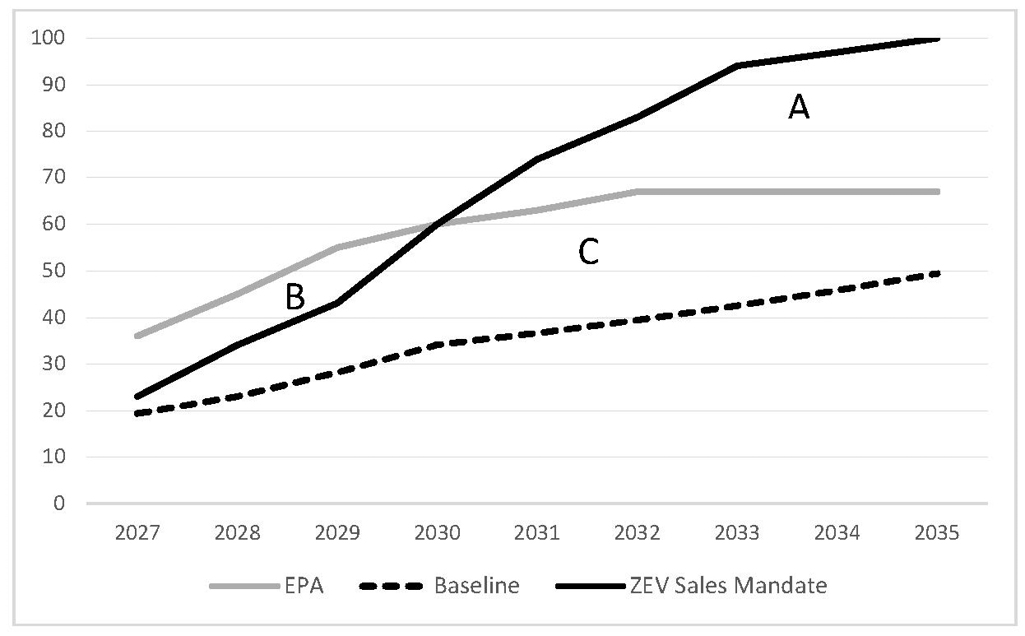

| Model year | ZEV sales targets (%) |

|---|---|

| 2026 | 20 |

| 2027 | 23 |

| 2028 | 34 |

| 2029 | 43 |

| 2030 | 60 |

| 2031 | 74 |

| 2032 | 83 |

| 2033 | 94 |

| 2034 | 97 |

| 2035 and beyond | 100 |

The Amendments will establish a methodology for determining whether the fleet offered for sale in Canada meets the ZEV sales target for a given model year. If a company exceeds its ZEV sales target, it earns compliance units (hereinafter referred to as the “credits”) for excess ZEVs offered for sale. These credits can be used to offset a deficit for a limited number of years in the future. If a company misses its ZEV sales target, it incurs a compliance deficit, which must be satisfied by obtaining credits within a limited time frame. Compliance deficits can be satisfied with banked credits (see below) by purchasing credits from other companies or by creating some credits through financial contribution to charging stations.

The Amendments will allow a company to bank excess credits from exceeding the ZEV sales target in any given model year to use towards compliance for up to five model years after the model year in which the credits were obtained. Companies will not be permitted to use excess credits to meet their sales targets starting in model year 2035 and beyond. In addition, deficits incurred in model years 2026 to 2034 will be required to be offset no later than the third model year after the one in which the company incurred the deficit and no later than model year 2035.

The value of a credit will be based on the type of ZEV and the model year. A battery electric vehicle (BEV), fuel cell vehicle (FCV), or plug-in hybrid electric vehicle (PHEV) with an all-electric range of more than 80 km will receive one credit throughout the entire lifetime of the Regulations. PHEVs with an all-electric range less than 80 km may receive credits for model years 2026 to 2028, as well as early ZEV credits in model years 2024 and 2025 (early ZEV credits are similar to early action credits in other vehicle emission regulations).

Model year 2026: PHEVs with an all-electric range of at least 50 km and with a seating capacity of at least 7, as well as any PHEVs with an all-electric range of at least 65 km, can earn a full credit in model year 2026. PHEVs with an all-electric range of 50 km to 64 km without a seating capacity of at least 7 will receive 0.75 credits and PHEVs with an all-electric range of 35 km to 49 km will receive 0.15 credits during that same time frame.

