Vol. 148, No. 21 — October 8, 2014

Registration

SOR/2014-207 September 19, 2014

CANADIAN ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION ACT, 1999

Regulations Amending the Passenger Automobile and Light Truck Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations

P.C. 2014-935 September 18, 2014

Whereas, pursuant to subsection 332(1) (see footnote a) of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (see footnote b), the Minister of the Environment published in the Canada Gazette, Part I, on December 8, 2012, a copy of the proposed Regulations Amending the Passenger Automobile and Light Truck Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations, substantially in the annexed form, and persons were given an opportunity to file comments with respect to the proposed Regulations or to file a notice of objection requesting that a board of review be established and stating the reasons for the objection;

Therefore, His Excellency the Governor General in Council, on the recommendation of the Minister of the Environment, pursuant to sections 160 and 162 of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (see footnote c), makes the annexed Regulations Amending the Passenger Automobile and Light Truck Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations.

REGULATIONS AMENDING THE PASSENGER AUTOMOBILE AND LIGHT TRUCK GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSION REGULATIONS

AMENDMENTS

1. (1)The definitions “car line” and “transmission class” in subsection 1(1) of the Passenger Automobile and Light Truck Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations (see footnote 1) are repealed.

(2) The definition “curb weight” in subsection 1(1) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

“curb weight”

« masse en état de marche »

“curb weight” means, at the manufacturer’s choice, the actual or manufacturer’s estimated weight of a vehicle in operational status with all standard equipment and weight of fuel at nominal tank capacity and the weight of optional equipment.

(3) Subsection 1(1) of the Regulations is amended by adding the following in alphabetical order:

“cargo box length at the floor”

« longueur de caisse au plancher »

“cargo box length at the floor” means the longitudinal distance between the inside front of the cargo box and the inside of the closed endgate as measured at the surface of the cargo box floor along the vehicle’s centreline.

“cargo box length at the top of the body”

« longueur de caisse au sommet de la carrosserie »

“cargo box length at the top of the body” means the longitudinal distance between the inside front of the cargo box and the inside of the closed endgate as measured at the height of the top of the cargo box along the vehicle’s centreline.

“cargo box width”

« largeur de la caisse de chargement »

“cargo box width” means the width of the cargo box as measured at the cargo box’s narrowest point between the wheelhouses.

“fire fighting vehicle”

« véhicule d’incendie »

“fire fighting vehicle” means a passenger automobile or light truck that is designed to be used under emergency conditions to transport personnel and equipment and to support the suppression of fires and the mitigation of other emergency situations.

“full-size pick-up truck”

« grosse camionnette »

“full-size pick-up truck” means a light truck that has a passenger compartment and a cargo box without a permanently fixed roof and that meets the following specifications:

- (a) a cargo box width of 121.9 cm (48 inches) or more;

- (b) a cargo box length of 152.4 cm (60 inches) or more, which length corresponds to the lesser of the cargo box length at the top of the body and the cargo box length at the floor; and

- (c) a towing capability of 2 267 kg (5,000 pounds) or more or a payload capability of 771 kg (1,700 pounds) or more.

“GCWR”

« PNBC »

“GCWR” means the gross combination weight rating specified by a manufacturer as the maximum combined weight of a towing vehicle, its passengers and its cargo, plus the weight of the trailer and its cargo.

“mild hybrid electric technology”

« technologie électrique hybride légère »

“mild hybrid electric technology” means a technology that includes automatic start/stop capability and regenerative braking capability, and with which the recovered energy is at least 15% but less than 65% of the total braking energy, as determined in accordance with the test procedure set out in section 116(c) of Title 40, chapter I, part 600, subpart B, of the CFR.

“natural gas vehicle”

« véhicule au gaz naturel »

“natural gas vehicle” means a vehicle designed to operate exclusively on natural gas.

“payload capability”

« charge utile »

“payload capability” means the difference between the GVWR and curb weight of a vehicle.

“strong hybrid electric technology”

« technologie électrique hybride complète »

“strong hybrid electric technology” means a technology that includes automatic start/stop capability and regenerative braking capability, and with which the recovered energy is at least 65% of the total braking energy, as determined in accordance with the test procedure set out in section 116(c) of Title 40, chapter I, part 600, subpart B, of the CFR.

“towing capability”

« capacité de remorquage »

“towing capability” means the difference between the GCWR and GVWR of a vehicle.

(4) Subsection 1(2) of the Regulations is repealed.

2. Subsection 6(2) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Exception

(2) Subsection (1) does not apply to any company that, since September 23, 2010 or an earlier date, has been authorized to apply the national emissions mark to a vehicle under the On-Road Vehicle and Engine Emission Regulations.

3. Subsections 8(3) and (4) of the Regulations are replaced by the following:

Fleets of the 2011 model year

(3) A company’s fleet of passenger automobiles or light trucks of the 2011 model year does not include vehicles that were manufactured before September 23, 2010, unless the company elects to include all of its passenger automobiles or light trucks of the 2011 model year in the fleet in question and reports that election in its end of model year report.

Emergency vehicles

(4) Despite subsection (1), a company may, for the purposes of sections 10, 13 to 31 and 33 to 40, elect to exclude emergency vehicles from its fleets and its temporary optional fleets of passenger automobiles and light trucks of the model year corresponding to the year during which this subsection comes into force and any subsequent model year, if it reports that election in its end of model year report for that model year.

