Corded Window Coverings Regulations: SOR/2019-97

Canada Gazette, Part II, Volume 153, Number 9

Registration

SOR/2019-97 April 15, 2019

CANADA CONSUMER PRODUCT SAFETY ACT

P.C. 2019-322 April 12, 2019

Her Excellency the Governor General in Council, on the recommendation of the Minister of Health, pursuant to section 37 footnote a of the Canada Consumer Product Safety Act footnote b, makes the annexed Corded Window Coverings Regulations.

Corded Window Coverings Regulations

Interpretation

Definitions

1 The following definitions apply in these Regulations.

- cord means any of the following:

- (a) a band, rope, strap, string, chain, wire or any other component that, when any tension is removed, is capable of folding in every direction; or

- (b) any combination of components that are connected end to end that, when any tension is removed, is capable of folding in every direction. (corde)

- corded window covering means an indoor window covering that is equipped with at least one cord. (couvre-fenêtre à cordes)

- loop means a shape, the majority of which is formed by a reachable cord, that creates a completely bounded opening. (boucle)

- reachable with respect to a cord, refers to the part of the cord that any person can touch when the corded window covering has been installed, whether the window covering is fully opened, fully closed or in any position in between. (atteignable)

Specifications

Small parts

2 Every part of a corded window covering that is accessible to a child and is small enough to be totally enclosed in a small parts cylinder as illustrated in Schedule 1 must be affixed to the corded window covering so that the part does not become detached when it is subjected to a force of 90 N applied in any direction.

Lead content

3 Every external component of a corded window covering must not contain more than 90 mg/kg of lead when tested in accordance with the principles set out in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development document entitled OECD Principles of Good Laboratory Practice, Number 1 of the OECD Series on Principles of Good Laboratory Practice and Compliance Monitoring, ENV/MC/CHEM(98)17, the English version of which is dated January 21, 1998 and the French version of which is dated March 6, 1998.

Unreachable cords

4 A cord that is not reachable must remain so, whether the corded window covering is fully opened, fully closed or in any position in between, throughout the useful life of the corded window covering.

Reachable cord with one free end — length

5 A reachable cord with one free end must not exceed 22 cm in length when it is pulled in any direction by the gradual application of force attaining 35 N.

Reachable cord between two consecutive contact points — length

6 A reachable cord with no free end must not exceed 22 cm in length between two consecutive contact points when it is pulled in any direction by the gradual application of force attaining 35 N.

Loop created by a reachable cord — perimeter

7 If a reachable cord is pulled in any direction by the gradual application of force attaining 35 N, the perimeter of any loop, whether it is existing, created or enlarged, must not exceed 44 cm.

Two reachable cords

8 If two reachable cords with one free end each can be connected to one another, end to end, after each has been pulled in any direction by the gradual application of force attaining 35 N, the following criteria must be met:

- (a) the length of the resulting cord must not exceed 22 cm; and

- (b) the perimeter of the loop that is created must not exceed 44 cm.

Information and Advertising

Reference to Canada Consumer Product Safety Act or Regulations

9 Information that appears on a corded window covering, that accompanies one or that is in any advertisement for one must not make any direct or indirect reference to the Canada Consumer Product Safety Act or these Regulations.

Presentation — general

10 The information required by these Regulations must

- (a) appear in both English and French;

- (b) be legible and prominently and clearly displayed and, in particular, the characters must be in a colour that contrasts sharply with the background;

- (c) remain legible and visible throughout the useful life of the corded window covering under normal conditions of transportation, storage, sale and use; and

- (d) in the case of information that is required on the corded window covering, be indelibly printed on the corded window covering itself or on a label that is permanently affixed to it.

11 (1) The required information must be printed in a standard sans-serif type that

- (a) is not compressed, expanded or decorative; and

- (b) has a large x-height relative to the ascender or descender of the type, as illustrated in Schedule 2.

Height of type

(2) The height of the type is determined by measuring an upper case letter or a lower case letter that has an ascender or descender, such as “b” or “p”.

Signal words

12 (1) The signal words “Warning” and “Mise en garde” must be in boldfaced, upper case type not less than 5 mm in height.

Other information — height of type

(2) All other required information must be in type not less than 2.5 mm in height.

Required information — general

13 The following information must appear on every corded window covering, as well as on any packaging in which the corded window covering is displayed to the consumer:

- (a) its model name or model number;

- (b) its date of manufacture, consisting of the year and either the month or week, listed in that order;

- (c) in the case of a corded window covering that is manufactured in Canada, the name and principal place of business of the manufacturer or the person for whom the corded window covering was manufactured; and

- (d) in the case of a corded window covering that is imported for commercial purposes, the name and principal place of business of the manufacturer and the importer.

Instructions — assembly, installation and operation

14 The following instructions must accompany every corded window covering in text, drawings or photographs, or in any combination of them:

- (a) how to assemble the corded window covering and a quantitative list of its parts, if it is sold not fully assembled;

- (b) how to install it; and

- (c) how to operate it.

Warning

15 The following warning or its equivalent must appear on every corded window covering, the packaging of the corded window covering, any accompanying instructions and all of the advertisements for the corded window covering:

WARNING

- STRANGULATION HAZARD — Young children can be strangled by cords. Immediately remove this product if a cord longer than 22 cm or a loop exceeding 44 cm around becomes accessible.

MISE EN GARDE

- RISQUE D’ÉTRANGLEMENT — Les enfants en bas âge peuvent s’étrangler avec des cordes. Enlevez immédiatement ce produit si une corde mesurant plus de 22 cm devient accessible ou si le contour d’une boucle de plus de 44 cm devient accessible.

Repeal

16 The Corded Window Covering Products Regulations footnote 1 are repealed.

Coming into Force

17 These Regulations come into force on the second anniversary of the day on which they are published in the Canada Gazette, Part II.

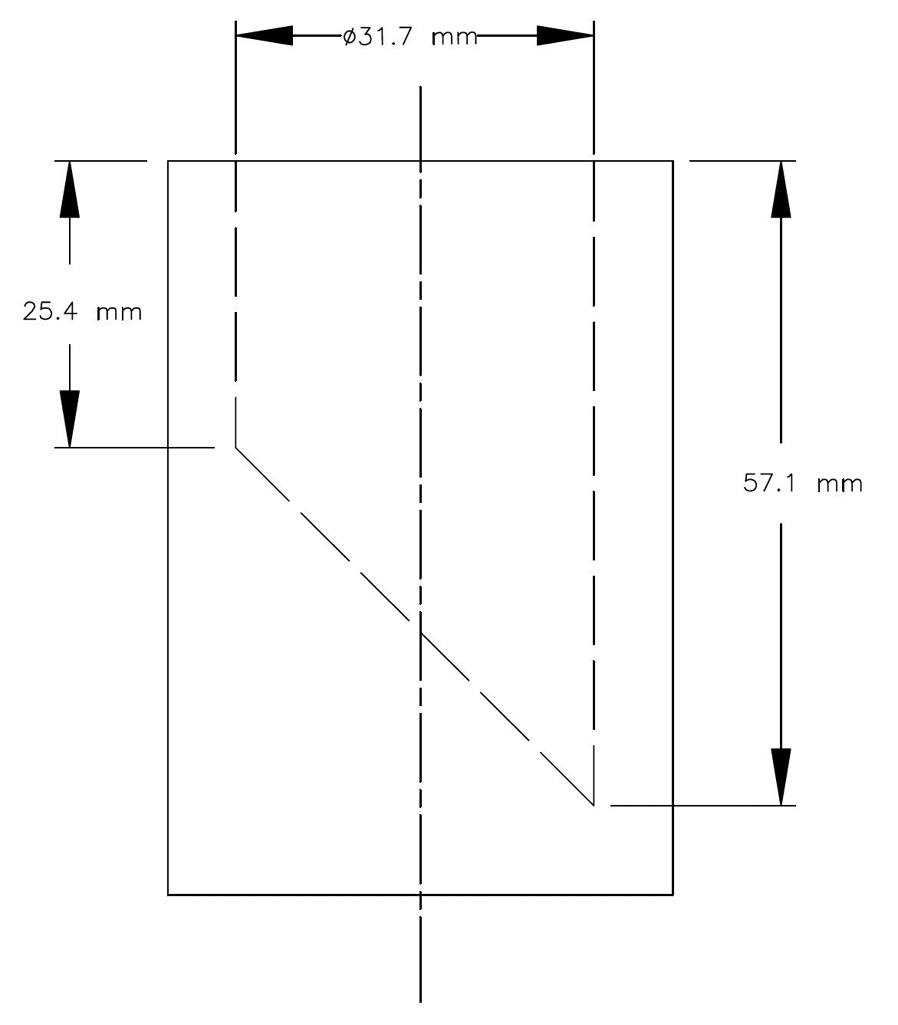

SCHEDULE 1

(Section 2)

Small Parts Cylinder

SCHEDULE 2

(Paragraph 11(1)(b))

Standard Sans-serif Type

REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS STATEMENT

(This statement is not part of the Regulations.)