Model years 2027 and 2028: PHEVs with an all-electric range of 50 km to 79 km and with a seating capacity of at least 7 will receive a full credit in model year 2027 and 0.75 credits in model year 2028. All PHEVs with an all-electric range of at least 80 km will receive a full credit in model years 2027 and 2028. PHEVs with an all-electric range of 50 km to 79 km without a seating capacity of at least 7 will receive 0.75 credits in model years 2027 and 2028.

Model years 2029 and later: PHEVs with an all-electric range of at least 80 km will receive full credit in model years 2029 and beyond. No other PHEVs will receive credits in model year 2029 and subsequent model years.

In addition, the Amendments will limit the contribution of PHEVs towards the ZEV sales target to 45% for model year 2026, 30% for model year 2027 and 20% for model years 2028 and beyond, regardless of the all-electric range of each PHEV.

Finally, the Amendments will also introduce flexibility mechanisms (explained in the next two sections) for companies to earn early ZEV credits in model years 2024 and 2025 and create credits by investing into ZEV charging stations in model years 2024 to 2027.

Early ZEV credits

The Amendments will allow a company to earn early ZEV credits for selling ZEVs in model years 2024 and 2025 within a specific threshold. Companies only earn early ZEV credits for the ZEV portion of their fleet offered for sale that is both below the 2026 target (20%) and above 8% in 2024 and 13% in 2025. The latter percentages were established based on analysis of current ZEV adoption trends in Canada and provincial ZEV regulatory requirements in 2024 and 2025. These credits are earned at the same rate as if they were sold in model year 2026, except there is no limit on the contribution of PHEVs towards the overall early ZEV credit allowance.

In addition, only regulatees in a deficit can use early ZEV credits, and they can only use them to offset their own deficits in model years 2026 and 2027, meaning they cannot be traded to other manufacturers. However, the combined contribution of early ZEV credits and ZEV charging station credits (described below) that can be used to meet a company’s compliance obligation is capped at 10% per model year.

ZEV charging station credits

The Amendments will also allow regulated entities to create credits through contributing to the deployment of charging stations. Regulated entities can submit projects for the development of charging stations to the Minister for approval as soon as the Amendments are published, but no later than December 31, 2027. Projects may involve third parties, but only regulated companies will be authorized to create ZEV charging station credits. To be eligible for charging station credits, the project must involve the installation of charging stations capable of electrical outputs at a rate of at least 150 kW and be located in Canada. The chargers must become operational between January 1, 2024, and December 31, 2027. Additionally, all chargers must be operational within two years of projects receiving approval from the Minister. The chargers must be in a location that is publicly available with equal pricing for all compatible ZEVs (including with adaptors) and be normally available for use 24 hours per day, 7 days per week or, if located on the property of a business, during normal operating hours. The chargers must remain operational for at least the five subsequent years following the start of operation.

Furthermore, the project must not be used to create other compliance credits under another federal regulatory program or will not be funded through any governmental (federal, provincial, or municipal) investment program at any point during its lifetime. Some examples of programs that projects cannot be linked to at the federal/provincial or municipal level include the Clean Fuel Regulations, the ZEVIP, and the Canada Infrastructure Bank.

Once a project has been registered by the Minister following receipt of the application and required affirmation statement, companies can create credits for their investments. Credits will only be authorized to be created for investments up to a maximum amount per project that increases by $150,000 for every charger in the project with a rated power of 150–199 kW and by $200,000 for every charger in the project with a rated power of at least 200 kW. Further details on eligible expenditures will be provided in guidance by the Department and will be in line with Natural Resources Canada’s ZEVIP program.

Regulated companies will earn one charging station credit for each contribution of $20,000. Credits created from charging station deployment may be traded freely and can be used to offset deficits until the end of the 2030 model year. They are limited to satisfying up to 10% of a regulated entity’s compliance obligation in each model year between 2026 and 2030, with the limit in 2026 and 2027 being shared with early ZEV credits used, as described previously.

Should a company fail to comply with its statement to the Minister, the credits for that project will be cancelled.

