Vol. 149, No. 10 — May 20, 2015

Registration

SOR/2015-100 May 1, 2015

TRANSPORTATION OF DANGEROUS GOODS ACT, 1992

Regulations Amending the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Regulations (TC 117 Tank Cars)

P.C. 2015-486 April 30, 2015

His Excellency the Governor General in Council, on the recommendation of the Minister of Transport, pursuant to section 27 (see footnote a) of the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Act, 1992 (see footnote b), makes the annexed Regulations Amending the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Regulations (TC 117 Tank Cars).

REGULATIONS AMENDING THE TRANSPORTATION OF DANGEROUS GOODS REGULATIONS (TC 117 TANK CARS)

AMENDMENTS

1. The portion of section 1.34 of the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Regulations (see footnote 1) after the title is replaced by the following:

- (1) Despite section 6.1 of the Act and section 4.2 of Part 4 (Dangerous Goods Safety Marks) of these Regulations, substances that have a flash point greater than 60°C but less than or equal to 93°C may be transported on a road vehicle, on a railway vehicle or on a ship on a domestic voyage as Class 3, Flammable Liquids, Packing Group III. In that case, and subject to subsection (2), the requirements of these Regulations that relate to flammable liquids that have a flash point less than or equal to 60°C must be complied with.

- (2) When substances that have a flash point greater than 60°C but less than or equal to 93°C are transported in accordance with subsection (1), sections 5.14.1 to 5.15.6 and 5.15.11 of Part 5 (Means of Containment) do not apply in respect of a railway vehicle that transports the substances, and an emergency response assistance plan is not required for the substances under subsection 7.1(6) of Part 7 (Emergency Response Assistance Plan).

2. (1) The Table of Contents of Part 5 of the Regulations is amended by striking out the entry for section 5.5.1.

(2) The Table of Contents of Part 5 of the Regulations is amended by adding the following after the entry for section 5.14:

Tank Cars for Flammable Liquids

- Clause 10.5.3 of TP14877........................................................5.14.1

- Clause 10.1 of TP14877 – May 1, 2017.......................................5.14.2

- Clause 10.1 of TP14877 – May 1, 2025.......................................5.14.3

- Tank Car Selection – May 1, 2017.............................................5.15

- Tank Car Selection – March 1, 2018..........................................5.15.1

- Tank Car Selection – April 1, 2020............................................5.15.2

- Tank Car Selection – May 1, 2023.............................................5.15.3

- Tank Car Selection – July 1, 2023.............................................5.15.4

- Tank Car Selection – July 1, 2025.............................................5.15.5

- Tank Cars Manufactured on or after October 1, 2015...................5.15.6

- Enhanced Class 111 Tank Cars.................................................5.15.7

- TC 117R Tank Cars.................................................................5.15.8

- TC 117 Tank Cars..................................................................5.15.9

- TC 117P Tank Cars................................................................5.15.10

- Reporting.............................................................................5.15.11

3. Section 5.5.1 of the Regulations is repealed.

4. Section 5.14 of the Regulations is amended by adding the following after subsection (1):

(1.1) If there is a conflict between sections 5.14.1 to 5.15.6 and subparagraph (1)(b)(ii), sections 5.14.1 to 5.15.6 prevail to the extent of the conflict.

5. Part 5 of the Regulations is amended by adding the following after section 5.14:

Tank Cars for Flammable Liquids

5.14.1 Clause 10.5.3 of TP14877

The requirements of clause 10.5.3 of TP14877 do not apply in respect of the importing, offering for transport, handling or transporting of any dangerous goods included in Class 3, Flammable Liquids, Packing Group I, II or III, in a tank car.

5.14.2 Clause 10.1 of TP14877 – May 1, 2017

Starting on May 1, 2017, the exception set out in clause 10.1 of TP14877 does not apply in respect of the importing, offering for transport, handling or transporting of any of the following dangerous goods in a tank car:

- (a) UN1170, ETHANOL more than 24% ethanol, by volume;

- (b) UN1267, PETROLEUM CRUDE OIL;

- (c) UN1268, PETROLEUM DISTILLATES, N.O.S., or PETROLEUM PRODUCTS, N.O.S.;

- (d) UN1987, ALCOHOLS, N.O.S.;

- (e) UN1993, FLAMMABLE LIQUID, N.O.S.;

- (f) UN3475, ETHANOL AND GASOLINE MIXTURE with more than 10% ethanol, ETHANOL AND MOTOR SPIRIT MIXTURE with more than 10% ethanol, or ETHANOL AND PETROL MIXTURE with more than 10% ethanol; and

- (g) UN3494, PETROLEUM SOUR CRUDE OIL, FLAMMABLE, TOXIC.

5.14.3 Clause 10.1 of TP14877 – May 1, 2025

Starting on May 1, 2025, the exception set out in clause 10.1 of TP14877 does not apply in respect of the importing, offering for transport, handling or transporting of dangerous goods included in Class 3, Flammable Liquids, Packing Group I, II or III, in a tank car.

5.15 Tank Car Selection – May 1, 2017

(1) Starting on May 1, 2017, a person must not import, offer for transport, handle or transport any of the dangerous goods listed in subsection (2) and included in Packing Group I, II or III in a tank car unless the tank car

- (a) is a Class 105, 111, 112, 115 or 120 tank car that is in compliance with the requirements of TP14877 for the tank car’s class and that is equipped with a jacket that

- (i) is made of ASTM A1011 steel, or steel of an equivalent standard,

- (ii) has a thickness equal to or greater than 3 mm (11 gauge), and

- (iii) is weather-resistant;

- (b) is an enhanced Class 111 tank car with a jacket;

- (c) is an enhanced Class 111 tank car without a jacket;

- (d) is a TC 117R tank car;

- (e) is a TC 117 tank car; or

- (f) is a TC 117P tank car.

(2) The dangerous goods are

- (a) UN1267, PETROLEUM CRUDE OIL;

- (b) UN1268, PETROLEUM DISTILLATES, N.O.S., or PETROLEUM PRODUCTS, N.O.S.; and

- (c) UN3494, PETROLEUM SOUR CRUDE OIL, FLAMMABLE, TOXIC.

5.15.1 Tank Car Selection – March 1, 2018

(1) Starting on March 1, 2018, a person must not import, offer for transport, handle or transport any of the dangerous goods listed in subsection (2) and included in Packing Group I, II or III in a tank car unless the tank car

- (a) is an enhanced Class 111 tank car with a jacket;

- (b) is an enhanced Class 111 tank car without a jacket;

- (c) is a TC 117R tank car;

- (d) is a TC 117 tank car; or

- (e) is a TC 117P tank car.

(2) The dangerous goods are

- (a) UN1267, PETROLEUM CRUDE OIL;

- (b) UN1268, PETROLEUM DISTILLATES, N.O.S., or PETROLEUM PRODUCTS, N.O.S.; and

- (c) UN3494, PETROLEUM SOUR CRUDE OIL, FLAMMABLE, TOXIC.

5.15.2 Tank Car Selection – April 1, 2020

(1) Starting on April 1, 2020, a person must not import, offer for transport, handle or transport any of the dangerous goods listed in subsection (2) and included in Packing Group I, II or III in a tank car unless the tank car

- (a) is an enhanced Class 111 tank car with a jacket;

- (b) is a TC 117R tank car;

- (c) is a TC 117 tank car; or

- (d) is a TC 117P tank car.

(2) The dangerous goods are

- (a) UN1267, PETROLEUM CRUDE OIL;

- (b) UN1268, PETROLEUM DISTILLATES, N.O.S., or PETROLEUM PRODUCTS, N.O.S.; and

- (c) UN3494, PETROLEUM SOUR CRUDE OIL, FLAMMABLE, TOXIC.

5.15.3 Tank Car Selection – May 1, 2023

(1) Starting on May 1, 2023, a person must not import, offer for transport, handle or transport any of the dangerous goods listed in subsection (2) and included in Packing Group I, II or III in a tank car unless the tank car

- (a) is an enhanced Class 111 tank car with a jacket;

- (b) is an enhanced Class 111 tank car without a jacket;

- (c) is a TC 117R tank car;

- (d) is a TC 117 tank car; or

- (e) is a TC 117P tank car.

(2) The dangerous goods are

- (a) UN1170, ETHANOL more than 24% ethanol, by volume;

- (b) UN1987, ALCOHOLS, N.O.S.;

- (c) UN1993, FLAMMABLE LIQUID, N.O.S.; and

- (d) UN3475, ETHANOL AND GASOLINE MIXTURE with more than 10% ethanol, ETHANOL AND MOTOR SPIRIT MIXTURE with more than 10% ethanol, or ETHANOL AND PETROL MIXTURE with more than 10% ethanol.