Executive summary

Issues: Children in Canada continue to be at risk of strangulation from corded window coverings (CWCs). The average fatality rate is slightly more than one child death per year. Since 1991, actions taken to help reduce the risk of strangulation by CWCs, including outreach and education activities, voluntary measures by industry, the development of a Canadian national standard, and the enactment of the Corded Window Covering Products Regulations (CWCPR) in 2009, which incorporate by reference the national standard, have not resulted in a sufficiently reduced fatality rate.

Health Canada is aware of 30 fatalities in Canada involving strangulation from CWCs between 1989 and 2009, before the enactment of the CWCPR, for an average fatality rate of 1.4 child fatalities per year over that period. Over the past nine years, since the CWCPR has been in force, Health Canada is aware of 9 fatalities in Canada for an average fatality rate of 1.0 child fatalities per year.

In 2014, Health Canada completed a risk assessment on CWCs to assess the strangulation hazard, including the effectiveness of the CWCPR to address the hazard. The risk assessment found that CWCs with accessible cords continue to present an unreasonable risk of injury or death to young children, even when they are compliant with the CWCPR.

Updates to the regulatory requirements for these products are necessary to provide stronger protection for children in Canada. Although the voluntary standard for CWCs in the United States was recently updated in 2018, alignment with the requirements of this new standard would allow the risk of strangulation to persist because it allows long accessible cords on many products, it does not sufficiently address the underlying issues leading to fatalities. The existing Canadian market offers many safer, affordable, and easy-to-use alternative operating systems for window coverings. Innovative, safe designs are emerging and can be brought to market in a cost-efficient manner.

Description: The Corded Window Coverings Regulations (“the Regulations”), made under the Canada Consumer Product Safety Act (CCPSA), restrict the length of reachable cords and the size of loops that can be created by a cord in order to help eliminate the risk of strangulation. The Regulations repeal and replace the CWCPR.

Cost-benefit statement: The costs of these Regulations, consisting of incremental costs to components, assembly, research and development, and tooling, will have a present value of $145 million over 20 years (2017 price level, discounted at 7%). The benefits, consisting of reduced mortality rate and savings from reduced testing costs, have a present value of $77 million over 20 years (2017 price level, discounted at 7%). Thus, these Regulations will result in net costs to Canadians of approximately $68 million over 20 years. The net costs have an annualized value of $6.4 million and a cost-benefit ratio of 1.88. This cost is justified by the qualitative benefit of preventing the deaths of young children.

“One-for-One” Rule and small business lens: The “One-for-One” Rule applies, as there will be a decrease in administrative costs of $50,668 annually. These savings are considered an “OUT” under the Rule and are related to the removal of the record-keeping provision that exists in the CWCPR.

The small business lens applies to these Regulations. In order to provide additional flexibility and additional time to determine how best to comply with the new requirements, the Regulations will come into force 24 months following publication in the Canada Gazette, Part II.

International coordination and cooperation: Health Canada and the United States Consumer Product Safety Commission (U.S. CPSC) have collaborated since the 1990s to improve the safety of CWCs, with efforts focused on outreach and education, product recalls, and the development of safety standards. Since 2009, the regulatory approach to CWCs has differed between Canada and the United States, with Canada having mandatory requirements for these products and the United States relying on a voluntary standard.

In 2012, a Pilot Alignment Initiative in which Canada participated with Australia, the United States, and the European Commission (EC) released a consensus statement on CWC safety. This statement indicated that the highest level of protection from the strangulation hazard associated with window coverings was the elimination of accessible cords that could form a hazardous loop under any conditions.

Health Canada supports regulatory cooperation to the extent that it does not compromise the health and safety of people in Canada. The new American voluntary standard does not eliminate the strangulation hazard associated with CWCs. Health Canada will continue to collaborate with the U.S. CPSC to help continue to improve the safety of this product category.

Background

From 1989 to November 2018, Health Canada is aware of 39 strangulation fatalities in Canada related to corded window coverings.

Strangulation incidents related to CWCs have also been reported internationally. From 1996 through 2012, the U.S. CPSC received, on average, 11 reports of strangulation deaths per year. More recent data in the United States suggests no significant change in this fatality rate. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) notes that between one and two children die in Australian homes every year as a result of CWCs. In the United Kingdom, the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents reports that 18 deaths involving looped blind cords occurred between the beginning of 2010 and early 2015. Each of these fatality rates is roughly comparable to Canada when accounting for the population differences among these jurisdictions.

Health Canada has taken various actions to help reduce the risk of strangulation by CWCs. Since 1991, Health Canada has

- requested that industry voluntarily label CWCs in order to warn consumers of the risk of strangulation (1991, 1996);

- implemented consumer education campaigns and various public outreach strategies, including safety messages; letters to daycares, public health units, health care professionals, and realtor associations for distribution to parents and new home owners; media coverage; product safety publications; multiple information bulletins; a window covering safety web page; public consultation about the regulation of CWC products; an “Out Of Reach” public education campaign; a retail poster; a social media, radio, and print public information campaign; frequent social media safety messaging (1992, 1996, 1998, 2005, 2007, 2008, 2013, 2014 to 2017);

- issued 39 product recalls related to strangulation hazards, along with advisories and consumer alerts (1998, 2000, 2002, 2003, 2008 through October 2018);

- collaborated with other regulatory bodies on initiatives such as the development of and amendments to the American voluntary standard prior to the 2018 update; a joint letter with the U.S. CPSC to the window covering industry encouraging the elimination of the strangulation hazard; a joint consensus letter on a pilot alignment statement with the U.S. CPSC, the EC, and the ACCC sent to standards-development organizations [e.g. ANSI/WCMA, ISO, and the Canadian Standards Association (CSA)] recommending the elimination of the strangulation hazard (1996, 2007, 2010, 2012);

- engaged with industry stakeholders by holding face-to-face meetings to encourage the elimination of the CWC strangulation hazard; sending a letter to industry requesting the voluntary retrofit of Roman shades and roll-up blinds (a follow-up market surveillance project found 91% of Roman shades and 100% of roll-up products were non-compliant with this request); making ongoing requests to eliminate the strangulation hazard via participation in standards-development committees (ANSI/WCMA and CSA) alongside industry and consumer stakeholders (1994, 1998, 2010 through 2016);

- participated in the development of standards by funding a CSA committee to write a Canadian national standard on CWCs; proposing the incorporation by reference of the national standard into the CWCPR; participating in the update to the national standard; encouraging the application of the national standard to eliminate the strangulation hazard (1998, 2007, 2008, 2013, 2014); and

- enacted the CWCPR to incorporate by reference the requirements of the national standard, which was equivalent to the American voluntary standard of that time (2009).