4. Section 9 of the Regulations is amended by adding the following after subsection (3):

Exception — ambulance or fire fighting vehicle

(4) Despite subsection (2), an ambulance or a fire fighting vehicle may be equipped with a defeat device if the device is one that is automatically activated during emergency response operations to maintain speed, torque or power in either of the following circumstances:

- (a) the emission control system is in an abnormal state; or

- (b) the device acts to maintain the emission control system in a normal state.

5. Subsection 10(1) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Nitrous oxide and methane emission standards

10. (1) Subject to subsection (2) and section 12, passenger automobiles and light trucks of the 2012 model year or a subsequent model year must conform to the following exhaust emission standards for nitrous oxide (N2O) and methane (CH4) for the applicable model year:

- (a) the standards for nitrous oxide (N2O) and methane (CH4) set out in section 1818(f)(1) of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter C, part 86, subpart S, of the CFR;

- (b) the standards for nitrous oxide (N2O) set out in section 1818(f)(1) of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter C, part 86, subpart S, of the CFR and the alternative standards for methane (CH4) determined in accordance with section 1818(f)(3) of that subpart;

- (c) the alternative standards for nitrous oxide (N2O) determined in accordance with section 1818(f)(3) of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter C, part 86, subpart S, of the CFR and the standards for methane (CH4) set out in section 1818(f)(1) of that subpart; or

- (d) the alternative standards for nitrous oxide (N2O) and methane (CH4) determined in accordance with section 1818(f)(3) of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter C, part 86, subpart S, of the CFR.

6. Section 11 of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Interpretation of standards

11. The standards referred to in section 10 are the certification and in-use standards for the applicable useful life, taking into account the test procedures, fuels and calculation methods set out for those standards in subpart B of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter C, part 86 of the CFR and in subpart B of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter Q, part 600, of the CFR.

7. (1) Subsection 14(1) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Non-application of the standards respecting CO2 equivalent emissions

14. (1) A company that manufactured or imported at least one passenger automobile or light truck but in total not more than 749 passenger automobiles and light trucks of either the 2008 or 2009 model years for sale in Canada is not subject to sections 13 and 17 to 20 for vehicles of the 2012 model year or a subsequent model year if

- (a) the average number of passenger automobiles and light trucks that were manufactured or imported by the company for sale in Canada is less than 750 for the three consecutive model years preceding the model year that is one year before the model year in question; and

- (b) the company submits a declaration as set out in section 35.

New companies — 2017 model year and subsequent model years

(1.1) A company that did not manufacture or import any passenger automobiles or light trucks of the 2011 to 2016 model years for sale in Canada during the 2010 to 2016 calendar years is not subject to sections 13 and 17 to 20 for vehicles of the 2017 model year or a subsequent model year if the company submits a declaration as set out in section 35 and

- (a) in the case of the first model year for which the company manufactures or imports passenger automobiles or light trucks for sale in Canada, the company manufactures or imports in total less than 750 passenger automobiles and light trucks;

- (b) in the case of the second model year for which the company manufactures or imports passenger automobiles or light trucks for sale in Canada, the company manufactures or imports in total less than 750 passenger automobiles and light trucks;

- (c) in the case of the third model year for which the company manufactures or imports passenger automobiles or light trucks for sale in Canada, the company manufactures or imports in total less than 750 passenger automobiles and light trucks; and

- (d) in the case of any subsequent model year, the average number of passenger automobiles and light trucks that are or were manufactured or imported by the company for sale in Canada for that model year and for the two preceding model years is less than 750.

(2) The portion of subsection 14(2) of the Regulations before paragraph (a) is replaced by the following:

Conditions

(2) If, for the three consecutive model years preceding the model year in question, the average number of passenger automobiles and light trucks that were manufactured or imported by a company for sale in Canada is equal to or greater than 750 — other than by reason of the company purchasing another company — the company becomes subject to sections 13, 17 to 20 and 33 for its passenger automobiles and light trucks of the following model year:

8. Section 15 of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Rounding — general

15. (1) If any of the calculations in these Regulations, except for those in paragraphs 17(4)(b) and (5)(b), subsections 17(6) and (7), section 18, subsections 18.1(1), (2), (5) and (10), sections 18.2 and 18.3 and subsection 18.4(1), results in a number that is not a whole number, the number must be rounded to the nearest whole number in accordance with section 6 of the ASTM International method ASTM E 29-93a, entitled Standard Practice for Using Significant Digits in Test Data to Determine Conformance with Specifications.

Rounding — nearest tenth of a unit

(2) If any of the calculations in paragraphs 17(4)(b) and (5)(b), subsections 17(6) and (7), section 18, subsections 18.1(1), (2), (5) and (10), sections 18.2 and 18.3 or subsection 18.4(1) results in a number that is not a whole number, the number must be rounded to the nearest tenth of a unit.

9. (1)Subsections 17(2) and (3) of the Regulations are replaced by the following:

Calculation of fleet average CO2 equivalent emission standard for 2012 and subsequent model years

(3) Subject to sections 24 and 28.1, a company must calculate the fleet average CO2 equivalent emission standard for its fleet of passenger automobiles and its fleet of light trucks of the 2012 model year and subsequent model years in accordance with the following formula:

![]()

where

- A is the CO2 emission target value for each group of passenger automobiles or light trucks, determined in accordance with subsection (4), (5), (6) or (7), as the case may be, and expressed in grams of CO2 per mile;

- B is the number of passenger automobiles or light trucks in the group in question; and

- C is the total number of passenger automobiles or light trucks in the fleet.