5.15.4 Tank Car Selection – July 1, 2023

(1) Starting on July 1, 2023, a person must not import, offer for transport, handle or transport any of the dangerous goods listed in subsection (2) and included in Packing Group I, II or III in a tank car unless the tank car

- (a) is an enhanced Class 111 tank car with a jacket;

- (b) is a TC 117R tank car;

- (c) is a TC 117 tank car; or

- (d) is a TC 117P tank car.

(2) The dangerous goods are

- (a) UN1170, ETHANOL more than 24% ethanol, by volume;

- (b) UN1987, ALCOHOLS, N.O.S.;

- (c) UN1993, FLAMMABLE LIQUID, N.O.S.; and

- (d) UN3475, ETHANOL AND GASOLINE MIXTURE with more than 10% ethanol, ETHANOL AND MOTOR SPIRIT MIXTURE with more than 10% ethanol, or ETHANOL AND PETROL MIXTURE with more than 10% ethanol.

5.15.5 Tank Car Selection – May 1, 2025

Starting on May 1, 2025, a person must not import, offer for transport, handle or transport dangerous goods included in Class 3, Flammable Liquids, Packing Group I, II or III, in a tank car unless the tank car

- (a) is a TC 117R tank car;

- (b) is a TC 117 tank car; or

- (c) is a TC 117P tank car.

5.15.6 Tank Cars Manufactured on or after October 1, 2015

A person must not import, offer for transport, handle or transport dangerous goods included in Class 3, Flammable Liquids, Packing Group I, II or III, in a tank car that is manufactured on or after October 1, 2015 unless the tank car

- (a) is a TC 117 tank car; or

- (b) is a TC 117P tank car.

5.15.7 Enhanced Class 111 Tank Cars

(1) For the purposes of sections 5.15 to 5.15.4 and 5.15.11, a tank car is an enhanced Class 111 tank car with a jacket if the following conditions are met:

- (a) the tank car is in compliance with the requirements of TP14877 for Class 111 tank cars;

- (b) all the top shell service equipment is enclosed in a protective housing that meets the requirements set out in subsection (3);

- (c) the tank shell and heads are made of carbon or low-alloy steel plate, in the normalized condition, that is AAR TC128 Grade B steel or ASTM A516 Grade 70 steel;

- (d) the tank heads are normalized after forming;

- (e) in the case of a tank shell and heads made of AAR TC128 Grade B steel, the shell and heads have a thickness equal to or greater than 11.1 mm (7/16 in.);

- (f) in the case of a tank shell and heads made of ASTM A516 Grade 70 steel, the shell and heads have a thickness equal to or greater than 12.7 mm (1/2 in.);

- (g) the tank car is equipped with a jacket that

- (i) is made of ASTM A1011 steel, or steel of an equivalent standard,

- (ii) has a thickness equal to or greater than 3 mm (11 gauge), and

- (iii) is weather-resistant;

- (h) the tank is insulated, or fitted with a thermal protection blanket;

- (i) the tank car is equipped with one or more reclosing pressure relief devices, each with a start-to-discharge pressure that is equal to or greater than 517 kPa (75 psi);

- (j) the tank car is equipped at each end with a head shield that

- (i) is made with structural or pressure vessel steel plate that has a thickness equal to or greater than 12.7 mm (1/2 in.), and

- (ii) covers at least the lower half of the tank head; and

- (k) in the case of a tank car equipped with a bottom outlet valve, the valve handle – unless stowed separately – is designed to bend or break free on impact without the valve opening or is designed so that all of the handle is located within the bottom discontinuity protective structure.

(2) For the purposes of sections 5.15 to 5.15.3 and 5.15.11, a tank car is an enhanced Class 111 tank car without a jacket if the following conditions are met:

- (a) the tank car meets the conditions set out in paragraphs (1)(a) to (d) and (i) to (k);

- (b) in the case of a tank shell and heads made of AAR TC128 Grade B steel, the shell and heads have a thickness equal to or greater than 12.7 mm (1/2 in.); and

- (c) in the case of a shell and heads made of ASTM A516 Grade 70 steel, the shell and heads have a thickness equal to or greater than 14.3 mm (9/16 in.).

(3) The protective housing must be in compliance with clause 10.5.3.1 of TP14877, but

- (a) clause 10.5.3.1.a must be read as “W is defined as the designed gross rail load of the tank car, less trucks”; and

- (b) clause 10.5.3.1.3 must be read as “The protective structure must provide a means of drainage with a minimum flow area equivalent to six holes, each with a diameter of 25.4 mm (1 in.)”.

5.15.8 TC 117R Tank Cars

For the purposes of sections 5.15 to 5.15.5 and 5.15.11, a tank car is a TC 117R tank car if the following conditions are met:

- (a) the tank car is in compliance with the requirements of TP14877 for Class 111 tank cars;

- (b) the tank shell and heads have a thickness equal to or greater than 11.1 mm (7/16 in.);

- (c) the tank car is equipped with a jacket that

- (i) is made of ASTM A1011 steel, or steel of an equivalent standard,

- (ii) has a thickness equal to or greater than 3 mm (11 gauge), and

- (iii) is weather-resistant;

- (d) the tank car is equipped with a thermal protection system that meets the requirements of clause 8.2.7 of TP14877;

- (e) the tank car is equipped at both ends with a full head shield that is made with structural or pressure vessel steel plate that has a thickness equal to or greater than 12.7 mm (1/2 in.);

- (f) in the case of a tank car equipped with a bottom outlet valve, the valve handle – unless stowed separately – is designed to bend or break free on impact without the valve opening or is designed so that all of the handle is located within the bottom discontinuity protective structure; and

- (g) the tank car is equipped with a reclosing pressure relief device.

5.15.9 TC 117 Tank Cars

(1) For the purposes of sections 5.15 to 5.15.6, a tank car is a TC 117 tank car if the following conditions are met:

- (a) the tank car is in compliance with the requirements of sections 1 to 9 of TP14877 for Class 111 tank cars;

- (b) the tank shell and heads are made of steel plate, in the normalized condition, that is AAR TC128 Grade B steel that

- (i) has a minimum tensile strength equal to or greater than 560 MPa (81 000 psi), and

- (ii) has a thickness equal to or greater than 14.3 mm (9/16 in.);

- (c) the plate thickness of the tank heads is measured after the heads are formed;

- (d) all the top shell service equipment – except for a hinged and bolted manway – is mounted on the manway cover plate and enclosed in a protective housing that meets the requirements set out in subsection (2);

- (e) in the case of a tank car equipped with a bottom outlet valve, the valve handle – unless stowed separately – is designed to bend or break free on impact without the valve opening or is designed so that all of the handle is located within the bottom discontinuity protective structure;

- (f) the tank car is equipped with a reclosing pressure relief device;

- (g) the tank car is equipped with a jacket that

- (i) is made of ASTM A1011 steel, or steel of an equivalent standard,

- (ii) has a thickness equal to or greater than 3 mm (11 gauge), and

- (iii) is weather-resistant;

- (h) the tank car is equipped with a thermal protection system that meets the requirements of clause 8.2.7 of TP14877;

- (i) the tank car is equipped with a tank head puncture resistance system that meets the requirement of clause 8.2.8 of TP14877;

- (j) the test pressure of the tank is 6.9 bar (100 psi); and

- (k) the burst pressure of the tank is 34.5 bar (500 psi).

(2) The protective housing must be in compliance with clause 10.5.3.1 of TP14877, but

- (a) clause 10.5.3.1.a must be read as “W is defined as the designed gross rail load of the tank car, less trucks”; and

- (b) clause 10.5.3.1.3 must be read as “The protective structure must provide a means of drainage with a minimum flow area equivalent to six holes, each with a diameter of 25.4 mm (1 in.)”.

5.15.10 TC 117P Tank Cars

(1) For the purposes of sections 5.15 to 5.15.5 and 5.15.11, a tank car is a TC 117P tank car if the tank car passes a side impact test and a head impact test carried out in accordance with this section and meets the conditions set out in

- (a) paragraphs 5.15.8(a), (d), (f) and (g); or

- (b) paragraphs 5.15.9(1)(a), (d) to (f), (h), (j) and (k).

(2) For the purposes of section 5.15.6, a tank car is a TC 117P tank car if the tank car passes a side impact test and a head impact test carried out in accordance with this section and meets the conditions set out in paragraphs 5.15.9(1)(a), (d) to (f), (h), (j) and (k).

(3) A tank car passes the impact tests if, at rest, there is no leak visible from the tank shell or head within at least one hour of the side impact test and within at least one hour of the head impact test.