Issues

Despite more than 25 years of public education, active industry engagement, concerted attempts to improve the standard, and the introduction of the CWCPR in 2009, fatalities and injuries continue to occur. None of the risk-mitigation measures undertaken by Health Canada or other stakeholders have resulted in a sufficiently reduced fatality rate. The most impactful risk mitigating measure of the past number of years may reasonably be attributed to the emergence of safer technology that does not pose a risk of strangulation, which has grown significantly in market share.

The CWCPR still allow cords that are long enough to form hazardous loops and be wrapped around a child’s neck, and rely upon safety devices that require additional installation and regular active consumer intervention (e.g. cord cleats). Incident narratives of all of the fatalities that have occurred in Canada, including since 2009 when the CWCPR came into force, state that a long cord became entangled around a child’s neck and strangled them to death. Provisions in the new American voluntary standard, published in January 2018, continue to permit long accessible cords. As long as the root cause of strangulation injuries and fatalities is not adequately addressed, incidents will continue to occur.

Updated regulations with stronger safety requirements are needed to better protect children in Canada. The risk of injuries and fatalities posed by corded window coverings is not justified when safe alternatives exist.

Fatalities and injuries

Pathway to injury

Minimal compression of any of the major blood vessels in the neck can lead to unconsciousness within 15 seconds and brain damage begins to occur after about four minutes without oxygen. Death can occur in less than six minutes.

Evidence shows that toddlers and young children have the ability to gain access to window covering cords in ways that are not anticipated by the caregiver. Children may climb or reach to gain access, cribs or other furniture may be placed near CWCs, or parents may simply underestimate the abilities of the child to access these cords. Given that strangulation occurs quickly and silently, incidents may occur even when caregivers are nearby.

Fatal incidents are sometimes incorrectly perceived to be the fault of caregivers. It is unreasonable to expect caregivers to maintain visual contact with a child at all times. Injuries and fatalities have occurred even with a typical level of supervision. Even if actions are taken most of the time to keep cords away from a child, it is reasonably foreseeable that there will be times when safety devices are not used, for instance, when the caregiver’s attention is divided, or the product is used by another person (grandparent, babysitter) who is not aware of the risks and is unfamiliar with the use of a safety device. As per existing requirements, many CWCs already come with safety devices such as cord cleats or tension devices, yet incidents continue to occur.

The following are examples of three Canadian cases for which Health Canada was able to obtain product details, which illustrate that even when a CWC meets the safety requirements of the CWCPR, it can still pose a fatal strangulation hazard.

Strangulation death of a 14-month-old girl

In September 2012, a 14-month-old girl was strangled in the cords of a CWC installed on a window near her crib. The operating cords were tucked into the highest part of the blinds to prevent the daughter from reaching them. Either the cords fell down, or the child managed to climb up to reach them and then became entangled. Individual cords had become knotted together and formed a hazardous loop.

Health Canada subsequently sampled a product of the same design from the importer for testing. The CWC product met the performance criteria of the CWCPR.

Strangulation death of a two-year-old boy

In November 2012, a two-year-old boy was strangled in the cords of a CWC product. The product was horizontal blinds consisting of one headrail and three panels of blinds, each panel having a set of two separate operating cords with toggles on the ends of the cords.

The manufacturer provided a test report showing the product met the performance criteria of the CWCPR.

Strangulation death of a 20-month-old boy

In July 2018, a 20-month-old boy was strangled by the operating cords of a CWC installed on a window near a bed. It was reported that before the child was found, the CWC was in the fully raised position with the operating cords wrapped up high around the top of the blind. The child was later found entangled in the operating cords.

Health Canada was able to determine the product involved in the incident from original purchasing receipts, and followed up with the manufacturer to obtain test reports. The test reports demonstrated that the product met the performance criteria of the CWCPR.

These incidents highlight the fact that requirements that allow long accessible cords, such as those of the CWCPR and also of the new American voluntary standard, allow the strangulation hazard to persist. These requirements do not address the pathway to injury for all products and rely on active consumer intervention to mitigate the risk, which has repeatedly proven to be ineffective in preventing all fatalities.

Statistics and data sources

The number of deaths in Canada attributed to CWCs in any given year varies, and has ranged between 0 and 4 deaths per year since 1989. Prior to the enactment of the CWCPR, from 1989 to 2009, Health Canada is aware of 30 fatalities in Canada involving strangulation from CWCs for an average fatality rate of 1.4 child fatalities per year over that period. Over the past nine years, since the CWCPR has been in force, Health Canada is aware of 9 fatalities in Canada for an average fatality rate of 1.0 child fatalities per year.

In addition to Health Canada’s database of fatalities and injuries, the Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program (CHIRPP) recorded 15 cord-related incidents involving CWCs between 2011 and 2016. Two children were admitted to hospital for further treatment and there was one death. It is unknown how many of these may be duplicates of reports received by Health Canada, and they have therefore not been included in the calculation of average fatality rates.

Health Canada primarily receives reports of fatalities and injuries related to corded window coverings from coroners, media reports, and hospital injury data. For some incidents Health Canada was able to obtain specific product information, and in each case the CWC that killed the child was compliant with the CWCPR. Since 2009, when the CWCPR came into force, four fatalities have been confirmed to involve compliant products. However, in most cases, product details are missing from these reports. As a result, whether the CWC was compliant to the requirements of the CWCPR is often unknown. Given the less stringent pathway to compliance in the CWCPR, wherein any product with two separate cords of any length is compliant, it assumed that any incident involving tangled cords that wrapped around a child’s neck and strangled them would involve a product that meets the requirements of the CWCPR.

Despite the lack of product details for many incidents, every fatality involving a CWC resulted from a long accessible cord that wrapped around a child’s neck and strangled them. The CWCPR and the new American voluntary standard both continue to allow this hazard.

Gaps in the CWCPR

In 2014, Health Canada completed a risk assessment on CWCs to assess the effectiveness of the CWCPR to address the strangulation hazard. The CWCPR incorporate by reference the requirements of the Canadian national standard, the current version of which is equivalent to the 2012 American voluntary standard. The deficiencies identified in the risk assessment were as follows:

- The requirements focus on loops only and do not address the hazard caused by long accessible cords that can become wrapped around a child’s neck, or that can become knotted or tangled, thereby forming a hazardous loop.

- Loops are still allowed when multiple cords are combined in a cord connector.

- Consumer intervention is required to install certain safety devices (e.g. tension devices, cord stops for stock blinds) and incident data show that they are not always properly installed or used by consumers.

Incidents that have occurred with CWCPR-compliant products have drawn attention to these deficiencies. The risk assessment concluded that the risk of dying due to strangulation on window covering cords is high for one-year-old children in Canada who live in a home where CWCs are used.

Both Health Canada’s risk assessment and the U.S. CPSC’s January 2015 advance notice of proposed rulemaking (ANPR) regarding CWCs stated that CWCs that meet the requirements of the CWCPR and the equivalent 2012 version of the American voluntary standard continue to present an unreasonable risk of injury or death to young children.

In addition to Health Canada’s and the U.S. CPSC’s findings, an article published in The Journal of Pediatrics also identified gaps in how CWCs are regulated. In a 2017 epidemiologic study investigating fatal and nonfatal window blind-related injuries among American children younger than six years of age between 1990 and 2015, the authors concluded: “Despite existing voluntary safety standards for window blinds, these products continue to pose an injury risk to young children. Although many of the injuries in this study were nonfatal and resulted in minor injuries, cases involving window blind cord entanglements frequently resulted in hospitalization or death. A mandatory safety standard that eliminates accessible window blind cords should be adopted” (Onders et al. 2018).

Gaps in the new American voluntary standard

Some stakeholders of the window covering industry have urged Health Canada to harmonize with the new American voluntary standard rather than proceed with updating the Regulations. The latest version of the American voluntary standard was published in January 2018. Corrections were published in May 2018, and the standard takes effect in December 2018. The new American voluntary standard continues to allow CWCs to pose an unreasonable risk of strangulation.