Administrative amendments to the Regulations

The most significant change to the existing Regulations is a shift to a static incorporation by reference of the GHG standards which are contained in subsections 17(6) and (7) of the Regulations. This is necessary due to revisions proposed by the United States in the recent post-2026 NPRM which would change the section of the CFR in which the U.S. GHG standards are located, and which is currently referenced in Canada’s GHG emission regulations.

Instead of the Canadian regulations referencing the most recent version of the CFR, it will reference a past version of the CFR as it existed on February 28, 2022. This would avoid the need to change all references to the CFR in the current Canadian regulations without affecting the stringency and flexibilities of the various provisions. The pre-2026 GHG standards in the United States took effect on that date and the revisions to the Canadian GHG regulations are based on this version.

Besides this change, the Amendments will make several housekeeping amendments to the pre-2026 model year administrative requirements. These amendments will implement changes identified in Canada’s mid-term evaluation of the Regulations in order to align with some of the changes in the U.S. EPA 2020 and 2021 Final Rules. In addition, the Amendments will make other corrections, clarify provisions and update references in the current version of the Regulations.

Regulatory development

Consultation

Pre-Canada Gazette, Part I, consultations

The Department has consulted with non-governmental organizations (NGOs), industry, academics, other government departments, provincial/territorial/municipal governments, and the public. Starting in August 2020, the Department began to engage the stakeholder community as part of the mid-term review of the PALTGGER. This involved a series of webinars and online consultation sessions in the summer and fall of that year, following the publication of a Final Rule by the U.S. EPA in April 2020. Another webinar session was held in February 2021 following the publication of a revised U.S. final decision document on the mid-term evaluation.

In December 2021, the Department released a discussion paper, which sought input on measures needed to achieve Canada’s 2035 ZEV sales targets for all new LDVs. Stakeholders were invited to provide written feedback until January 21, 2022. In August 2022, a Light-Duty Vehicle Technical Working Group (the “Technical Working Group”) was established to share technical information and views on regulations to reduce GHG emissions from LDVs in Canada and transition towards ZEVs. In addition to these meetings, departmental officials have held over 30 bilateral meetings with stakeholders and partners before the publication of the proposed Amendments.

Comments on proposed Amendments published in the Canada Gazette, Part I

Publication of the proposed Amendments on December 31, 2022, initiated a 75-day comment period during which interested parties were invited to submit their written comments. The Government of Canada’s new online regulatory consultation system was active, and stakeholders were encouraged to submit their comments via that system. The 75-day comment period ended on March 16, 2023. All stakeholder comments that conformed to the terms of use were subsequently posted online.footnote 17

The proposed Amendments were also posted on the Department’s CEPA Environmental Registry Website to make them broadly available to interested parties. The Department informed a broad range of interested parties about the formal consultation process. In early 2023, the Department held group information sessions with representatives of provincial and territorial governments, regulated companies and their representative associations, and environmental NGOs to provide an overview of the proposed Amendments, as well as to answer questions to better inform possible written submissions. The Department also held several meetings with individual regulated manufacturers and importers to better understand their views on the proposed Amendments.

The Department received a total of 215 unique comments from stakeholders regarding the proposed Amendments for pre-2026 GHG emission and ZEV requirements. The summary of comments that follows divides these stakeholders into four distinct categories: industry stakeholders (36); NGOs (20); provincial, territorial and municipal governments and agencies (5); and the public (154). Since the industry stakeholders included a diverse range of organizations, they have been further divided into the following sub-categories: regulated companies (13); associations of regulated companies (2); energy producers and/or suppliers (7); associations of energy producers and/or suppliers (6); an association of heavy-duty vehicle manufacturers (1); and other associations (7).

The Department took these comments into account when developing the final Amendments. The following paragraphs summarize the major issues raised by interested parties on the proposed Amendments and the Department’s analysis leading to the development of the final Amendments. Generally, regulated manufacturers and importers opposed regulated ZEV targets and expressed that Canada would need to put in place stronger supports for the ZEV transition, such as additional charging infrastructure and stronger incentives, and said that without these supports, the Government should adopt less stringent ZEV requirements and increased flexibilities. Regulated companies importing only ZEVs and non-governmental organizations generally advocated for more stringent standards and reduced flexibilities.