(4) The side impact test is carried out as follows:

- (a) the tank car is restrained in the direction of impact;

- (b) the tank is filled, with no more than 4 per cent outage and with no internal pressure, with lading of the same density as the dangerous goods that the tank car is intended to carry;

- (c) the tank may be filled with water if the dangerous goods that the tank car is intended to carry have a specific gravity of 1.1 or less;

- (d) the tank car is hit by a proxy object;

- (e) the proxy object has a mass equal to or greater than 129 727 kg (286,000 lbs.) and is fitted with a rigid punch that

- (i) protrudes at least 1.5 m (60 in.) from the base of the proxy object, and

- (ii) has a cross-section 30.5 cm (12 in.) high by 30.5 cm (12 in.) wide, with a 2.54 cm (1 in.) radius on each edge of the impact face;

The proxy object is intended to approximate a loaded freight car, including the coupler with the knuckle removed.

- (f) at the instant of impact,

- (i) the centre of the impact face of the punch is aligned with the intersection of the vertical and longitudinal centrelines of the tank, and

- (ii) the horizontal centreline of the punch is perpendicular to the point of impact; and

- (g) at the instant of impact, the speed of the punch face is equal to or greater than 5.36 m/s (12 mph).

(5) The head impact test is carried out as follows:

- (a) the tank car is restrained in the direction of impact;

- (b) the tank is filled, with no more than 4 per cent outage and with no internal pressure, with lading of the same density as the dangerous goods that the tank car is intended to carry;

- (c) the tank may be filled with water if the dangerous goods that the tank car is intended to carry have a specific gravity of 1.1 or less;

- (d) the tank car is hit by a proxy object;

- (e) the proxy object has a mass equal to or greater than 129 727 kg (286,000 lbs.) and is fitted with a rigid punch that

- (i) protrudes at least 1.5 m (60 in.) from the base of the proxy object, and

- (ii) has a cross-section 30.5 cm (12 in.) high by 30.5 cm (12 in.) wide, with a 2.54 cm (1 in.) radius on each edge of the impact face;

The proxy object is intended to approximate a loaded freight car, including the coupler with the knuckle removed.

- (f) at the instant of impact,

- (i) the centre of the impact face of the punch is aligned with the centre of the tank head, and

- (ii) the horizontal centreline of the punch is perpendicular to the point of impact; and

- (g) at the instant of impact, the speed of the punch face is equal to or greater than 8.05 m/s (18 mph).

5.15.11 Reporting

Starting on January 1, 2017, a consignor must, on reasonable notice given by the Minister, provide the Minister with the following information:

- (a) the number of TC117R tank cars that the consignor owns or leases;

- (b) the number of TC117P tank cars that the consignor owns or leases;

- (c) the number of Class 111 tank cars that the consignor owns or leases, and uses for importing, offering for transport or handling dangerous goods included in Class 3, Flammable Liquids; and

- (d) the number of enhanced Class 111 tank cars that the consignor owns or leases, and uses for importing, offering for transport or handling dangerous goods included in Class 3, Flammable Liquids.

6. The portion of subsection 7.1(6) of the Regulations before paragraph (a) is replaced by the following:

- (6) A person who imports or offers for transport any of the following dangerous goods by rail in a tank car must have an approved ERAP if the quantity of the dangerous goods in the tank car exceeds 10 000 L:

7. The portion of UN Numbers UN1170, UN1202, UN1203, UN1267, UN1268, UN1863, UN1987, UN1993, UN3295, UN3475 and UN3494 of Schedule 1 to the Regulations in columns 5 and 7 is replaced by the following:

| Col. 1 | Col. 5 | Col. 7 |

|---|---|---|

| UN Number | Special Provisions | ERAP Index |

| UN1170 | 150 | |

| 150 | ||

| UN1202 | 88, 91, 150 | |

| UN1203 | 17, 88, 91, 98, 150 | |

| UN1267 | 92, 106, 150 | |

| 92, 106, 150 | ||

| 92, 106, 150 | ||

| UN1268 | 92, 150 | |

| 91, 92, 150 | ||

| 91, 92, 150 | ||

| UN1863 | 17, 150 | |

| 17, 91, 150 | ||

| 17, 91, 150 | ||

| UN1987 | 16, 150 | |

| 16, 150 | ||

| UN1993 | 16, 150 | |

| 16, 150 | ||

| 16, 150 | ||

| UN3295 | 150 | |

| 150 | ||

| 150 | ||

| UN3475 | 150 | |

| UN3494 | 150 | |

| 150 | ||

| 150 |

8. Schedule 2 to the Regulations is amended by adding the following after special provision 149:

- 150

- An emergency response assistance plan (ERAP) is required for these dangerous goods under subsection 7.1(6) of Part 7 (Emergency Response Assistance Plan).

- UN1170, UN1202, UN1203, UN1267, UN1268, UN1863, UN1987, UN1993, UN3295, UN3475, UN3494

TRANSITIONAL PROVISION

9. A person may, for a period of six months that begins on the day on which these Regulations come into force, comply with the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Regulations as they read immediately before that day.

COMING INTO FORCE

10. These Regulations come into force on the day on which they are published in the Canada Gazette, Part II.

REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS STATEMENT

(This statement is not part of the Regulations.)

Executive summary

Issues: North America has been experiencing a significant increase in crude oil supply and other flammable liquids, such as ethanol, and in many cases, this has resulted in a corresponding increase in the transportation of these liquids by rail. Following the tragic accident in Lac-Mégantic on July 6, 2013, the Transportation Safety Board (TSB) launched an investigation into the causal and contributing factors of the accident.

On January 23, 2014, the Transportation Safety Board released three interim recommendations. One was specific to the TC/DOT 111 tank car used to transport crude oil. It recommended that

The Department of Transport [Transport Canada] and the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration require that all Class 111 tank cars used to transport flammable liquids meet enhanced protection standards that significantly reduce the risk of product loss when these cars are involved in an accident.

The Transportation Safety Board has publicly indicated that TC/DOT 111 tank cars, in addition to the newly adopted TP14877/CPC 1232 standard in Canada, are not sufficiently crash resistant and/or robust to withstand the forces in an accident, which leads to a significant risk of tank car failure and release of dangerous goods during an incident.

Description: These amendments to the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Regulations (TDGR) introduce specifications for a new class of tank car for flammable liquid dangerous goods service and require rail tank cars destined for flammable liquid service (e.g. crude oil, ethanol, gasoline, diesel fuel, and aviation fuel) to be built to these specifications.

These amendments also establish retrofit requirements for older TC/DOT 111 tank cars and the enhanced Class 111 tank car (TP14877/CPC 1232). Finally, it entrenches in regulation the Minister of Transport’s announcement of April 23, 2014, in response to the Transportation Safety Board’s interim recommendations to phase out or retrofit older TC/DOT 111 tank cars, and prescribes retrofit requirements for the TP14877/ CPC 1232 tank cars used to transport crude, ethanol and other flammable liquids.

The new standard requires thicker steel, full head shield protection, a jacket with thermal protection, top-fitting protection, and new bottom outlet requirements.

Cost-benefit statement: The present value of the total costs for the Regulations is estimated to be $1 billion over 20 years.

A typical derailment costs an estimated $13,197,000. Therefore, only 3.8 incidents per year (or a total of 76 typical railway incidents over the 20 years) would need to be prevented for benefits of these Regulations to equal its estimated costs. In 2013, there were 7 incidents reported to Transport Canada. There have been another 11 incidents reported to Transport Canada in 2014.

Alternatively, in the case of a catastrophic incident, like the Lac-Mégantic tragedy, preventing one such incident would equal the costs for these Regulations.

Because of the recent exponential increase in demand for flammable liquid by rail, especially for crude oil and ethanol, it is expected that the benefits of the Regulations for preventing the release of flammable liquids or minimizing the consequences of spills and/or pool fires will likely exceed the estimated costs. Environmental damage resulting from derailments involving the release of flammable liquids would also be avoided to a significant degree, thereby leading to further economic and environmental benefits over time.

“One-for-One” Rule and small business lens: The “One-for-One” Rule does not apply, as it does not introduce any new administrative burden on industry. The small business lens does not apply to these Regulations, as there are no small businesses directly affected.

Domestic and international coordination and cooperation: The Department of Transport (Transport Canada) has worked with Industry and United States (U.S.) regulators to bring forward an appropriate tank car, retrofit requirement and timeline that is harmonized, to the maximum extent possible, with a potential U.S. final rule. Regulatory harmonization between Canada and the U.S. is important as these tank cars travel across Canadian/U.S. borders on a daily basis.

During the development of this regulatory proposal, Transport Canada has had ongoing technical discussions with its U.S. regulatory colleagues from the Federal Railway Administration (FRA) and the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA). Transport Canada also had ongoing discussions with key industry stakeholders as it developed this regulatory proposal.