- The requirements for cord length for custom products are not adequate to eliminate the risk.

- Although stock products are required to have no operating cords (or only short or inaccessible ones), inner cords of stock are permitted to be long and accessible. Despite a restriction on the size of loops that can be created, inner cords are allowed loops that can easily fit over a child’s head.

- Moreover, the definition of what is stock and what is custom is somewhat subjective, potentially leading to a greater proportion of products being considered custom over the course of time.

The new American voluntary standard does not sufficiently address the underlying issues leading to fatalities. In the absence of further regulatory action and even assuming 100% compliance with the new American voluntary standard for products in Canada, a risk of strangulation will remain in the Canadian market from custom products and the inner cords of stock products, and incidents are likely to continue.

Standards development process — past efforts and current status

Since 1996 Health Canada has participated in the development of safety standards for CWCs, both in Canada and the United States. Health Canada funded a CSA committee to draft the national standard (CAN/CSA Z600 — Safety of corded window covering products, as amended from time to time) that was incorporated by reference into the CWCPR in 2009, with requirements that were essentially harmonized with the American voluntary standard of that time. Amendments to the national standard (and therefore to the CWCPR) have historically reflected amendments made to the American voluntary standard.

Throughout more than a decade of standards-development processes, including amendments and updates to the CWC standards in Canada and the United States, Health Canada has consistently pointed out gaps related to strangulation. Similar comments have been made by the U.S. CPSC and consumer advocates. However, changes have not been made to either the national standard or the equivalent American voluntary standard, including the most recent update to the American voluntary standard in 2018, that would eliminate the risk of strangulation.

The consensus-based process of standards development for CWCs has not yielded a result that provides adequate protection to children. Some industry stakeholders are of the view that long accessible cords must be permitted to provide for consumer choice and unique use situations, despite safer alternatives being available in the market. So long as the root cause of fatalities is not sufficiently addressed, the development of an adequate standard will not be achieved.

In August 2015, Health Canada published a notice to interested parties, which stated that if a more protective standard for preventing strangulations was not forthcoming, Health Canada would consider taking regulatory action to address the risks from blind cords.

In October 2016, citing the lack of progress by industry in instituting a strong, protective standard, the former Minister of Health announced that Health Canada would move forward with amendments to the CWCPR. Health Canada officials advised the Window Covering Manufacturers Association (WCMA), which is the industry association for CWCs, the accredited standards development organization in the United States and a member of the technical committee for the Canadian national standard, that the Department remained interested in participating in the standards development process. However, Health Canada stated that a proposal based on market segmentation along custom versus stock lines would require evidence of a differential risk.

In November 2016, representatives of the WCMA informed Health Canada that the forthcoming edition of the American voluntary standard would be based on market segmentation along stock and custom lines, and did not provide evidence of a differential risk to justify this approach. In December 2016, Health Canada advised the WCMA that the department would no longer continue to participate on the WCMA standard development committee in order to focus on drafting regulations.

Alignment with the new American voluntary standard

Alignment with the new American voluntary standard would require an update to the Canadian national standard, which is referred to in the CWCPR, to align the requirements.

When evaluating alignment with the requirements of the new American voluntary standard, two options may be considered: full alignment, or alignment with only the “stock” product requirements of the new American voluntary standard for all CWCs in Canada. An analysis of each option is discussed below.

Full alignment with the new American voluntary standard

The new American voluntary standard segments the market based solely on whether the product is completely or substantially fabricated in advance of any consumer request. “Stock” window coverings (substantially fabricated prior to purchase) are subject to strong restrictions on the length of operating cords and are subject to a restriction for the size of loops that can be formed by inner cords, while the operating cords of “custom” products (any product that is not “stock”) are permitted to have long accessible cords. Furthermore, the new American voluntary standard continues to allow for a risk of strangulation by imposing no restrictions on the length of inner cords for either stock or custom products.

The definition of “stock” in the new American voluntary standard is subjective, which may lead to industry treating more products as custom versus stock, effectively circumventing the cord restrictions for stock products. What is “stock” under the new American voluntary standard hinges on the definition of “substantially fabricated.” The interpretation of what constitutes “substantially fabricated” is not definitive, and may create uncertainty for stakeholders about whether products comply with the applicable requirements. During the development of the new American voluntary standard, one stakeholder noted “the current proposed definitions will create confusion among manufacturers, distributors, testing labs, retailers, consumers, and government enforcement officials as to the specific products subject to the new proposed safety standard and could lead to inconsistent market offerings and enforcement” (Retail Industry Leaders Association 2016).

Some existing manufacturing processes may also effectively bypass the cord restrictions imposed on stock products due to the definition of “stock” in the new American voluntary standard. Some components of CWCs can be pre-assembled in one location (foreign or otherwise), and then shipped with final assembly of the remaining components occurring later for delivery of a “custom” product. Such products may be considered “custom” since the finished product is not “substantially fabricated” prior to distribution as the definition of stock requires and, therefore, would be permitted to comply only with the less-protective requirements for custom products and have long accessible cords.

The market segmentation approach of the new American voluntary standard, if adopted in Canada, runs the risk of violating Canada’s international trade agreements. Given that most custom products are domestic and most stock products are imported, the Government of Canada would be exposed to the risk that it is imposing a non-tariff trade barrier by applying different requirements to products from different jurisdictions.

Full alignment with the new American voluntary standard is therefore not appropriate in consideration of both health and safety and trade law risks.

Alignment with only the stock product requirements of the new American voluntary standard for all CWCs

A second option is applying the stock product requirements of the new American voluntary standard to all CWCs in Canada. The new American voluntary standard requires operating systems of stock products to be cordless or have short or inaccessible cords. This would eliminate the strangulation risk associated with operating cords. However, this approach is more prescriptive than the Regulations, which are outcome-based and provide the flexibility for industry to develop innovative safe solutions.

While the provisions in the new American voluntary standard relating to operating cords for stock products would likely be effective at eliminating the strangulation hazard, those relating to inner cords of stock products would not. Stock products are still permitted by the standard to have long accessible inner cords that can wrap around a child’s neck. Furthermore, the requirements for loops that may be formed by inner cords allow a circumference of 125 cm when 22 N of force is applied. (A 45 N pull force test for the creation of inner cord loops with a maximum allowable circumference of 30.5 cm, which has been part of the standard since 2002, has been eliminated in the new American voluntary standard.) The test that remains in the new American voluntary standard is insufficient both in terms of the permissible circumference, which can easily pass over the head of a young child, and the pull force, which a young child is easily capable of exerting.

Alignment with only the stock product requirements of the new American voluntary standard for all CWCs in Canada is not an appropriate approach for Canadian regulation. The stock product requirements of the new American voluntary standard unnecessarily limit compliance solutions available to manufacturers for operating systems with only three design options, and do not adequately address the inner cord strangulation hazard.

Alignment at this time with the new American voluntary standard, whether full or partial, means that many compliant products would still pose an unreasonable risk of strangulation, and could run the risk of violating international trade obligations.

Feasibility of a different approach

While technical solutions may not exist today for all current design types of CWCs, many safe and affordable window coverings that are easy to use already exist in the Canadian market and are available for all sizes of windows. For example, a significant percentage of the Canadian market consists of “cordless” products (with no accessible cords) that can be manufactured to the same size as some of the most common widest corded products. CWCs that shield cords or enclose cords in wands, for example, are also safe alternatives that provide easy-to-access operating controls to the user. Existing designs with easily accessible cords that incorporate retraction mechanisms can also be designed with a pull force that meets the requirements of the Regulations if they do not already do so. Innovative solutions are also emerging for the Canadian market. A third-party firm contracted by Health Canada indicated at least 55 devices, methods or innovations exist with working functional products in the market that enable cords to be made inaccessible by various means.