(2) The portion of subsection 17(4) of the Regulations before paragraph (a) is replaced by the following:

Targets — passenger automobiles of the 2012 to 2016 model years

(4) For fleets of the 2012 to 2016 models years, the CO2 emission target value applicable to a group of passenger automobiles of a given model year corresponds to the following:

(3) The portion of item 5 of the table to paragraph 17(4)(a) of the Regulations in column 1 is replaced by the following:

| Item | Column 1 Model Year |

|---|---|

| 5. | 2016 |

(4) The portion of item 5 of the table to paragraph 17(4)(b) of the Regulations in column 1 is replaced by the following:

| Item | Column 1 Model Year |

|---|---|

| 5. | 2016 |

(5) The portion of item 5 of the table to paragraph 17(4)(c) of the Regulations in column 1 is replaced by the following:

| Item | Column 1 Model Year |

|---|---|

| 5. | 2016 |

(6) The portion of subsection 17(5) of the Regulations before paragraph (a) is replaced by the following:

Targets — light trucks of the 2012 to 2016 model years

(5) For fleets of the 2012 to 2016 model years, the CO2 emission target value applicable to a group of light trucks of a given model year corresponds to the following:

(7) The portion of item 5 of the table to paragraph 17(5)(a) of the Regulations in column 1 is replaced by the following:

| Item | Column 1 Model Year |

|---|---|

| 5. | 2016 |

(8) The portion of item 5 of the table to paragraph 17(5)(b) of the Regulations in column 1 is replaced by the following:

| Item | Column 1 Model Year |

|---|---|

| 5. | 2016 |

(9) The portion of item 5 of the table to paragraph 17(5)(c) of the Regulations in column 1 is replaced by the following:

| Item | Column 1 Model Year |

|---|---|

| 5. | 2016 |

(10) Section 17 of the Regulations is amended by adding the following after subsection (5):

Targets — passenger automobiles of the 2017 model year and subsequent model years

(6) The CO2 emission target value applicable to a given group of passenger automobiles of the 2017 model year and subsequent model years corresponds to the value determined for that group in accordance with section 1818(c)(2)(i) of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter C, part 86, subpart S, of the CFR.

Targets — light trucks of the 2017 model year and subsequent model years

(7) The CO2 emission target value applicable to a given group of light trucks of the 2017 model year and subsequent model years corresponds to the value determined for that group in accordance with section 1818(c)(3)(i) of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter C, part 86, subpart S, of the CFR.

10. Section 18 of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Fleet average CO2 equivalent emission value

18. A company must calculate the fleet average CO2 equivalent emission value for its fleet of passenger automobiles and its fleet of light trucks of the 2011 model year and subsequent model years in accordance with the following formula:

D – E – F – G – H

where

- D is the fleet average carbon-related exhaust emission value for each fleet, calculated in accordance with subsections 18.1(1) and (2), taking into account subsections 18.1(6) and (7);

- E is the allowance for the reduction of air conditioning refrigerant leakage, calculated in accordance with subsection 18.2(1);

- F is the allowance for the improvement of air conditioning system efficiency, calculated in accordance with subsection 18.2(2);

- G is the allowance for the use of innovative technologies that result in a measurable CO2 emission reduction, which corresponds to the sum of the allowances calculated in accordance with subsections 18.3(1) or (3), and (5); and

- H is the CO2 allowance for full-size pick-up trucks, calculated in accordance with subsection 18.4(1).

Fleet average carbon-related exhaust emission value for the 2011 model year

18.1 (1) The fleet average carbon-related exhaust emission value for the 2011 model year, expressed in grams of CO2 equivalent per mile, is calculated by dividing 8,887 by the company’s fleet average fuel economy for that model year calculated in accordance with the following formula:

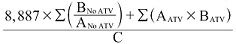

![]()

where

- A is the fuel economy level for each model type, expressed in miles per gallon, determined in accordance with the following provisions, taking into account subsection 19(2):

- (a) in the case of advanced technology vehicles, the provisions of section 208 of Title 40, chapter I, part 600, subpart C, of the CFR, for the model year in question, or

- (b) in all other cases, the provisions of section 510(c)(2) of Title 40, chapter I, part 600, subpart F, of the CFR, for the model year in question;

- B is the number of vehicles of the model type in question in the fleet; and

- C is the total number of vehicles in the fleet.

Fleet average carbon-related exhaust emission value for 2012 and subsequent model years

(2) Subject to subsections (8) to (10), a company must calculate the fleet average carbon-related exhaust emission value for each of its fleets of the 2012 model year and subsequent model years using the following formula:

![]()

where

- A is the following carbon-related exhaust emission value for each model type and includes, if an election is made under subsection 10(2), the exhaust emission for nitrous oxide (N2O) and methane (CH4):

- (a) in the case of electric vehicles and fuel cell vehicles, 0 grams of CO2 equivalent per mile,

- (b) in the case of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles, the value determined in accordance with section 113(n)(2) of Title 40, chapter I, part 600, subpart B, of the CFR for the model year in question, taking into account subsection 19(2) and the following clarifications, and expressed in grams of CO2 equivalent per mile:

- (i) the value in respect of exhaust emissions is determined in accordance with section 510(j)(2) of Title 40, chapter I, part 600, subpart F, of the CFR, and

- (ii) the equivalent value in respect of the electricity grid for the electricity that is used to recharge the energy storage system is equal to 0 grams of CO2 equivalent per mile, or

- (c) in all other cases, the value determined in accordance with section 510(j)(2) of Title 40, chapter I, part 600, subpart F, of the CFR, for the model year in question, taking into account subsection 19(2), and expressed in grams of CO2 equivalent per mile;

- B is the number of vehicles of the model type in question in the fleet; and

- C is the total number of vehicles in the fleet.