Background

North America has been experiencing a significant increase in crude oil supply, bolstered both by growing production in the Canadian oil sands, limited pipeline capacity and the recent expansion of shale oil and natural gas production in the U.S. and Canada. This has also coincided with the shift to ethanol production in North America in the mid to late 1990s and the subsequent significant increase in surface transport of ethanol.

North American ethanol production or shale oil and natural gas extraction has been mostly in geographic areas not linked to traditional crude oil or natural gas pipelines, resulting in an exponential increase in the transport of these flammable liquid dangerous goods by surface transport.

Moreover, surface transport of crude oil and ethanol has enabled industry to maximize the value of these resources and to utilize refinery capacity more efficiently across North America.

For most of 2014, world crude oil prices have been above US$100 a barrel. In late 2014, crude oil prices fell dramatically to below US$50 a barrel. Crude oil price has, throughout its commodities life cycle, fluctuated to reflect demand and supply. Low priced cycles have traditionally led to a correction in the market place from reduced capital spending on new projects through to a further reduction in supply or increased demand leading to a recovery in its price.

Up to December 2014, the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP) had been forecasting that crude oil volumes transported in Canada by rail would increase from about 200 000 barrels per day (b/d) in late 2013 to 700 000 b/d by the end of 2016. Also, shippers in the U.S. Bakken Formation region (excluding the Canadian Bakken Formation) have added 400 000 b/d of rail loading capacity in 2013, and have undertaken projects that would add more than 500 000 b/d in 2014. Rail loading and off-loading facilities have been constructed throughout the U.S. at a similar pace over the past two years. In 2012 and 2013, over 700 000 b/d of loading capacity was added in the Bakken Formation, and over 800 000 b/d of off-loading capacity was added on the East Coast.

Canadian oil production growth has been driven by the oil sands, which was expected to grow 2.5 times from its current production of 1.9 million b/d to 4.8 million b/d by 2030. Total conventional production, inclusive of condensate (a low-density mixture of hydrocarbons that are present as gaseous components used to dilute heavy oil for transport by pipeline or rail), grows slightly and would contribute 1.5 million b/d to total production. This was a reversal of the declining trend in condensate production previously forecast by CAPP.

On January 21, 2015, following a short-term review of its industry forecast following the steep decline in oil prices, CAPP indicated that the long-term need for Canada to diversify its oil and gas markets and build infrastructure to move these products to market remained strong despite the recent sharp decline in oil prices and cuts in capital spending intentions.

Industry also indicated that demand from global markets, such as Asia and Europe, would also increase the rail transport of crude oil to ports for transport by sea to markets overseas. Adding to the increased usage of rail is the extension of the timelines associated for new pipeline capacity to enter the market.

According to CAPP, the U.S. Atlantic seaboard and eastern Canada markets represented over 2 million b/d of crude oil demand. Since these refineries have limited access to North American crude oil by pipelines, the transport of crude oil by rail to service these markets have grown exponentially over the last five years. The U.S. Gulf Coast remains the current largest destination for Canadian crude oil using many different modes of transport, including rail and pipeline. Transport of crude oil by rail is expected to remain an important mode of transport to enable Canadian crude to reach its markets over the coming years.

With this exponential increase in the transportation of flammable liquids, particularly for crude oil and ethanol, Canada can expect to experience an increase in rail incidents involving crude oil and ethanol. In 2013, 144 rail incidents involved dangerous goods (import, handling and transport) in Canada, up from 119 in 2012 and up from the five-year average of 133. Seven accidents resulted in a dangerous goods release in 2013, compared to 2 in 2012, and the five-year average of 3. Five of the 7 accidents involved crude oil. Seven incidents in 2013, and another 11 incidents in 2014 were related directly to a release from the means of containment during the transport of crude oil and ethanol by rail.

This increase is consistent with an increase in shipments of crude oil by rail from 500 car loads in 2009 to 160 000 car loads in 2013. With the significant increase in shipments by rail, even with a similar rate of rail incidents, the number of derailments involving a train carrying crude oil will likely increase along with the number of releases of dangerous goods. According to CAPP, following a return to a more normal price range for crude oil, Canadian crude oil production is expected to grow over the long term to 6.4 million b/d by 2030. These supplies are intended to meet the demand of markets located throughout North America and overseas.

The worst rail incident in Canadian history involving flammable liquids occurred on July 6, 2013. On that day a train carrying 72 tank cars of crude oil derailed at over 100 km/h in the town of Lac-Mégantic. Almost all of the derailed tank cars were damaged, and many had large breaches. About six million litres of crude oil was quickly released. According to the Transportation Safety Board of Canada, a fire began almost immediately and the massive pool fire that ensued left 47 people dead. Another 2 000 people were forced from their homes, and much of the downtown core of Lac-Mégantic was destroyed. All of the rail cars involved in this tragedy were TC/DOT 111 tank cars.

There are currently about 147 000 TC/DOT 111 tank cars in North American flammable liquids service. About 80 000 of these tank cars were built prior to 2011. There are still about 7 500 TP14877/CPC 1232 jacketed tank cars estimated to be constructed for crude oil service in 2015. By the end of 2015, it is expected that about 115 000 of these tank cars will be used for the transport of crude oil and ethanol.

According to industry, most crude oil transported by rail in the U.S. originates on U.S. or Canadian Class 1 railroads (which includes the Canadian National Railway Company [CN] and the Canadian Pacific Railway Limited [CPR]). Crude oil delivered by rail in the U.S. reached almost 234 000 carloads in 2012. In 2013, the number of carloads increased significantly to over 400 000. In Canada, the scale of crude oil transportation by rail is smaller, but similar to the U.S. in terms of strong growth. By December 2013, the number of carloads in Canada reached over 16 000 per month. Although the price of crude has fallen dramatically in the later part of 2014 and early 2015, industry has indicated to Transport Canada that current levels of crude oil by rail continue although the rate of growth may slow until price per barrel returns to more normal levels.

Under the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Act, 1992, the purpose of Transport Canada’s Transport Dangerous Goods Directorate is the promotion of public safety during the transport of dangerous goods. To help accomplish this, the Transport of Dangerous Goods Regulations (TDGR) include requirements for the manufacture and use of means of containment for the handling, offering for transport, importing and transporting of dangerous goods primarily by referencing safety standards.

The TDGR groups dangerous goods into nine classes (e.g. flammable liquids, explosives, radioactive materials). Flammable liquids are then subdivided into one of three “packing groups,” depending on their risk factors (boiling point and flash point), where Packing Group I represents the highest risk and Packing Group III the lowest.

Transport Canada develops, in collaboration with standards-developing organizations accredited by the Standards Council of Canada (SCC), safety standards that are incorporated by reference in the TDGR. The TDGR also incorporate by reference international recommendations, such as the United Nations Recommendations, the International Maritime Dangerous Goods Code and the International Civil Aviation Organization Technical Instructions.

Currently, the TDGR incorporate by reference tank car standards for the selection and use by rail of flammable liquids. These standards were published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, on July 2, 2014, bringing into force the 2011 consensus standard (commonly referred to as a CPC 1232 tank car in the U.S.) developed through the American Association of Railroads (AAR) Tank Car Committee.

Industry had been voluntarily building new tank cars to the requirements of CPC-1232 - Requirements for Cars Built for the Transportation of Packing Group I and II Materials with the Proper Shipping Names “Petroleum Crude Oil”,“Alcohols, n.o.s.” and “Ethanol and Gasoline Mixture”, which are similar to requirements now in force under the safety standard TP14877.

The TP14877 standard was expanded in Canada to include transport of petroleum crude oil classified under Packing Group III in addition to the requirements under the CPC 1232 circular, which were designed for petroleum crude oil included in Packing Group I and II for newly manufactured tank cars. Over 58 000 of these tank cars have been ordered since 2011 for the transport of crude oil and ethanol. The last of these ordered tank cars (about 7 500) are expected to all be delivered in 2015.

TC/DOT 111 tank cars built to this standard include thicker steel, half head shields, top-fitting protection and the use of normalized steel. There are several variations of the TP14877 tank car, from a jacketed and insulated model to a non-jacketed and non-insulated model.

Transport Canada has taken a holistic risk-based approach to enhance public safety during the transport of dangerous goods by rail. These Regulations build on previous regulatory actions: enhancements to train operations, track inspection, train speeds, sharing of information with municipalities, emergency response assistance plans and classification.

Issues

Following the Lac-Mégantic tragedy on July 6, 2013, the Transportation Safety Board launched an investigation into the causal and contributing factors of the accident. On January 23, 2014, the Transportation Safety Board released three interim recommendations. One was specific to the TC/DOT 111 tank car used to transport crude oil. It recommended that

The Department of Transport [Transport Canada] and the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration require that all Class 111 tank cars used to transport flammable liquids meet enhanced protection standards that significantly reduce the risk of product loss when these cars are involved in an accident.