An industry association has stated to Health Canada and other government departments that no company has engineered its window coverings to meet the requirements of the Regulations, specifically with respect to the pull force requirement for inner cords. This claim has formed the basis for this industry association rejecting the Regulations as “not technically feasible,” and supporting alignment with the new American voluntary standard. However, a 45 N pull force requirement for inner cords, which is more stringent than the 35 N pull force requirement set out in the Regulations, has been in place since 2009 in Canada (in section 6.7 of the national standard referenced in the CWCPR), and has also been part of the American voluntary standard since 2002.

Further discussion of the technical feasibility of the Regulations is set out below under the section “Canada Gazette, Part I, consultation and cost-benefit analysis consultation.”

Objective

The objective of the Regulations is to help eliminate the strangulation hazard and to help reduce the rate of fatal strangulations associated with all CWCs by specifying requirements for construction, performance, labelling, and required product information across all market segments, without prohibiting any innovation that achieves this objective. The Regulations are a set of requirements that address the root cause of the pathway to injury or death by strangulation. Eliminating the hazard from new products would also increase awareness of the hazard posed by some existing products in consumers’ homes, and may help motivate consumers to replace the more dangerous, older products sooner than the full lifespan of the product.

Description

The CWCPR will be repealed and replaced with the Regulations, which specify requirements for construction, performance, labelling, and required product information without reference to the national standard.

The Regulations restrict the length of accessible cords and the size of loops that can be created. The Regulations require that any cord that can be reached must be too short to wrap around a one-year-old child’s neck (i.e. not more than 22 cm in length) or form a loop that can be pulled over a one-year-old child’s head (i.e. not more than 44 cm in circumference) when subjected to the gradual application of force attaining 35 N. Cords that cannot be reached must remain unreachable throughout the useful life of the product. Cords that are shielded or made inaccessible are not subject to the length and loop requirements, though they must remain inaccessible. Cords that can be reached cannot exceed 22 cm in length or create a loop greater than 44 cm in circumference when they are at rest, whether the product is fully covering the window, fully open, or at any position in between. Reachable cords may be any length or have loops of any size so long as a pull force of more than 35 N is required to draw them out. When this force is removed, cords that can be reached must retract to less than 22 cm in length or 44 cm in circumference.

Further to the above-mentioned restrictions, the Regulations will require a warning on the product, packaging, instructions, and associated advertisements that speak to the hazards and specifications outlined above, with instructions to immediately remove the product should those hazards become present.

Coming into force

To provide flexibility for small businesses and help address concerns expressed during consultations, the Regulations will come into force 24 months after the day on which they are published in the Canada Gazette, Part II. During the 24-month period, the CWCPR will continue to apply to all CWCs sold, advertised, imported, or manufactured in Canada.

Regulatory and non-regulatory options considered

Status quo

Under the status quo, CWCs in Canada would continue to be subject to the legislative requirements of the CWCPR. Products that are compliant with the CWCPR would continue to pose a risk to children in Canada. In the absence of any other regulatory or voluntary action, it is likely that an average of approximately one death per year would continue. Under the assumption that Canadian manufacturers would voluntarily adhere to the requirements of the new American voluntary standard when it takes effect, incidents are likely to continue to occur in Canada from custom products and the inner cords of stock products. Therefore, the status quo has been rejected, as it does not adequately protect this vulnerable population.

Voluntary measures

From 1991 to 2009, Health Canada was actively engaged in encouraging industry to take voluntary measures to address the strangulation risk posed by CWCs. Despite ongoing education and active industry engagement, changes sufficient to make products adequately protective were not made. In addition, the United States and Australia have undertaken consultations surrounding mandatory requirements for these products or acknowledged deficiencies in existing rules in their respective jurisdictions, suggesting that existing measures have not been effective at mitigating this risk in their jurisdictions. Since 2009, the CWC market has been subject to regulations in Canada that have not produced the expected outcomes. Health Canada is of the view that further voluntary measures, including the new American voluntary standard that permits a risk of strangulation, will not be sufficient to adequately protect Canadian children.

Education and outreach to consumers

Education measures alone cannot eliminate the strangulation hazard associated with long accessible cords on CWCs. Education efforts by Health Canada, industry, and various non-governmental groups to change consumer behaviour with this product category have not significantly helped reduce strangulation injuries and deaths. Continued outreach activities may be considered a complementary instrument for raising awareness and helping to mitigate the risk from products already in people’s homes. Additional education and outreach activities on their own are unlikely to be any more successful in preventing injuries and deaths than the education campaigns to date.

Prohibition

An outright prohibition on CWCs would be more stringent than what is required to eliminate risks from new window coverings, would unduly restrict consumer choice, and would place a greater financial burden on industry.

Updating the Canadian national standard

Updating the Canadian national standard would likely yield the same result of not eliminating the strangulation hazard that the consensus-based process has produced in the past. Some stakeholders are of the view that long accessible cords must be permitted, and that alignment with the new American voluntary standard is the only option for the national standard. This would continue to allow CWCs to pose a risk of strangulation. Therefore, this option was rejected.

Regulatory approach

All prior approaches, including voluntary measures, industry outreach and education, consumer outreach and education, standards development and incorporation of the national standard by reference into regulation have failed to eliminate the strangulation risk posed by CWCs. Furthermore, alignment with the new American voluntary standard that continues to allow long, accessible cords that pose a risk of strangulation, in spite of the existence of safe alternatives, fails to protect children. Therefore, a regulatory approach where performance requirements that address the underlying issues leading to fatalities are specified in the regulation is the preferred option.

Benefits and costs

Introduction

Prior to the enactment of the CWCPR, from 1989 to 2009, Health Canada is aware of 30 fatalities in Canada involving strangulation from CWCs for an average fatality rate of 1.4 child fatalities per year over that period. Over the past nine years, since the CWCPR has been in force, Health Canada is aware of 9 fatalities in Canada for an average fatality rate of 1.0 child fatalities per year.

According to the WCMA, the target lifespan is 10 years for custom CWCs and 3–5 years for stock CWCs (WCMA 2015a and 2015b). Based on the market share of stock and custom products (as discussed in the “Baseline” section), the weighted average useful life of blinds is about 7 years. This aligns with comments received from industry stakeholders during public consultations that suggested the useful life of blinds was approximately 7 years. Therefore, we estimate that the Regulations would reduce risks by about 14% per year, as Canadian households gradually replace existing blinds with new, safer alternatives.

Noting that it has been nine years since the enactment of the CWCPR and that the useful life of blinds is approximately seven years, sufficient time has passed to gauge the impact of the CWCPR.

Assuming broad voluntary compliance with the new American voluntary standard, over the next 20 years, we expect that the Regulations would prevent the death of approximately six Canadian children. In addition to reducing health risks, we expect the Regulations to substantially reduce industry’s cost of testing CWCs. The reduction in testing costs, combined with reduced health risks for children, is estimated to have a present value of $77 million over the next 20 years (2017 price level, discounted at 7%).

As shown in this cost-benefit analysis, industry will assume costs from complying with the Regulations. We estimate the total increase in costs to have a present value of $145 million over the next 20 years (2017 price level, discounted at 7%). We do not know how much of these incremental costs will be borne by manufacturers or passed along to importers, distributors, retailers, and consumers.

Based on this analysis, we estimate the Regulations would have a cost-to-benefit ratio of 1.88, with a net present cost to Canadians of up to $67.7 million. When annualized over the study period, the net present value amounts to a cost of $6.4 million per year.

The analysis is based upon the estimates outlined below. Uncertainties are discussed in the section on sensitivity and uncertainty.

Baseline

This analysis assumes that, without the Regulations, the manufacture, import, and sale of CWCs in Canada would comply with the provisions of the new American voluntary standard beginning in 2019. This analysis also assumes that there will be no material changes to the new American voluntary standard that would affect costs or benefits. Furthermore, this analysis assumes that no other factors will affect benefits or costs in the baseline scenario based on the rationale that there would be no incentive for industry to alter their products to meet requirements beyond those reflected in the new American voluntary standard’s provisions.