Advanced technology

(3) When calculating the fleet average carbon-related exhaust emission value in accordance with subsections (1) and (2) for fleets of the 2011 to 2016 model years, a company may, for the purposes of the descriptions of B and C in subsections (1) and (2), elect to multiply the number of advanced technology vehicles in its fleet by 1.2, if the company reports that election and indicates the number of credits obtained as a result of that election in its end of model year report.

Multiplier for certain vehicles

(4) Subject to subsection (5), when calculating the fleet average carbon-related exhaust emission value in accordance with subsection (2) for fleets of the 2017 to 2025 model years, a company may, for the purposes of the descriptions of B and C in subsection (2), elect to multiply the number of advanced technology vehicles, natural gas vehicles or natural gas dual fuel vehicles in its fleet by the number set out in the following table in respect of that type of vehicle for the model year in question, if the company reports that election and indicates the number of credits obtained as a result of that election and the number of vehicles in question in its end of model year report.

| Item | Column 1 Model Year |

Column 2 Electric Vehicle and Fuel Cell Vehicle Multiplier |

Column 3 Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle Multiplier |

Column 4 Natural Gas Vehicle and Natural Gas Dual Fuel Vehicle Multiplier |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 2017 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 1.6 |

| 2. | 2018 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 1.6 |

| 3. | 2019 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 1.6 |

| 4. | 2020 | 2.25 | 1.95 | 1.45 |

| 5. | 2021 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.3 |

| 6. | 2022 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.0 |

| 7. | 2023 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.0 |

| 8. | 2024 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.0 |

| 9. | 2025 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.0 |

Requirement — plug-in hybrid electric vehicles

(5) A company may make an election under subsection (4) in respect of a plug-in hybrid electric vehicle of the 2017 to 2025 model years only if the vehicle has an all-electric driving range equal to or greater than 16.4 km (10.2 miles) or an equivalent all-electric driving range equal to or greater than 16.4 km (10.2 miles). The all-electric driving range and the equivalent all-electric driving range are determined in accordance with section 1866(b)(2)(ii) of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter C, part 86, subpart S, of the CFR.

Maximum decrease for dual fuel vehicles

(6) For the purposes of subsections (1) and (2) for fleets of the 2011 to 2015 model years, and for the purposes of section 29 for fleets of the 2008 to 2010 model years, if the fleet contains alcohol dual fuel vehicles or natural gas dual fuel vehicles, the fleet average carbon-related exhaust emission value is the greater of

- (a) the fleet average carbon-related exhaust emission value calculated in accordance with subsections (1) and (2), and

- (b) the fleet average carbon-related exhaust emission value calculated in accordance with subsections (1) and (2) with the assumption that all alcohol dual fuel vehicles and natural gas dual fuel vehicles operate exclusively on gasoline or diesel fuel, minus the applicable limit set out in section 510(i) of Title 40, chapter I, part 600, subpart F, of the CFR.

Alternative value

(7) For the purposes of section 510(j)(2)(vi) of Title 40, chapter I, part 600, subpart F, of the CFR, a company may use an alternative value for the weighting factor “F” if the company provides the Minister with evidence demonstrating that the alternative value is more representative of its fleet.

Maximum number — until 2016 model year

(8) For the purposes of paragraphs (a) and (b) of the description of A in subsection (2), a company must replace the carbon-related exhaust emission value, referred to in the description of A in that subsection, with the value determined under subsection (10) for all of the electric vehicles and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles in its fleets of the model year corresponding to the year during which this subsection comes into force, and subsequent model years until the 2016 model year, that are in excess of the following applicable maximum number of advanced technology vehicles:

- (a) 30,000 vehicles, in the case of a company that manufactured or imported less than 3,750 advanced technology vehicles of the 2012 model year for sale in Canada and that has already included 30,000 advanced technology vehicles in its fleets of the 2011 to 2016 model years, or in its fleets of the 2008 to 2016 model years, if the company obtained early action credits in respect of its fleets of the 2008 to 2010 model years; or

- (b) 45,000 vehicles, in the case of a company that manufactured or imported 3,750 or more advanced technology vehicles of the 2012 model year for sale in Canada and that has already included 45,000 advanced technology vehicles in its fleets of the 2011 to 2016 model years, or in its fleets of the 2008 to 2016 model years, if the company obtained early action credits in respect of its fleets of the 2008 to 2010 model years.

Maximum number — 2022 to 2025 model years

(9) For the purposes of paragraphs (a) and (b) of the description of A in subsection (2), a company must replace the carbon-related exhaust emission value, referred to in the description of A in that subsection, with the value determined under subsection (10) for all of the electric vehicles and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles in its fleets of the 2022 to 2025 model years that are in excess of the following applicable maximum number of advanced technology vehicles:

- (a) 30,000 vehicles, in the case of a company that manufactured or imported less than 45,000 advanced technology vehicles of the 2019 to 2021 model years for sale in Canada; or

- (b) 90,000 vehicles, in the case of a company that manufactured or imported 45,000 or more advanced technology vehicles of the 2019 to 2021 model years for sale in Canada.