Stringency of targets

Some ZEV-only vehicle manufacturers suggested more stringent targets. On the other hand, larger regulated companies with a diversified product line, as well as other associations, suggested less stringent targets, different adoption curves, or only the ERP targets without any interim measures. Other regulated companies requested temporary relief from the targets to give them time to make the necessary investments to develop ZEV products. Similarly, a representative of the automotive supply industry advocated for a more performance-based approach with additional flexibilities particularly for PHEVs. A company whose operations include the production of hydrogen indicated support for the ZEV targets and further stated the importance of regulatory certainty for their business. A regulated company also supported interim targets and alignment with California’s Advanced Clean Car II (ACCII) program.

Many NGOs advocated for more stringent ZEV sales targets, aligned with jurisdictions such as British Columbia, Quebec, and California. They suggested that the proposed targets were too lenient and would be implemented too slowly, thus failing to promote equitable ZEV distribution and rapid GHG emissions reduction. Some NGOs suggested to start mandating ZEV sales targets sooner and remaining open to revisions for upward adjustments. NGOs also argued that more aggressive targets are crucial for meeting Canada’s commitment to reducing GHG emissions.

Response: The Amendments maintain the previously proposed stringency of the targets. These targets will result in a continuous increase in ZEV uptake in line with the commitments made in the ERP.

Making the ZEV targets more stringent in the early years would likely not lead to a meaningful increase in the number of ZEVs sold in Canada, due to the multi-year cycle to design and build new vehicle models. Instead, more stringent targets are likely to result in increased financial flows from traditional automakers to those companies with surplus credits. Financial outflows to these credit-rich companies would reduce the ability of other regulated “traditional automaker” companies to facilitate their own transition to ZEVs and provide consumers with a greater range of ZEV options across all price points.

Using the ERP-defined ZEV targets for only the three model years 2026, 2030 and 2035, without any targets in the intervening years, would reduce the certainty that Canada would continue to make consistent, steady progress towards its ZEV targets. Annual targets also provide more certainty for non-regulated entities supporting the transition, such as the operators of charging stations and the electrical grid. Regulating only 2026, 2030 and 2035 would eliminate the possibility of allowing deficits to be carried forward for up to three years, meaning that the proposed Amendments would likely provide less flexibility. In light of this, the Amendments have maintained the yearly targets for the model years 2026 to 2035 and beyond.

The Amendments incorporate several flexibilities, such as the options to generate early ZEV credits, bank and trade credits, and create credits through contributing to ZEV charging infrastructure. Regulatees may opt to use these flexibilities while they expand their ZEV product portfolio to meet the ZEV sales targets.

The Department has determined that the proposed Amendments struck the appropriate balance of both challenging regulated entities to accelerate the transition to ZEVs in line with Canada’s ERP commitment and ensuring the targets are achievable. Therefore, the Department has not modified the stringency levels of the target values in the Amendments, though it has modified the flexibility provisions in response to comments from stakeholders as detailed further below (see the “Flexibilities” section).

Regional considerations

A wide variety of stakeholders expressed support for regional considerations and requirements. These included several provincial governments and a municipal government agency, several NGOs, some members of the public and a BEV-only regulated company. They stated that the Department should ensure that the proposed Amendments increase ZEV adoption across all parts of the country and advocated for the Department to consider regional requirements. Some stakeholders also expressed concerns about the use of ZEVs in colder northern climates.

Some regulated companies and some associations of regulated companies commented that the proposed Amendments should not include regional requirements. They noted that it is common for dealers to trade vehicles among themselves once they have been supplied by the manufacturer, including across provincial borders. They also noted that different regions of the country are at different levels of ZEV readiness, with some having provincial incentive programs in place, some having substantial charging infrastructure already built, and a consumer base showing strong interest in ZEVs. They felt that regional requirements would be likely to cause shortages of ZEVs in regions with the highest consumer interest and inventories of unsold ZEVs in regions with the lowest consumer interest.

Response: The Department has concluded that ZEV requirements on a national basis remain the most appropriate structure for the Amendments. Departmental analysis indicates that the stringency of the standards is sufficient to drive increased ZEV adoption across all parts of the country even after taking Quebec and British Columbia’s ZEV regulations into consideration.