Thus, any benefits or costs imposed by the Regulations would be limited to those that are incremental and attributable to moving from the new American voluntary standard to the Regulations.

The new American voluntary standard has different requirements depending on whether the product in question is “stock” or “custom.” Data on the breakdown of stock and custom products in the Canadian market is decidedly limited. In 2015, the WCMA commissioned GLS Research to conduct a web-based survey of a nationally representative sample of 400 Canadian adults. When asked what product they had most recently purchased, 64% said stock, 29% said custom, and 7% were not sure (WCMA 2015a). In addition, recent U.S. data suggests that 80% to 90% of shipments in the analogous American market are stock products (Industrial Economics, Incorporated 2017).

In the absence of additional data, we assume that 75% of the Canadian market consists of stock and 25% custom products. This estimate is, broadly speaking, in line with WCMA’s statement that “stock products account for more than 80% of all window covering products sold in the U.S. and Canada” (WCMA 2018). This analysis assumes the market share of stock and custom products will remain unchanged over the next 20 years.

The new American voluntary standard helps to reduce the risk of strangulation by including restrictions on the length of operating cords of stock products and the size of hazardous loops that can be formed by inner cords on both stock and custom products. However, it continues to allow for a risk of strangulation by imposing no restrictions on the length of inner cords for both stock and custom products, and allows for the formation of loops that can easily pass over a child’s head. Moreover, it provides some exceptions for the provisions relating to the length of operating cords of custom products and the size of loops they can form.

Therefore, the operating cords of custom products and the inner cords of both stock and custom products that comply with the new American voluntary standard may continue to pose a risk of strangulation.

Canadian data on the type of cord involved in CWC strangulations (i.e. operating cords versus inner cords) do not exist. Data from the United States, however, suggest that approximately 80% of strangulations are caused by operating cords and 20% are caused by inner cords (U.S. CPSC 2015). This study considers incidents up to 2012. Accessible inner cords have been subject to hazardous loop testing since the 2002 version of the American voluntary standard, in which free-standing loops were subjected to a 45 N pull force with a maximum allowable loop circumference of 30.5 cm. In 2012, an additional hazardous loop test for inner cords was introduced in the American voluntary standard. This test permits a circumference of 125 cm when subjected to a pull force of 22.2 N. A child is easily capable of exerting this force to create a loop that can easily pass over their head. The new American voluntary standard has dropped the 45 N pull force test, leaving only the 22 N pull force test that allows a loop that can easily fit over a child’s head. The pathway to injury is not eliminated by these requirements.

Based on the foregoing, we have assumed that voluntary compliance with the new American voluntary standard will eliminate the risk of strangulation for operating cords of stock products and have no impact on the risk associated with the operating cords of custom products and the inner cords of both stock and custom products. Based on this assumption and the assumed proportions of stock and custom products (75% and 25%, respectively), the new American voluntary standard will result in an estimated 60% reduction in strangulations (i.e. by adequately addressing stock products [75%] × the risk [80%] presented by operating cords). Conversely, based on this calculation, the new American voluntary standard would not result in any reduction for the remaining approximate 40% of strangulations (i.e. by not adequately addressing stock products [75%] × the remaining risk [20%] of inner cords, plus custom products [25%] × the remaining risk [100%]). About 1.0 child has died per year in Canada since the introduction of the CWCPR. Based on the analysis above, the new American voluntary standard is estimated to reduce the baseline fatality rate to 0.4 child fatalities per year.

In the absence of sufficient data for the Canadian market, data from the United States market is used as the basis for estimating the analogous Canadian market. With respect to the manufacturing location of CWCs, it is estimated that 87% of installed residential CWCs in the United States are produced overseas while 13% are produced domestically (Industrial Economics, Incorporated 2017). With respect to sales, the WCMA estimates that 100 million window-covering units are sold annually in the United States. Applying a prorated adjustment for relative population (10.91%) and household counts (11.39%), the estimate for annual sales of window coverings in Canada is 11 149 143 units. Window coverings that are not affected by the Regulations (cordless, interior shutters, curtains, etc.) are then subtracted from the total, yielding total annual sales in Canada of CWCs with long accessible cords of 9 927 104 units.

Noting that voluntary compliance with the new American voluntary standard will prevent an estimated 60% of strangulation incidents from occurring, the remaining number of units with long accessible cords impacted by the Regulations is estimated to be 3 970 842 annually. The calculations for component and assembly costs are thus derived from this annual number of units that are incrementally impacted by the Regulations.

Benefits

The primary benefit of the Regulations is that children in Canada will no longer be strangled by CWCs. The Regulations will eliminate the remaining 40% of strangulation incidents (that exists in the baseline scenario), thus reducing fatalities to zero. That said, the Regulations will take time to have this effect, as existing non-compliant CWCs are progressively replaced with compliant products.

Assuming an average 7-year life expectancy for all CWCs (75% stock market share × 5 years, plus 25% custom market share × 10 years, rounded up to account for the impacts of price changes on quantities sold), fatalities will decrease by 14% per year following the coming into force of the Regulations. Based on this figure, we estimate that there would still be two deaths over the next 20 years after the coming into force of the Regulations, due to yet-to-be-replaced CWCs. Subtracting these deaths from the total number of expected fatalities over 20 years, the Regulations are estimated to prevent the deaths of six children in Canada over the 20 years after their coming into force.

The reduction in risk faced by families in Canada can be monetized based on the value that people put on risk reduction. In social welfare terms, for an average Canadian, a 1 out of 100 000 reduction in the risk of death is estimated to provide a social benefit valued at $75. To get a total socio-economic benefit across Canadian households, the socio-economic value of this risk reduction is multiplied by the size of the risk reduction generated by the Regulations, and then multiplied by the number of Canadian households with children. Based on this approach, the Regulations will provide a socio-economic benefit valued at approximately $0.4 million per year starting in the first year the Regulations are in effect, increasing to $3.0 million per year once strangulation risks are fully eliminated in the seventh year and beyond. Over the next 20 years, this will provide a social benefit valued at up to $24.2 million (at a 7% discount rate).

The Regulations also substantially reduce testing requirements for the window covering industry in Canada. Under the CWCPR, industry has to perform a wide range of tests to ensure compliance with its requirements and must retain supporting documentation. The types of tests and the costs of these tests vary by product type but are extensive.

By contrast, the Regulations would require significantly fewer tests and omit the most costly tests required by the CWCPR. Based on a weighted average of the testing cost for all products under the CWCPR, costs related to testing would be reduced by approximately 90%, for a saving of approximately $3,100 per product line every time it is tested.

For the purpose of this analysis, it is assumed that approximately 800 CWC businesses with an average of six product lines will test each particular product line once every three years. Averaging out the $3,100 in cost savings over three years results in a saving of $1,025 per product line per year. The Regulations are thus estimated to save industry approximately $4.9 million per year in testing costs. This results in undiscounted cost savings of $89 million over the next 20 years, or $53 million at a 7% discount rate.

Total benefits to Canadians are calculated by adding the benefits associated with reduced mortality risk and the benefit of lower annual product testing costs for industry. Thus, the total benefits are estimated to be $5.4 million in the first year of the Regulations, increasing to $7.9 million by the seventh year and beyond. Cumulative benefits will amount to $134 million over a 20-year period. Discounting future benefits at 7% annually gives a total benefit valued at $77 million over the next 20 years.

Costs

The annual incremental cost imposed by the Regulations is the sum of the yearly costs to make the remaining 3 970 842 otherwise non-compliant units compliant. This includes component, assembly, research and development, and tooling costs. It is important to note that the analysis of costs considers incremental costs (and not the total cost) of all manufacturing activities.

This incremental cost may cause industry to reduce supply, or consumers to reduce demand, thus affecting quantities bought and sold. To the extent that industry assumes cost increases, supply may fall. To the extent that cost increases are passed on to consumers, demand may also fall. Reliable supply and demand curves, which would be necessary to accurately estimate changes in supply and demand, do not exist.