The Transportation Safety Board has publicly indicated that TC/DOT 111 tank cars, in addition to the newly adopted TP14877/CPC 1232 standard in Canada, are not sufficiently crash resistant and/or robust to withstand the forces in an accident, which leads to a significant risk of tank car failure and release of dangerous goods during an incident. The Transportation Safety Board has indicated that these tank cars should be phased out as quickly as possible.

On April 23, 2014, in response to the TSB interim recommendation, the Minister of Transport announced that Transport Canada would require the phase out/retrofit of older DOT 111 tank cars used for the transport of crude oil by May 1, 2017.

As these tank cars freely travel across North American borders on a daily basis carrying various flammable liquids to downstream markets, a harmonized North American solution for new tank car standards, retrofit requirements and timelines is essential.

The exponential increase in surface movement of crude oil and ethanol over the last 10 years, as well as the increase in the transport by rail of other refined flammable liquids, has led Transport Canada to carefully consider transportation safety impacts associated with the transport by rail of flammable liquids. That analysis has determined that there is a need for Canada to update the requirements for the design, manufacture and selection of tank cars for the transportation of dangerous goods by rail.

Objectives

The Regulations Amending the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Regulations (TC 117 Tank Cars) has three objectives. Firstly, it provides for a new class of tank car, called the TC/DOT 117, for the selection and use during the transport of flammable liquids in Canada, which includes requirements for thicker steel, full head shield protection, thermal protection and a jacket, top-fitting protection, and new bottom outlet requirements. This new tank car is designed to reduce the risk of a release of a flammable liquid during an incident.

Secondly, it provides performance-based requirements for the construction of the TC/DOT 117, as well as for the retrofitting of TC/DOT 111 tank cars. In addition, it also provides prescriptive requirements to retrofit older tank cars and TP14877/CPC 1232 tank cars enabling industry to choose between either a performance or prescriptive solution to retrofitting their tank cars.

Finally, the Regulations introduce a phase-out schedule for TC/DOT 111 tank cars and TP14877/CPC 1232 tank cars announced by the Minister of Transport on April 23, 2014, in her response to the Transportation Safety Board interim recommendation of January 23, 2014. These Regulations prescribe the timing requirements associated with the above-noted retrofit requirements.

Description

The Regulations introduce a new class of tank car for flammable liquid dangerous goods service and requires rail tank cars destined for flammable liquid service (e.g. gasoline, diesel fuel, and aviation fuel) to be built to these specifications.

The specifications require thicker steel, full head shield protection, a thermally protected and jacketed car, top-fitting protection, and new bottom outlet requirements. The Regulations also require any new tank car used for flammable liquid dangerous goods service to be manufactured on or after October 1, 2015, to be built to the TC/DOT 117 standard.

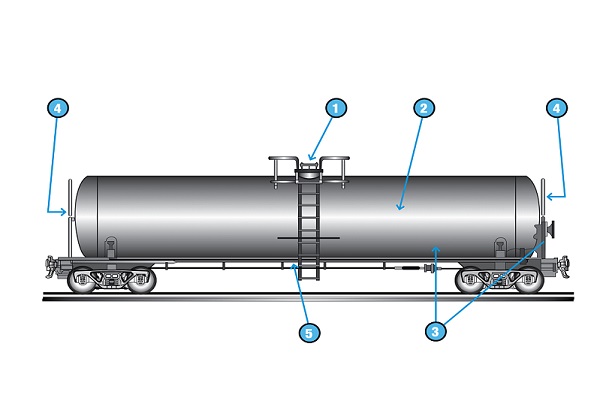

Below is a diagram, which outlines the features of the TC/DOT 117.

- 1. Top-fitting protection — This feature essentially covers the valves and accessories on top of a tank car. It also protects the pressure release valve from damage. For the TC/DOT 117 tank car, the top-fitting requirements is similar to the TP14877/CPC 1232 requirements.

- 2. Thermal protection including a jacket — This feature is an outer cover that is placed on the exterior of the shell, used mainly to provide thermal protection and keep insulation in place. The thermal protection required for the TC/DOT 117 tank car has to withstand a 100-minute pool fire and a 30-minute jet fire without rupturing.

- 3. Thicker normalized steel — Thicker shell and heads provide improved puncture resistance and structural strength. Using normalized steel improves the toughness and ductility of the material, providing increased fracture resistance of the tank car. The Regulations prescribe a thickness of 14.3 mm (9/16 inch).

- 4. Head shields — This required feature helps protect the head of the tank car from puncture. The improved TC/DOT 117 requires a full head shield that covers the entire head of the tank car.

- 5. Improved bottom outlet valves — This required feature is designed for valves to withstand derailments and helps to ensure they don’t leak during a potential accident.

Retrofit requirements for DOT 111/TP14877/CPC 1232 tank cars

There are several variations of the TC/DOT 111 and TP14877/CPC 1232 tank cars, from a jacketed and insulated model to a non-jacketed and non-insulated model. The table below outlines the different features between the three tank cars (TC/DOT 111, TP14877/CPC 1232 and TC/DOT 117).

Comparison table of features for TC/DOT 111/ TP 14877/CPC 1232 and TC/DOT 117

| Specifications | Older legacy DOT 111 tank cars | DOT-111 (TP14877/ CPC 1232) built since 2011 to standard published in Part II of the Canada Gazette July 2, 2014 | New TC/DOT 117 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Head shields | No | Half | Full |

| 2. Top-fitting protection | Optional | Mandatory | Mandatory |

| 3. Thermal protection (jacket) | Optional | Optional | Mandatory |

| 4. Thickness of steel | 11.1 mm (7/16 inch) | 12.7 mm (1/2 inch) for non-jacketed cars 11.1 mm (7/16 inch) for jacketed cars | 14.3 mm (9/16 inch) minimum |

| 5. Performance standard for bottom outlet valves | No | No | Yes |

| 6. Performance standard for thermal protection, top-fitting protection and head and shell puncture resistance | No | No | Yes |

The Regulations establish the retrofit requirements for older TC/DOT 111 tank cars and the TP14877/CPC 1232 tank car. It entrenches in regulation the Minister of Transport’s announcement of April 23, 2014, in response to the Transportation Safety Board’s interim recommendations, to phase out older TC/DOT 111 tank cars used to transport crude and ethanol.

As for retrofit requirements for TC/DOT 111 tank cars (legacy tank cars) and TP14877/CPC 1232 tank cars, the Regulations enable a person to retrofit a tank shell and head puncture resistance to a performance standards or to the prescriptive specifications that follow.

Performance-based retrofit

For tank car heads, the end structures of tank cars must be able to withstand the frontal impact of a loaded freight car, including the coupler, at a speed of 8.05 m/s or 29 km/h (18 mph). In order for a tank car to meet retrofit puncture resistance standards for tank car heads, any test performed must demonstrate that there was no leaking through the shell or head due to this impact. The test is successful if there is no visible leak from the standing tank car for at least one hour after the impact.

For tank car shells, the shell structure of tank cars must be able to withstand the side impact of a loaded freight car, including the coupler, at a speed of 5.36 m/s or 19.3 km/h (12 mph). In order for tank car side puncture resistance to meet the retrofit resistance standard, any test performed must demonstrate that there was no leaking through the shell or head due to this impact. The test is successful if there is no visible leak from the standing tank car for at least one hour after the impact.

It is also possible for tank car manufacturers and tank car owners to use computer modeling to validate their new designs or retrofit packages. The required testing validating the performance criteria may be substituted by numerical modelling and simulation if the model and simulation methods are acceptable to Transport Canada, and if the model and simulation were validated by test data.

Prescriptive specifications for tank car retrofit

Alternatively, for TP14877/CPC 1232 tank cars built since 2011, as well as older legacy TC/DOT 111 tank cars, these Regulations would enable a person to retrofit these tank cars to meet the specifications published on July 2, 2014, for the jacketed TP14877/ CPC 1232 tank cars, with additional modifications.

These modifications include new bottom outlet valves that meet the performance requirement established for bottom outlet valves for the TC/DOT 117 tank car and enhanced thermal protection requirements for pool and jet fires, as outlined in the TC/DOT 117 specifications.

In addition, the jacket for the TP14877/CPC 1232 tank car needs to meet minimum thickness requirements of three millimeters (gauge 11 steel) using the steel standard ASTM A1011 or equivalent. For legacy TC/DOT 111 tank cars, the tank car can be modified in the steel of its original construction.

Once retrofitted to the above-noted requirements, a tank car will be available for flammable liquid service for the rest of its service life.