Electric vehicles and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles in excess of maximum number

(10) For any electric vehicles and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles that are in excess of the applicable maximum number, a company must determine the carbon-related exhaust emission value for the model year in question, taking into account subsection 19(2) and expressing the result in grams of CO2 equivalent per mile, in accordance with

- (a) in the case of electric vehicles, section 113(n)(1) of Title 40, chapter I, part 600, subpart B, of the CFR — excluding the measure for the limited number of vehicles referred to in the description of CREE — except that the description of AVGUSUP in that section is equal to 0.210; and

- (b) in the case of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles, section 113(n)(2) of Title 40, chapter I, part 600, subpart B, of the CFR, taking into account the following clarifications:

- (i) the value in respect of exhaust emissions is determined in accordance with section 510(j)(2) of Title 40, chapter I, part 600, subpart F, of the CFR, and

- (ii) the equivalent value in respect of the electricity grid for the electricity that is used to recharge the energy storage system is determined in accordance with section 113(n)(1) of Title 40, chapter I, part 600, subpart B, of the CFR — excluding the measure for the limited number of vehicles referred to in the description of CREE — except that the description of AVGUSUP in that section is equal to 0.210.

Fuel cell vehicles

(11) For the purposes of subsections (8) and (9), a company must count its fuel cell vehicles first, before counting the other advanced technology vehicles.

Allowance for reduction of air conditioning refrigerant leakage

18.2 (1) A company may elect to calculate, using the following formula, an allowance for the use, in its fleet of passenger automobiles or light trucks, of air conditioning systems that incorporate technologies designed to reduce air conditioning refrigerant leakage:

![]()

where

- A is the CO2 equivalent leakage reduction for each air conditioning system in the fleet that incorporates those technologies, determined in accordance with section 1867 of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter C, part 86, of the CFR and expressed in grams of CO2 equivalent per mile;

- B is the number of passenger automobiles or light trucks in the fleet that are equipped with the air conditioning system; and

- C is the total number of passenger automobiles or light trucks in the fleet.

Allowance for improvement of air conditioning system efficiency

(2) A company may elect to calculate, using the following formula, an allowance for the use, in its fleet of passenger automobiles or light trucks, of air conditioning systems that incorporate technologies designed to reduce air-conditioning-related CO2 emissions by improving air conditioning system efficiency:

![]()

where

- A is the air conditioning efficiency allowance for each air conditioning system in the fleet that incorporates those technologies, determined in accordance with the provisions relating to credits in sections 165, 167 and 1868 of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter C, part 86, of the CFR and expressed in grams of CO2 per mile;

- B is the number of passenger automobiles or light trucks in the fleet that are equipped with the air conditioning system; and

- C is the total number of passenger automobiles or light trucks in the fleet.

Allowance for certain innovative technologies

18.3 (1) Subject to subsection (3), a company may elect to calculate, using the following formula, an allowance for the use, in its fleet of passenger automobiles or light trucks of the 2014 model year and subsequent model years, of innovative technologies that result in a measurable CO2 emission reduction and that are referred to in section 1869(b)(1) of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter C, part 86, of the CFR:

![]()

where

- A is the allowance for each of those technologies that is used in the fleet, determined in accordance with section 1869(b)(1) of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter C, part 86, of the CFR and expressed in grams of CO2 per mile;

- B is the number of passenger automobiles or light trucks in the fleet that are equipped with the innovative technology; and

- C is the total number of passenger automobiles or light trucks in the fleet.

Alternative procedure

(2) Instead of determining the allowance for each innovative technology that is used in the fleet in accordance with the description of A in subsection (1), a company may

- (a) determine that allowance in accordance with the provisions for the 5-cycle methodology set out in section 1869(c) of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter C, part 86, of the CFR, expressed in grams of CO2 per mile;

- (b) use the credit value approved by the EPA for that technology under section 1869(e) of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter C, part 86, of the CFR, expressed in grams of CO2 per mile, if the company provides the Minister with evidence of that approval in its end of model year report; or

- (c) determine that allowance in accordance with an alternative procedure, if the company provides the Minister with evidence demonstrating that the alternative procedure allows for a more accurate determination of the emission reduction attributable to the innovative technology and that the allowance determined in accordance with that procedure more accurately represents that emission reduction.

Maximum allowance — certain innovative technologies

(3) If, for a model year, the total of the allowances for innovative technologies that a company elects to determine, for a single vehicle, in accordance with the description of A in subsection (1) is greater than 10 grams of CO2 per mile, the company must calculate, using the following formula, the allowance for the use, in its fleet of passenger automobiles or light trucks of that model year, of innovative technologies that result in a measurable CO2 emission reduction and that are referred to in section 1869(b)(1) of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter C, part 86, of the CFR:

![]()

where

- A is the allowance for each innovative technology for which an allowance is determined for the purposes of subsection (4);

- B is the number of passenger automobiles or light trucks that are equipped with the innovative technology that is used for the purposes of subsection (4); and

- C is the total number of passenger automobiles or light trucks in the fleet.