That said, Taylor and Houthakker (2010) estimate that a 1% increase in the price of home goods, which includes CWCs, reduces consumer demand by 0.34%. Panchal (2016) estimates the increased manufacturing cost of safer alternative products for both domestic and overseas production by calculating the increase as a percentage of retail price. The weighted average increase would be approximately 6.1% to the retail cost of window coverings. Assuming that manufacturers do not bear any of the cost increases themselves, thus passing on 100% of the cost increase directly to consumers, demand would fall by about 2.1%.

In the baseline scenario, the number of units with long accessible cords impacted by the Regulations is estimated to be 3 970 842 annually. A 2.1% reduction of that quantity yields 3 887 454 units annually affected by the Regulations. This reduction in annual sales by 83 388 units is estimated to result in annual lost profits valued at $2.66 million.

Components

Safer alternative window coverings already exist in the Canadian market and continue to be developed for all sizes of windows. The component costs associated with some safer alternatives are compared to baseline corded operating systems below.

| Category | Operating System | Component Costs for Operating System table 1 note 1 | Component Costs for Operating System (+20%) table 1 note 2 |

Component Costs for Operating System (+50%) table 1 note 2 |

Incremental Cost vs. Baseline Corded Operating System table 1 note 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline corded operating system | Cord lock (>22 cm cord or >44 cm loop) | $1.14 | $1.37 | $1.71 | |

| Continuous loop (>22 cm cord or >44 cm loop) with tension device | $1.47 | $1.76 | $2.20 | ||

| Safer alternative (no operating cords) | Motorized | $12.08 | $14.49 | $18.12 | $13.29 |

| Cordless (no button) | $2.68 | $3.21 | $4.01 | $1.69 | |

| Cordless (button) | $2.45 | $2.95 | $3.68 | $1.42 | |

| Cordless (with tilt wand) | $3.04 | $3.65 | $4.56 | $2.14 | |

| Wand/slider | $2.62 | $3.15 | $3.93 | $1.63 | |

| Pulley activated cordless | $1.48 | $1.78 | $2.22 | $0.22 | |

| Tethered loop cord | $4.99 | $5.98 | $7.48 | $4.54 | |

| Roller shades (spring assist) | $2.68 | $3.21 | $4.01 | $1.69 | |

| Safer alternative (with operating cords) table 1 note 4 | Cord shroud (fabric) | $0.35 | $0.42 | $0.53 | $0.43 |

| Cord shroud (plastic) | $3.52 | $4.22 | $5.28 | $4.34 | |

| Cord winder retrofit device | $0.60 | $0.72 | $0.90 | $0.74 | |

| Retractable | $1.29 | $1.54 | $1.93 | $1.59 | |

|

Average incremental component cost:

|

$2.81 | ||||

Table 1 note(s)

|

|||||

Based on this analysis, the average incremental component cost of safer alternatives is estimated to be $2.81 per unit.

While a calculation based upon the market share of each type of operating system would be more precise than simply averaging all operating systems together, the future market share of each operating system remains uncertain. In the above calculation, by assigning equal weight to expensive motorized systems that are likely to account for a very small fraction of the market, the calculated average incremental component cost is increased disproportionately. Furthermore, averaging the three columns gives equal weight to each of the sources of information.

Assembly

Assembly costs depend on the cost of labour and the time involved in assembly.

The Canadian manufacturer labour rate is $17.64 per hour (2017 Can$), as per Statistics Canada (2016), and the foreign labour rate is $2.58 per hour (2017 Can$), as per Panchal (2016). The weighted average labour rate based on the percentage of domestic (13%) and imported (87%) production is thus $4.52 per hour.

The assembly time of a CWC is based upon the number of components and associated assembly operations. The percentage increase in the number of components associated with various safer alternatives is outlined below.

| Category | Operating System | Number of Operating System Components (Low Estimate) table 2 note 1 |

Number of Operating System Components (High Estimate) table 2 note 1 |

Average Number of Operating System Components table 2 note 2 | Incremental Number of Operating System Components vs. Baseline corded system |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline corded operating system | Cord lock | 8 | 23 | 17 | |

| Continuous loop with tension device | 13 | 25 | |||

| Safer alternative (no operating cords) | Cordless (no button) | 13 | 30 | 22 | 125% |

| Cordless (button) | 16 | 30 | 23 | 133% | |

| Cordless (with tilt wand) | 18 | 30 | 24 | 139% | |

| Wand/slider | 40 | 40 | 40 | 232% | |

| Average incremental number of components: | 157% | ||||

Table 2 note(s)

|

|||||

As shown above, safe alternatives are estimated to have an average of 57% more components than a baseline corded operating system.

The assembly time of a cordless (no button) operating system module is estimated by Panchal (2016) to be 0.036 hours (129 seconds). Industry stakeholder comments indicate that some products, including those with cordless operating systems, are subject to both pre-assembly (in a low-cost foreign environment) and final assembly (in a high-cost domestic environment). Such products require additional assembly time for balancing and tuning of at least one minute, totalling 0.053 hours (190 seconds). Based on the decreased number of components of an average baseline corded operating system (Table 2), it is estimated that the average assembly time of a baseline corded operating system is 0.041 hours (147 seconds). Applying a 57% increase for assembly time to a baseline corded operating system results in an incremental assembly time for an average safer alternative operating system of 0.023 hours (84 seconds). Multiplying the incremental assembly time by the weighted average labour rate yields an incremental cost of $0.11 per unit.

Combining the incremental component cost with the incremental assembly cost yields a net incremental cost per unit of $2.92 for safer alternatives. The incremental component and assembly cost to make the 3 887 454 otherwise non-compliant units compliant is estimated to be $11.35 million.

Research and development

We assume that research and development costs will involve hiring one dedicated engineer for six months per company. We also assume that manufacturers with fewer than five employees will bear no such costs (i.e. those associated with hiring additional engineering staff) given the likelihood that they will source components rather than manufacture them. Furthermore, we assume that importers of finished products will switch to sourcing from suppliers already producing compliant window coverings, thus avoiding research and development costs.

The Canadian applied science (equivalent to engineer) labour rate is $35.67 (2017 Can$) per hour. Under the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) 33792 — Blind and shade manufacturing, Statistics Canada reports that 54.5% of Canadian window covering manufacturers have more than five employees, for a total of 107 manufacturers. Multiplying the wages of one engineer for a period of six months by 107 manufacturers yields a total estimated research and development cost of $3.98 million. This cost is counted as a one-time expense imposed by the advent of the Regulations to achieve compliance and is not considered an annual cost thereafter.

Tooling

The tooling cost is calculated by multiplying the tooling fabrication time by the toolmaking cost, taking into account the number of Canadian businesses that are estimated to assume costs associated with a tooling change.

We assume that only medium- and large-sized Canadian manufacturers (employing at least 100 employees) have the capability of fabricating all components on site. Therefore, it is estimated that 10 domestic manufacturers may assume tooling costs, consistent with comments received during the Canada Gazette, Part I, consultation and data made available by Statistics Canada (NAICS 33792).

Furthermore, we assume that the remaining small manufacturers that may source components from overseas rather than manufacture them will absorb tooling costs in their purchasing contracts. Subtracting the 10 medium- and large-sized Canadian manufacturers accounted for above from the 107 Canadian manufacturers with more than five employees results in 97 businesses subjected to overseas tooling costs.

We estimate that tooling fabrication time would be 2 000 hours per manufacturer. Panchal (2016) estimates the domestic hourly tool-fabrication cost to be $77.92 (2017 Can$), and the overseas hourly tool-fabrication cost to be $49.35 (2017 Can$). When multiplying these costs by the number of businesses subjected to domestic and overseas tooling, the total tooling cost is estimated to be $11.1 million. This cost is counted as a one-time expense imposed by the advent of the Regulations to achieve compliance and is not considered an annual cost thereafter.