As for top-fitting protection on older TC/DOT 111 tank cars, due to the technical complexity (all tank cars are different — e.g. valves in different positions) Transport Canada requested in November 2014 that industry form a task force under the Association of American Railroad (AAR) Tank Car Committee to bring forward an appropriate engineering solution to enable top-fitting protection on these tank cars. Transport Canada continues to participate in the task force. Both the Federal Railroad Administration and Transport Canada sit on the AAR Tank Car Committee, which will approve the Task Force recommendation. Any approved AAR Tank Car Committee proposal, as agreed by tank car members, is issued by circular and would then be binding on member companies. This voluntary industry standard would be brought forward in a future revision of the standard and become part of the Canadian regulations at a later date. Transport Canada expects that an appropriate solution will be found shortly and implemented at the time of retrofitting.

Phase-out schedule

The Regulations establish a phase-out/usage schedule for legacy TC/DOT 111 and TP14877/CPC 1232 tank cars. To determine which tank cars are removed from service, Transport Canada is following a risk-based approach. This approach removes the oldest and least crash resistant tank cars considering the volume of flammable liquid transported first. Industry has indicated to Transport Canada that 28% of the legacy tank car fleet will be retired or repurposed instead of retrofitted. The risk based approach is outlined below.

Reporting

Transport Canada is introducing an optional requirement for tracking of the tank car retrofit progress by the industry. Should this option be triggered, starting January 1, 2017, consignors would have to provide to the Minister, upon reasonable notice given by the Minister, the number of tank cars that they own or lease that have been retrofitted, and the number that has not yet been retrofitted.

However, Transport Canada has worked with the industry through the Association of American Railroads Tank Car Committee to develop a voluntary approach to track and report on the number of tank cars that have been retrofitted. Should this voluntary approach not be successful in providing the proper information to Transport Canada, the Regulations provide for the capability to compel the production of such information.

Clarifying amendment

Finally, an additional amendment to the TDGR is being made to clarify the intent of amendments previously published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, on December 31, 2014, entitled Regulations Amending the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Regulations (Lithium Metal Batteries, ERAPs and Updates to Schedules). Contained within these amendments were new requirements for shippers of petroleum crude oil and ethanol by rail to have an approved emergency response assistance plan for quantities of 10 000 litres or more. This amendment modifies subsection 7.1(6) as well as the ERAP index under column 7 of Schedule 1 and also introduces a new special provision 150 to clarify that the ERAP requirement only applies to the transport of these dangerous goods by rail, not by other modes of transport.

| Last Day to Use Tank Cars in Column 3 for Dangerous Goods in Column 2 | Flammable Liquid / Packing Group(s) [PG] | Tank Car Type Removed from Service | North American Fleet to be Retrofitted | Canadian Tank Car Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| April 30, 2017 | Crude oil (PG I, II, III) | DOT 111 Non-jacketed | After 28% Retirement rate 16 625 | 4 988 |

| February 28, 2018 | Crude oil (PG I, II, III) | DOT 111 Jacketed | After 28% Retirement rate 5 027 | 2 759 |

| March 31, 2020 | Crude oil (PG I, II, III) | CPC 1232 Non-jacketed | After 28% Retirement rate 21 993 | 6 849 |

| April 30, 2023 | Ethanol (PG II) | DOT 111 Non-jacketed | After 28% Retirement rate 19 467 | 974 |

| April 30, 2023 | Ethanol (PG II) | DOT 111 Jacketed | 88 | 0 |

| June 30, 2023 | Ethanol (PG II) | CPC 1232 Non-jacketed | 751 | 0 |

| April 30, 2025 | Crude oil and ethanol and all remaining flammable liquids (PG I, II, III) | CPC 1232 Jacketed in crude oil service and | 35 631 in crude oil service | 10 698 CPC 1232 Jacketed |

| all remaining DOT 111 jacketed and CPC 1232 jacketed and non-jacketed tank cars | After 28% retirement rate for older TC/DOT 111 tank cars 28 600 |

8 580 in flammable liquid service other than crude and ethanol |

Following the retrofit requirements in the Regulations, a person is required to transport a flammable liquid in either the new TC/DOT 117 tank car, a retrofitted TC/DOT 111, a TP14877/ CPC 1232 tank car or a retrofitted TP14877/CPC 1232 tank car corresponding to the above-noted timelines. The Regulations prescribe the tank car required to be used tied directly to the timelines above.

Regulatory and non-regulatory options considered

Tank cars are built to the specifications dictated under the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Regulations (TDGR) and associated standards. A person in Canada who offers for transport a dangerous good is required to classify the dangerous good properly and place the dangerous good in the approved means of containment built to the appropriate standard.

A voluntary approach to adopting a new tank car standard was not considered to be a feasible option given the risks involved in transporting flammable liquids and given the integrated nature of the North American rail industry which relies on a fairly harmonized set of regulations and standards both in the United States and in Canada.

Therefore, it is important that Transport Canada bring forward appropriate tank car specifications, as well as retrofit requirements, to protect public safety. In light of this, non-regulatory options were not considered to be feasible or likely to be effective in achieving the desired safety objectives of this proposal.

As part of its regulatory analysis, Transport Canada also considered a longer implementation schedule to allow stakeholders more time to retrofit or build new tank cars. However, based on our analysis of industry’s build and retrofit capacity, it was determined that the present implementation schedule strikes the correct balance between the need to quickly ensure greater safety in the transport of flammable liquids by rail and the need to provide adequate time to comply with the new requirements and to ensure there are no potential supply interruptions due to a shortage of compliant tank cars to the new specifications.

Benefits and costs

A cost-benefit analysis has been conducted to assess the impact of the Regulations on stakeholders. The cost-benefit analysis identifies, quantifies and monetizes, where possible, the incremental costs and benefits of the tank car Regulations used in the transport of crude oil, ethanol and other flammable liquids in Canada.

Time frame: A 20-year (2015–2034) time period was used to evaluate the economic impact of these Regulations. A 7% discount rate has been used for the purposes of this analysis.

Baseline scenario: It is assumed that industry would continue to order or build jacketed TP14877/CPC 1232 tank cars to transport crude oil and ethanol in the absence of any new regulations. Industry has indicated to Transport Canada that this is the current practice since the Lac-Mégantic incident. The baseline scenario also assumes that legacy TC/DOT 111 or TP14877/CPC 1232 tank cars that are in flammable liquid dangerous good service would not be retrofitted without these new Regulations.

With harmonized Canada/U.S. TC/DOT 117 final Regulations, this analysis considers the cost associated with legacy TC/DOT 111 and TP14877/CPC 1232 tank cars that are owned or leased by Canadian companies, as well as tank cars operating across the Canada/U.S. border. Finally, the analysis includes the 40-year life expectancy of a legacy TC/DOT 111 tank car and the TP14877/CPC 1232 tank car.

For the purpose of this analysis, flammable liquids have been subdivided into three flammable liquid groups: crude oil, ethanol and other flammable liquids. The analysis takes into consideration the prescribed retrofit requirements in the Regulations and the phase-out/retrofit timeline schedule. In the United States, although the final rules have been harmonized as best as practical, U.S. unjacketed tank cars will have a longer scheduled timeline reflecting the larger quantity of unjacketed tank cars requiring retrofitting in the U.S. fleet. Until these tank cars are retrofitted, they will not be able to be used in Canada for crude oil service after May 1, 2017.

Based on industry information, it is estimated that 41 113 tank cars are either owned or leased in Canada. Of the above-noted total, 28 307 tank cars are used in crude oil service, 1 353 tank cars in ethanol service, and 11 453 tank cars used for all other flammable liquid service. A breakdown of the Canadian fleet by type of tank cars and commodity is presented below in table 1.

Table 1: Number of Tank Cars by Tank Car Type and Commodity |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Crude oil | Ethanol | Other flammable liquids | |

| TC/DOT 111 legacy non-jacketed | 6 928 | 1 353 | 9 749 |

| TC/DOT 111 legacy jacketed | 3 832 | - | 513 |

| TP14877/CPC 1232 non-jacketed | 6 849 | - | 1 133 |

| TP14877/CPC 1232 jacketed | 10 698 | - | 60 |

| Total | 28 307 | 1 353 | 11 453 |

Key assumptions

- It is estimated that the crude oil tank car fleet will grow by 8% in 2015 and 8% in 2016. This growth reflects the current industry investment commitments in tank car orders as well as planned announced spending for additional rail loading and off-loading capabilities and new well capacity coming online. At present, beginning in 2017, the demand for new crude oil tank cars is projected to flatten. This is attributed to the current world crude oil market price. It also takes into account future proposed pipeline capacity expected to come online. Should crude oil prices recover to more normal levels, Transport Canada expects that demand for tank cars would increase to meet transport requirements. However, for the purpose of this analysis, growth in the transport of crude oil by tank cars is tied to the current price of crude oil and industry statements that transport of crude by rail will continue to be important in delivering crude oil to markets. Based on these assumptions, it is estimated that an additional 4 711 crude oil tank cars will be required in Canada during the time frame used for this analysis.