Adjustment

(4) For the purposes of subsection (3), the company must perform the following calculation and ensure that the result does not exceed 10 grams of CO2 per mile:

![]()

where

- A is the allowance for each innovative technology that is used in the fleet and that the company decides to take into account, determined in accordance with subsection (1);

- Ba is the number of passenger automobiles in the fleet that are equipped with the innovative technology in question and that the company decides to take into account; and

- Bt is the number of light trucks in the fleet that are equipped with the innovative technology in question and that the company decides to take into account.

Allowance for innovative technologies

(5) A company may elect to calculate, using the following formula, an allowance for the use, in its fleet of passenger automobiles or light trucks, of innovative technologies — other than those referred to in subsection (1) — that result in a measurable CO2 emission reduction:

![]()

where

- A is the allowance for each innovative technology that is used in the fleet, determined in accordance with the provisions for the 5-cycle methodology set out in section 1869(c) of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter C, part 86, of the CFR and expressed in grams of CO2 per mile;

- B is the number of passenger automobiles or light trucks in the fleet that are equipped with the innovative technology; and

- C is the total number of passenger automobiles or light trucks in the fleet.

Alternative procedure to the 5-cycle methodology

(6) If the 5-cycle methodology referred to in subsection (5) cannot adequately measure the emission reduction attributable to an innovative technology, a company may, instead of determining the allowance for the innovative technology in accordance with the description of A in subsection (5),

- (a) use the credit value approved by the EPA for that technology under section 1869(e) of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter C, part 86, of the CFR, expressed in grams of CO2 per mile, if the company provides the Minister with evidence of the EPA approval in its end of model year report; or

- (b) determine that allowance in accordance with an alternative procedure, if the company provides the Minister with evidence demonstrating that the alternative procedure allows for a more accurate determination of the emission reduction attributable to the innovative technology and that the allowance determined in accordance with that procedure more accurately represent that emission reduction.

Allowance for certain full-size pick-up trucks

18.4 (1) Subject to subsections (2) to (4), for fleets of light trucks of the 2017 to 2025 model years, a company may elect to calculate, using the following formula, a CO2 allowance for the presence, in its fleet, of full-size pick-up trucks equipped with hybrid electric technologies and of full-size pick-up trucks that achieve carbon-related exhaust emission values below the applicable target value:

![]()

where

- AH is the allowance for the use of hybrid electric technologies, namely,

- (a) 10 grams of CO2 per mile for mild hybrid electric technologies, or

- (b) 20 grams of CO2 per mile for strong hybrid electric technologies;

- BH is the number of full-size pick-up trucks in the fleet that are equipped with mild hybrid electric technologies or that are equipped with strong hybrid electric technologies, as the case may be;

- AR is the allowance for full-size pick-up trucks that achieve a certain carbon-related exhaust emission value, namely,

- (a) 10 grams of CO2 per mile for full-size pick-up trucks that achieve a carbon-related exhaust emission value that is less than or equal to their applicable target value, determined in accordance with subsection 17(7), multiplied by 0.85 and greater than their applicable target value multiplied by 0.8, or

- (b) 20 grams of CO2 per mile for full-size pick-up trucks that achieve a carbon-related exhaust emission value that is less than or equal to their applicable target value, determined in accordance with subsection 17(7), multiplied by 0.8;

- BR is the number of full-size pick-up trucks in the fleet that achieve a carbon-related exhaust emission value that is within the range referred to in paragraph (a) of the description of AR or that is less than or equal to their applicable target value, determined in accordance with subsection 17(7), multiplied by 0.8, as the case may be; and

- C is the total number of light trucks in the fleet.

Allowance limitations — hybrid electric technologies

(2) The allowance for the use of hybrid electric technologies referred to in paragraphs (a) and (b) of the description of AH in subsection (1) may be calculated in respect of full-size pick-up trucks of a model year only if the percentage in the fleet of full-size pick-up trucks of that model year that are equipped with those technologies is equal to or greater than the percentage for that model year set out in section 1870(a)(1) or (2), depending on the technology used, of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter C, part 86, of the CFR. The allowance referred to in paragraph (a) of the description of AH may be calculated only for full-size pick-up trucks of the 2017 to 2021 model years.

Allowance limitations — carbon-related exhaust emissions performance

(3) The allowance for full-size pick-up trucks that achieve a carbon-related exhaust emission value referred to in paragraphs (a) and (b) of the description of AR in subsection (1) may be calculated in respect of full-size pick-up trucks of a model year only if the percentage in the fleet of full-size pick-up trucks of that model year that achieve such a value is equal to or greater than the percentage for that model year set out in section 1870(b)(1) or (2), depending on the emission performance achieved, of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter C, part 86, of the CFR. The allowance referred to in paragraph (a) of the description of AR may be calculated only for full-size pick-up trucks of the 2017 to 2021 model years.

Single allowance

(4) A company must not claim, in respect of the same pick-up truck, both the allowance referred to in the description of AH in subsection (1) and the allowance referred to in the description of AR in that subsection.

Election

(5) A company that elects to multiply the number of advanced technology vehicles in its fleet in accordance with subsection 18.1(4) must not use the allowance referred to in the description of AR in subsection (1) for the same vehicle.

11. Section 19 of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Interpretation of standards

19. (1) The carbon-related exhaust emission value and the fuel economy level that are calculated in accordance with section 18.1 must be calculated taking into account the applicable test procedures, fuels and calculation methods set out in subpart B of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter C, part 86 and in subpart B of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter Q, part 600, of the CFR and taking into account any clarifications or additional information issued by the EPA, if the company keeps a copy of those clarifications or that additional information.