Conclusion

By combining the incremental costs outlined above, we estimate the total cost to be $29.1 million in the first year of the Regulations, and $14.0 million per year thereafter, with cumulative costs of $267 million over a 20-year period.

Discounting future costs at 7% annually provides a present cost of $145 million. With present benefits of $77 million, this results in a cost-benefit ratio of 1.88. When annualized over a 20-year period, the net present value amounts to a cost of $6.4 million per year.

Distributional and gender-based analysis

The Regulations take into consideration the amount of strength that children and the elderly can apply, and have specified force requirements to allow for the operation of products without difficulty for the elderly while still providing safety to children. Specifically, the Regulations have undertaken a gender-based analysis with respect to pull forces, by considering the strongest force that a young child (male) can exert, and also the forces that an elderly female can exert. There is no additional cost associated with this issue.

The Regulations take into consideration the incident characteristics associated with CWCs. The injury pathways are the same for all children aged one to four. The Regulations help to protect young children from the strangulation hazard of long accessible cords irrespective of their size or gender. There is no additional cost associated for gender-based considerations.

Persons of short stature and persons with a disability already encounter accessibility issues with many current CWCs that require wide arm motions and cleats to secure long cords up high off the ground. To accommodate disabled persons and people of short stature, a safe product should have operating controls within reach of the user, without the need to climb. Many affordable safe window covering designs that would meet the requirements of the Regulations can meet these needs without reducing accessibility.

The Regulations apply the same requirements to all types of products. In a 2015 survey conducted by GLS Research on behalf of WCMA, low-income respondents were the most likely to have bought stock window coverings (74%), while the likelihood of buying custom window coverings increased with household income (WCMA 2015a), meaning that higher-income households would be more likely to purchase window coverings more likely to pose a strangulation risk if a market-segmentation approach was adopted.

Noting that the geography of Canada extends far into the north where the number of hours of daylight in the summer can exceed 20 hours in many northern communities, there is a clear need for window coverings to help people sleep during the summer. According to a study of residential windows and window coverings prepared for the United States Department of Energy, the great majority of window coverings (75% to 84%) are not adjusted on a given day even when segregated into summer and winter, weekday and weekend (D&R International Ltd. 2013). One possible explanation offered by the author of the study is that in the winter it is dark when people wake up and dark when they return home from work, so there is no reason to adjust window coverings. Similarly, in northern climates when it is light for almost the entire day during the summer, there is no need to adjust window coverings. That is to say, the operating systems of window coverings are rarely engaged to raise or lower the blind. With this in mind, the Regulations have no additional effect on the people of northern territories, which are also home to a large population of Indigenous people: 53% of the combined population of Nunavut, Northwest Territories, and Yukon identify as Aboriginal (Statistics Canada 2016).

Sensitivity and uncertainty in the costs and benefits

Sensitivity analyses have been conducted for the baseline, costs, benefits and additional aspects of the cost-benefit analysis. For each sensitivity that generates a dollar value, a resulting cost-benefit ratio has been calculated. The highest cost scenario of the sensitivity analysis yields a cost-benefit ratio of 2.29. At the opposite end of the spectrum, a scenario for which benefits exceed costs at a ratio of 1.26 has been calculated.

Baseline sensitivity

Remaining risk

This analysis assumes that, without the Regulations, the manufacture, import, and sale of CWCs in Canada would comply with the provisions of the new American voluntary standard beginning in 2019. This analysis also assumes that the Canadian market consists of 75% stock and 25% custom products. Furthermore, voluntary compliance with the new American voluntary standard will eliminate the risk of strangulation for operating cords of stock products and have no impact on the risk associated with the operating cords of custom products and the inner cords of both stock and custom products. As a result, the remaining risk for the baseline scenario has been estimated to be 40% of the historic risk.

Comments received from industry stakeholders during public consultations suggest that cordless custom products presently make up between 5% and 10% of the total window covering product market, and therefore, the remaining risk should be reduced. If the remaining risk that would be affected by the Regulations is 30% rather than 40%, the value of the benefits of lives saved would decrease to $18.2 million, resulting in total benefits valued at $71 million over the next 20 years (2017 price level, discounted at 7%). Correspondingly, the number of units affected by the Regulations would decrease, lowering the costs associated with the manufacturing of components and with assembly costs. Total costs associated with a reduced remaining risk would be decreased to $112 million over the next 20 years (2017 price level, discounted at 7%). The resulting cost-benefit ratio would be 1.57.

Rate of compliance with the new American voluntary standard

With respect to the effectiveness of the new American voluntary standard in reducing strangulations, the baseline scenario of the cost-benefit analysis assumes 100% of products will comply with its provisions.

Compliance with the new American voluntary standard is entirely voluntary, and there is no organization or agency that purports to monitor or enforce compliance with its requirements.

In 2015 and 2017, Health Canada conducted compliance and enforcement projects under the CWCPR which incorporates by reference the Canadian national standard (the requirements of which are aligned with the 2012 version of the American voluntary standard). In 2015, 3 out of 21 products (14%) sampled from the Canadian market were recalled for non-compliance that posed a strangulation hazard. In 2017, 2 out of 19 products (11%) were recalled for non-compliance that posed a strangulation hazard. Based on these recent market compliance projects, less than 100% compliance with the new American voluntary standard may be expected in the baseline. This would result in a higher remaining risk of strangulation that the Regulations would impact, resulting in increased benefits and costs.

Cost sensitivity and uncertainty

This analysis includes only the costs associated with manufacturing (component costs and assembly costs), research and development, and tooling, and accounting for the impact of price changes on quantities sold. Based on the comments received during the Canada Gazette, Part I, consultation and the principal statistics related to manufacturing expenses for blind and shade manufacturing as per Statistics Canada (NAICS 33792), these costs are understood to comprise the vast majority of incremental costs that can be attributed to the Regulations. Potential costs related to stranded inventory, which was a noted concern of respondents to the Canada Gazette, Part I, consultation, are accounted for in the small business lens calculations and addressed by an extended coming-into-force period.

This analysis does not account for potential costs related to the licensing of technology (royalties), restrictions due to existing patents, and training of personnel on new products. When weighed against the incremental costs to manufacture a compliant product that were included in the analysis, which are noted to comprise the vast majority of incremental costs in the breakdown of expenses by Statistics Canada, these potential costs are considered to have a minimal impact on the cost estimates.

Comments from industry stakeholders indicated that, while most large manufacturers would choose to develop their own technology, smaller manufacturers who license technology may be faced with having to pay royalties of approximately 5% of product costs. Further comments suggested that these costs could be offset by savings related to parts obsolescence and faster assembly time.

High-end unit costs

This analysis takes into account a broad range of products available in the market that are generally available in higher volumes. While the source data for component and assembly costs considered both inexpensive (low end) and expensive (high end) window covering designs, the costs associated with low volume customized window coverings, or products incorporating much higher quality components, would increase the overall costs for those smaller segments of the market.

In consideration of the increased cost for low volume, customized, expensive window coverings and higher quality components, Industrial Economics, Incorporated (2017) estimates a high-end scenario unit cost increase of approximately 20%. A sensitivity analysis that increases the estimate of costs by 20% results in costs valued at $174 million over the next 20 years (2017 price level, discounted at 7%). The resulting cost-benefit ratio would be 2.26.

Research and development

This analysis included research and development costs for all Canadian window covering manufacturers that have more than five employees, for a total of 107 manufacturers. Comments received from industry stakeholders during public consultations suggested that the vast majority of small window covering businesses (who rely on large manufacturers for components) are not spending on research and development. Further comments indicated that most medium- and large-sized manufacturers already have cordless products in their lineup and so research and development costs would be reduced. Conversely, a comment from an industry stakeholder suggested that research and development costs should be increased by a factor of 10 to account for additional development and product validation activities, as well as preparation of facilities and suppliers.