- The ethanol fleet is assumed to maintain its current fleet size over the 20 years of this analysis.

- As for other tank cars in flammable liquid service other than crude or ethanol, industry has indicated that it expects a slight annual increase over the next four or five years and then a stabilized fleet size over the remaining period. However, due to lack of data, the present analysis adopts the assumption of no growth for the number of tank cars in other flammable liquid services during the entire 20 years.

- As per table 1, there are 22 373 legacy TC/DOT 111 tank cars in the Canadian fleet. Industry has indicated that 28% of the legacy fleet will be retired or repurposed. Therefore, Transport Canada expects 6 265 of the 22 373 legacy tank cars will be retired or repurposed, either because of the age of the tank cars or age and tank car design in relation to retrofit requirements making retrofitting a non-viable economic choice. These assumptions are reflected in Transport Canada’s analysis. Of the 6 265 TC/DOT 111 legacy tank cars that will be retired or repurposed, Transport Canada estimates that 5% of the total number of tank cars being retired is attributed to the end of their 40-year lifecycle. Finally, it is estimated that, of the total TC/DOT 111 legacy Canadian fleet, 28.6% of these tank cars in crude oil service, 11.6% in ethanol service, and 6.9% in other flammable liquid service, are owned by Canadian companies. The remainder of the Canadian tank car fleet would be leased.

Costs

For the purpose of this analysis, the following costs have been included: costs associated with the purchase of new TC/DOT 117 tank cars compared to the current cost to purchase a jacketed TP14877/CPC 1232 tank car, costs associated with the retrofit requirements for both legacy TC/DOT 111 and TP14877/CPC 1232 tank cars and their associated out-of-service costs to meet retrofit requirements.

- Costs associated with new TC/DOT 117 tank cars (construction costs and higher leasing rates)

Considering the above, it is estimated that 6 265 new TC/DOT 117 tank cars would be ordered (either purchased or leased) to replace the retired/repurposed Canadian TC/DOT 111 legacy fleet. It is also estimated that an additional 4 711 new TC/DOT 117 tank cars will be ordered to meet transport of crude oil by rail demand.

The cost-benefit analysis includes the incremental cost differential between the new TC/DOT 117 tank car and the jacketed TP14877/CPC 1232 tank car for the 5% (313) of the 6 265 tank cars that would be retired because of age following the Regulations, as those tank cars would have been built to the TP14877/CPC 1232 standard. As for the remaining 95% (5 952) of the 6 265 tank cars being retired or repurposed, the cost of the new TC/DOT 117 is being used. Transport Canada is aware that industry may repurpose some of these tank cars other than in flammable liquid service. Since industry data is not available at this time, it has not been considered as part of this analysis. As for the 4 711 new tank cars forecasted to be ordered for flammable liquid service to meet crude oil transport demand, the cost differential between a new TC/DOT 117 and a jacketed TP14877/CPC 1232 tank car was used. The cost differential between a TC/DOT 117 and a jacketed TP14877/CPC 1232 tank car is forecasted at $7,471 (US$6,000) and the annual increase of leasing cost at $1,494 (US$1,200). (see footnote 2)

For the remaining 4 711 new tank car orders, the cost-benefit analysis includes the estimated new construction costs associated with Canadian purchased TC/DOT 117 tank cars, and its higher leasing costs as compared to that of TC/DOT 111 legacy cars (both jacketed and non-jacketed).

The construction cost of a TC/DOT 117 is estimated at $199,216 (US$160,000), and the leasing cost differential between a TC/DOT 117 and a TC/DOT 111 legacy car is $8,218 (US$6,600) [non-jacketed] and $4,781 (US$3,840) [jacketed].

The present value (includes construction costs and higher leasing costs) associated with the new TC/DOT 117 tank cars over a 20-year period is estimated at $449,010,176, corresponding to an annualized value of $42,383,384.

- Costs associated with retrofitted tank cars (retrofitting costs and higher leasing rates)

Following the above analysis, Transport Canada estimates that a total of 34 848 Canadian TC/DOT 111 legacy tank cars and TP14877/CPC 1232 tank cars will be retrofitted. It is estimated that 16 108 of these tank cars are TC/DOT 111 legacy cars (12 980 non-jacketed and 3 128 jacketed), and 18 740 are TP14877/CPC 1232 tank cars (7 982 non-jacketed and 10 758 jacketed). Retrofit costs are associated with the prescribed timeline schedule in the Regulations and the number of tank cars estimated to be retrofitted per year. North American retrofit capacity is estimated at a starting rate of 7 500 tank cars per year following a six-month ramp up period. Table 2 presents the tank cars retrofitted annually between May 1, 2015, and April 30, 2025. It is also assumed that industry will retrofit, as per its comments to Transport Canada, jacketed TP14877/CPC 1232 tank cars at the time of requalification testing.

Table 2: Number of Canadian Tank Cars Retrofitted Annually by Type of Tank Cars, 2015–2025 |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |

| TC/DOT 111 legacy non-jacketed | 1 662 | 2 494 | 832 | 0 | 0 | 237 | 316 | 316 | 2 444 | 3 509 | 1 170 |

| TC/DOT 111 legacy jacketed | 0 | 0 | 2 207 | 552 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 123 | 185 | 61 |

| TP14877/CPC 1232 non-jacketed | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 740 | 3 288 | 821 | 0 | 0 | 378 | 567 | 188 |

| TP14877/CPC 1232 jacketed | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 535 | 1 070 | 3 229 | 4 309 | 1 615 |

The retrofitting cost associated with a tank car is dependent on the type and specifications of the tank car. Transport Canada estimates that the per-unit retrofitting costs for a legacy TC/DOT 111 non-jacketed tank car, TC/DOT 111 legacy jacketed tank car, TP14877/CPC 1232 non-jacketed tank car, and TP14877/CPC 1232 jacketed tank car is $52,419 (US$42,100), $37,478 (US$30,100), $37,478 (US$30,100) and $3,362 (US$2,700), respectively.

These above costs are attributed to the owner of the tank car. For an organization that leases a tank car, the costs associated with the retrofit are expected to be passed on to the lessor through a higher lease rate. The additional annual leasing cost associated with the prescribed retrofit requirements are $3,935 (US$3,160) [non-jacketed TC/DOT 111], $2,838 (US$2,279) [jacketed TC/DOT 111], $1,894 (US$1,521) [non-jacketed TP14877/CPC 1232] and $157 (US$126) [jacketed TP14877/CPC 1232].

The present value (retrofitting costs and higher leasing costs) over the 20-year period is estimated at $543,632,308, amounting to an annualized value of $51,315,044.

- Out-of-service costs

Out-of-service costs have also been considered as part of the cost-benefit analysis. It is forecasted that an entity who leases a tank car in Canada would have access to a required tank car without any service interruption. This analysis is based on the fact that the Canadian fleet of tank cars is a small subset of the overall North American tank car fleet. In addition, with the harmonization of tank car retrofit timelines, the total North American fleet is being retrofitted to similar timelines, and, therefore a tank car would be expected to be available to Canadian lessors.

Based on industry information, Transport Canada estimates that it would take 12 weeks to retrofit a TC/DOT 111 legacy non-jacketed tank car and 8 weeks for a TC/DOT 111 legacy jacketed tank car or a TP14877/CPC 1232 non-jacketed tank car. No out-of-service costs have been attributed to the jacketed TP14877/CPC 1232 tank cars, as industry has indicated during consultations that it would retrofit these tank cars at the time of their requalification, which will occur within the retrofit schedule.

Following the above approach, multiplying the length of time absent from service by the rate based on annual leasing costs, Transport Canada can calculate the value of the service interruption for different types of tank cars. Therefore, the total out-of-service costs present value is estimated at $12,516,967, corresponding to an annualized value of $1,181,513.

Therefore, the total costs of the Regulations over a 20-year period (2015–2034) are estimated at a present value of $1,005 million, annualized at $90 million yearly.

Benefits

While transporting flammable liquids in a TC/DOT 117 tank car or a retrofitted tank car would not completely eliminate the probability of a release of a flammable liquid during a rail incident, the enhanced tank cars would significantly reduce the risk of release and the associated consequences.

A dangerous goods incident involving a release of flammable liquids, or even an explosion caused by the flammable liquids, can cause numerous significant impacts on public safety, which includes the environment. In addition to injuries and fatalities, an incident can cause property damages, evacuation costs, environmental clean-up costs, lost of productivity, business closures, etc. The magnitude of these costs is influenced by the quantity of the release, the type of flammable liquid released and the incident location.