Representative data

(2) When a company calculates the fleet average carbon-related exhaust emission value under section 18, the data and values used in the calculation must represent at least 90% of the total number of vehicles in the company’s fleet with respect to the configuration.

12. (1)The portion of subsection 20(3) of the Regulations before the word “where” is replaced by the following:

Calculation

(3) Subject to subsections (3.1) and (3.2), a company must calculate the credits or deficits for each of its fleets using the following equation:

![]()

(2) Section 20 of the Regulations is amended by adding the following after subsection (3):

Alternative standard — nitrous oxide

(3.1) For each test group in respect of which a company uses, for any given model year, an alternative standard for nitrous oxide (N2O) under subsection 10(1), the company must use the following formula, expressing the result in megagrams of CO2 equivalent, and add the sum of the results for each test group to the number of credits or deficits calculated in accordance with subsection (3) for the fleet to which the test group belongs:

![]()

where

- A is the total number of passenger automobiles or light trucks in the test group;

- B is the exhaust emission standard for nitrous oxide (N2O) set out in section 1818(f)(1) of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter C, part 86, subpart S, of the CFR, for the applicable model year, expressed in grams per mile;

- C is the alternative exhaust emission standard for nitrous oxide (N2O) to which the company has elected to certify the test group, expressed in grams per mile; and

- D is the assumed total mileage of the vehicles in question, namely,

- (a) 195,264 miles for a fleet of passenger automobiles, or

- (b) 225,865 miles for a fleet of light trucks.

Alternative standard — methane

(3.2) For each test group in respect of which a company uses, for any given model year, an alternative standard for methane (CH4) under subsection 10(1), the company must use the following formula, expressing the result in megagrams of CO2 equivalent, and add the sum of the results for each test group to the number of credits or deficits calculated in accordance with subsection (3) for the fleet to which the test group belongs:

![]()

where

- A is the total number of passenger automobiles or light trucks in the test group;

- B is the exhaust emission standard for methane (CH4) set out in section 1818(f)(1) of Title 40, chapter I, subchapter C, part 86, subpart S, of the CFR, for the applicable model year, expressed in grams per mile;

- C is the alternative exhaust emission standard for methane (CH4) to which the company has elected to certify the test group, expressed in grams per mile; and

- D is the assumed total mileage of the vehicles in question, namely,

- (a) 195,264 miles for a fleet of passenger automobiles, or

- (b) 225,865 miles for a fleet of light trucks.

(3) Subsection 20(5) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Time limit — credits for 2011 to 2016 model years

(5) Credits obtained for a fleet of passenger automobiles or light trucks of the 2011 to 2016 model years may be used in respect of any fleet of passenger automobiles or light trucks of any model year after the model year in respect of which the credits were obtained, until the 2021 model year, after which the credits are no longer valid.

Time limit — credits for 2017 model year and subsequent model years

(6) Credits obtained for a fleet of passenger automobiles or light trucks of the 2017 model year or a subsequent model year may be used in respect of any fleet of passenger automobiles or light trucks of any model year up to five model years after the model year in respect of which the credits were obtained, after which the credits are no longer valid.

13. (1)Subsection 21(2) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Remaining credits

(2) Subject to subsection (2.1), a company may bank any remaining credits to offset a future deficit or transfer the remaining credits to another company, except during the 2012 to 2015, and, if applicable, 2016, model years if the company elects to create a temporary optional fleet under section 24.

Remaining credits — transfer prohibited

(2.1) A company that has made an election under section 28.1 and obtained credits in respect of its fleets of the 2017 to 2020 model years may not transfer any remaining credits to another company.

(2) Subsection 21(4) of the French version of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Rajustement

(4) Le nombre de points obtenu à l’égard de parcs de l’année de modèle 2011 composés en partie de véhicules à alcool à double carburant ou de véhicules à gaz naturel à double carburant qui est disponible pour compenser un déficit à l’égard d’un parc d’automobiles à passagers ou de camions légers de l’année de modèle 2012 ou d’une année ultérieure doit être rajusté à partir de l’hypothèse selon laquelle tous les véhicules à alcool à double carburant et les véhicules à gaz naturel à double carburant fonctionnent seulement à l’essence ou au carburant diesel.

14. The Regulations are amended by adding the following after section 21:

Limit on use of 2011 model year credits

21.1 (1) Despite subsection 21(3), the total number of credits obtained in respect of fleets of the 2011 model year that a company may use to offset a deficit incurred in respect of a fleet of passenger automobiles or light trucks of a given model year or a temporary optional fleet of passenger automobiles or light trucks of a given model year must not exceed the maximum number calculated using the following formula:

![]()

where

- A is the fleet average CO2 equivalent emission standard calculated in accordance with section 16 for the 2011 model year expressed in grams of CO2 equivalent per mile;

- Bharmonic is the fleet average CO2 equivalent emission value calculated in accordance with section 18, expressed in grams of CO2 equivalent per mile, except that the value of D is calculated as follows:

- where

- BNo ATV is the number of vehicles of the model type in question in the fleet, excluding advanced technology vehicles,

- ANo ATV is the fuel economy level for each model type, excluding advanced technology vehicles, expressed in miles per gallon, determined for the 2011 model year in accordance with section 510(c)(2) of Title 40, chapter I, part 600, subpart F, of the CFR, taking into account subsection 19(2),