Due to data limitations and forecasting limitations, it is difficult to predict or estimate the exact number and magnitude of future incidents, or specify exactly how many incidents would be prevented because of these Regulations. Therefore, the benefits resulting from the enhanced tank car standards are discussed using an inverse cost-benefit analysis method. Specifically, the potential costs of certain incidents are examined, and then, the number of incidents that would need to be prevented by the Regulations for the costs (of implementing the Regulations) and the benefits (incidents to be prevented) to be equal is calculated.

Based on the information of recent derailments of tank cars carrying flammable liquids, and taking into consideration the increase demand for rail transportation of flammable liquids, such as crude oil and the make up of the current fleet, it is estimated that the average expected release in the event of an incident is approximately 200 627 litres (53 000 U.S. gallons). (see footnote 3) The U.S. Department of Transportation has used an estimated cost of $66 per litre ($249 [US$200] per U.S. gallon) released for a typical incident. Presuming the same value, it implies that the average cost of a typical derailment of tank cars carrying flammable liquids is about $13,197,000. In the case of a catastrophic situation, such as the Lac-Mégantic tragedy, the estimated value of all the damages currently sits at $1.5 billion (US$1.2 billion).

If Transport Canada establishes the present value of the benefits equal to the total costs ($1,005 million) and divides it by the average cost of a typical derailment ($13,197,000), one obtains an estimated total of 76 typical incidents or 3.8 incidents per year. This corresponds to the minimum number of typical incidents that need to be prevented or that would be mitigated (by the use of a more robust tank car) for the costs of the Regulations to equal its benefits (without any other prevention).

Alternatively, in the case of a high-consequence incident, like the Lac-Mégantic incident, only one derailment needs to be prevented for the benefits to be greater than the costs. Because of the increasing demand for rail transportation in flammable liquids, especially for crude oil, it is expected that the benefits of the Regulations from preventing or mitigating the consequences of derailments, spills or fires will likely exceed the estimated costs.

Summary

The estimated costs and benefits of the Regulations on enhancing the standards for tank cars in flammable liquid services are summarized in Table 3. The estimates are dependent on the value of key parameters, such as the growth rate of the fleet, the estimated retrofitting costs and the leasing costs.

Table 3 — Cost-benefit statement

| 2015 Base Year |

2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2020 | 2022 | 2025 | 2034 Final Year |

Total (PV) |

Annualized Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Quantified impacts (in CAN$, 2015 price level/constant dollars) | ||||||||||

| Costs associated with new TC 117 | $42,241,916 | $68,156,027 | $80,851,446 | $31,019,687 | $21,747,004 | $24,232,877 | $48,716,274 | $42,754,991 | $449,010,176 | $42,383,384 |

| Costs associated with retrofitted tank cars | $26,650,239 | $45,841,210 | $51,524,317 | $52,087,449 | $39,339,579 | $34,476,958 | $67,951,563 | $62,142,337 | $543,632,308 | $51,315,044 |

| Out-of-service costs | $1,801,473 | $2,704,106 | $2,831,423 | $2,915,549 | $831,555 | $140,325 | $359,762 | $0 | $12,516,967 | $1,181,513 |

| Total costs | $70,693,628 | $116,701,343 | $135,207,187 | $86,022,684 | $61,918,138 | $58,850,161 | $117,027,599 | $104,897,328 | $1,005,159,451 | $94,879,941 |

| Total benefits | n/a | |||||||||

| B. Qualitative impacts | ||||||||||

| Costs | There could be additional costs on fuel consumption and maintenance due to the increased weight of the enhanced tank cars. However, it is extremely difficult to estimate the associated costs due to data limitations. In certain cases where flammable liquids (for example ethanol) are imported to Canada from the U.S., while the U.S. companies have to comply with the enhanced tank cars standards by paying higher costs (new construction, retrofitting and higher leasing rates), the U.S. companies might decide to transfer the increased costs to Canadian entities by increasing the import price of the products (ethanol).Therefore, there might be an additional financial burden on Canadian companies. Due to lack of data, this type of costs is not estimated in the present analysis. |

|||||||||

| Benefits | The enhanced tank cars are deemed to be able to reduce the risks of release and the seriousness of the consequences. In terms of effective prevention of incidents, numerous costs can be saved, including healthcare costs, property damages, evacuation costs, environmental clean-up costs, lost of productivity, and lost of human life. As discussed above, if the Regulations can prevent at least 76 typical incidents or one catastrophic incident over 20 years, the benefits are expected to exceed the costs of the Regulations. | |||||||||

Note: Numbers may not add up due to rounding.

“One-for-One” Rule

The “One-for-One” Rule does not apply for these Regulations, as they do not introduce any new administrative burden on industry.

With respect to the optional reporting requirement, Transport Canada maintains that it is not likely that there will be any administrative burden associated with this reporting requirement, as Transport Canada is confident that the voluntary approach will be implemented successfully in collaboration with the Association of American Railroads Tank Car Committee.

Small business lens

The small business lens does not apply to these Regulations, as they do not impose any administrative burden on small business. These Regulations bring forward a new tank car standard used for transport of flammable liquid by rail, as well as new retrofit requirements for older TC/DOT 111 tank cars. Tank cars owners are typically large corporations or multinational leasing corporations.

Consultation

Various safety standards referenced under the TDGR are developed within technical committees composed of members of the container manufacturing industry, user industry and regulatory bodies. Standards represent the consensus view of stakeholders in their development.

The TC/DOT 117 requirements, which were posted on the Transport Canada Web site (then called TC 140) from July 18, 2014, to August 31, 2014, generated comments from provincial authorities, municipal authorities through the Federation of Canadian Municipalities, industry, carriers, first responders, and enforcement personnel.

Stakeholders welcomed the introduction of the proposed new class of tank car (TC 140) as it brings, along with the U.S. proposal, clarity and certainty back to the transport of crude oil by rail market, once a final rule is adopted and published in both countries. The main comments received during the consultations were focused in seven areas: harmonization, timelines, bottom outlet valves, pressure relief valves, electronically controlled pneumatic (ECP) brakes, repair capacity and steel thickness.

A total of 41 comments were received, where 12 were seeking clarification and/or were neutral. Comments were received from provincial/municipal authorities, tank car builders and railway suppliers, carriers, oil and gas industry and industry associations involved in the transport of flammable liquid dangerous goods.

Fifteen of the comments received were supportive of Transport Canada’s push for harmonization with the U.S. and highlighted the importance of harmonization between regulatory requirements in Canada and the U.S., as tank cars travel across Canadian/U.S. borders on a daily basis. Stakeholders are concerned that should regulatory requirements not be similar, the efficient trade of flammable liquids would be at risk of potentially causing shortages of gasoline, diesel fuel and aviation fuel in both countries.

On timelines and repair capacity, three comments were supportive of the timelines established to phase out older TC/DOT 111 tank cars. Twenty comments indicated that the three-year phase out of TC/DOT 111 tank cars for the transport of crude and ethanol by May 1, 2017, is an aggressive target. Some comments expressed concern about the possible lack of sufficient repair and/or retrofit capacity in light of the number of tank cars requiring retrofits in light of what they considered an aggressive timeline for implementation of the new standard. Other stakeholders indicated that repair facilities will also be required to retest other means of containment, including legacy cars, in the coming years to stay in compliance with regulatory requirements. These compliance and verification tests, they maintain, will take away capacity to retrofit legacy tank cars.

Seven comments were received on the bottom outlet valve. Five comments were supportive, two suggested that the Regulations be modified to enable easier compliance with the same safety result. All stakeholders were supportive of upgrading the bottom outlet valve on tank cars used for flammable liquids. Transport Canada has adjusted the bottom outlet valve requirement to reflect comments received.

Five comments were received on the pressure relief valve. All were supportive of these new requirements on flammable liquid tank cars.

On ECP braking, 10 comments were received. Two were supportive of new braking requirements for flammable liquid tank cars noting the quicker emergency braking performance associated with ECP brakes. Eight comments were concerned about the applicability of ECP trains in a multi-tank car train and believe the braking improvements would apply mostly to unit trains of flammable liquids. Transport Canada still believes that ECP braking provides a significant safety advantage (quicker stopping, even distribution of energy forces during emergency breaking). Following consultations, ECP brakes have been removed from the standard. The intention will now be to place braking requirements, including ECP brakes, into an operational requirement. To this end, technical discussions with the U.S. to achieve a harmonized Canada/U.S. braking requirements are being undertaken. Canadian industry will continue to be consulted as Transport Canada implements the appropriate braking requirements through its Rail Safety Division.