- AATV is the carbon-related exhaust emission value for each model type of advanced technology vehicles, expressed in grams of CO2 equivalent per mile, determined for the 2011 model year in accordance with section 208 of Title 40, chapter I, part 600, subpart C, of the CFR, taking into account subsection 19(2),

- BATV is the number of advanced technology vehicles of the model type in question in the fleet, and

- C is the total number of passenger automobiles or light trucks in the fleet;

- C is the total number of passenger automobiles or light trucks in the fleet;

- D is the assumed total mileage of the vehicles in question, namely,

- (a) 195,264 miles for a fleet of passenger automobiles, or

- (b) 225,865 miles for a fleet of light trucks; and

- X is the number of credits obtained in respect of fleets of the 2011 model year that have been used by a company to offset a deficit incurred in respect of a fleet of passenger automobiles or light trucks or a temporary optional fleet of passenger automobiles or light trucks of the 2012 model year, expressed in megagrams of CO2 equivalent.

Advanced technology

(2) For the purposes of description of BATV in subsection (1), a company may elect to multiply the number of advanced technology vehicles by 1.2, if the company made that election for the 2011 model year and reported that election in its end of model year report for the 2011 model year.

Representative data

(3) When a company determines the value corresponding to the description of ANoATV and AATV in subsection (1), the data and values used in the calculation must represent at least 90% of the vehicles in question in the company’s fleet with respect to the configuration.

Number of vehicles in fleet

(4) For the purposes of subsection (1), the company must include in its fleet of passenger automobiles or light trucks the same number of vehicles that it included in its fleets for the purposes of its end of model year report for the 2011 model year.

Negative result

(5) For greater certainty, if the result of the calculation set out in subsection (1) in respect of fleets of the 2011 model year is negative, then the total number of credits that a company may use to offset a deficit is zero.

15. The Regulations are amended by adding the following after section 28:

FLEXIBILITY MEASURES FOR THE 2017 TO 2020 MODEL YEARS

CO2 emission target values

28.1 A company that has elected to create a temporary optional fleet under subsection 24(1) and that manufactured or imported in total 750 or more, but less than 7,500, passenger automobiles and light trucks of the 2009 model year for sale in Canada may, when calculating the fleet average CO2 equivalent emission standard under section 17 for fleets of the 2017 to 2020 model years, elect, for a given model year, to replace the CO2 emission target value applicable to a given group of passenger automobiles or light trucks under section 17 with the following, if the company reports that election in its end of model year report:

- (a) in the case of a fleet of passenger automobiles or light trucks of the 2017 or 2018 model year, the CO2 emission target value that would be applicable to that group under section 17 if the passenger automobiles or light trucks included in that group were of the 2016 model year;

- (b) in the case of a fleet of passenger automobiles or light trucks of the 2019 model year, the CO2 emission target value that would be applicable to that group under section 17 if the passenger automobiles or light trucks included in that group were of the 2018 model year; or

- (c) in the case of a fleet of passenger automobiles or light trucks of the 2020 model year, the CO2 emission target value that would be applicable to that group under section 17 if the passenger automobiles or light trucks included in that group were of the 2019 model year.

Merger

28.2 For the purposes of section 28.1, in the case of a company that merges with one or more companies after December 31, 2009, the total number of passenger automobiles and light trucks of the 2009 model year manufactured or imported for sale in Canada by the company is the sum of the number of passenger automobiles and light trucks of the 2009 model year manufactured or imported for sale in Canada by each of the merged companies.

Purchase

28.3 For the purposes of section 28.1, in the case of a company that purchases one or more companies after December 31, 2009, the total number of passenger automobiles and light trucks of the 2009 model year manufactured or imported for sale in Canada by the company is the sum of the number of passenger automobiles and light trucks of the 2009 model year manufactured or imported for sale in Canada by the company and all purchased companies.

16. Subsection 29(6) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Time limit — credits for the 2009 model year

(6) Early action credits obtained for a fleet of passenger automobiles or light trucks of the 2009 model year may be used in respect of any fleet of passenger automobiles or light trucks of the 2011 to 2014 model years, after which the credits are no longer valid.

Time limit — credits for the 2010 model year

(6.1) Early action credits obtained for a fleet of passenger automobiles or light trucks of the 2010 model year may be used in respect of any fleet of passenger automobiles or light trucks of the 2011 to 2021 model years, after which the credits are no longer valid.

17. (1)Subparagraph 31(2)(a)(ii) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

- (ii) the fleet average carbon-related exhaust emission value, calculated in accordance with subsection 18.1(1), and the values and data used in the calculation of that value,

(2) The portion of paragraph 31(3)(h) of the Regulations before subparagraph (i) is replaced by the following:

- (h) if the company calculates an allowance referred to in subsection 18.2(1), the value of the allowance for the fleet and, for each air conditioning system,

(3) The portion of paragraph 31(3)(i) of the Regulations before subparagraph (i) is replaced by the following:

- (i) if the company calculates an allowance referred to in subsection 18.2(2), the value of the allowance for the fleet and, for each air conditioning system,

(4) Paragraph 31(3)(j) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

- (j) if the company calculates an allowance referred to in subsection 18.3(5), the value of the allowance for the fleet and, for each innovative technology,

- (i) a description of the technology,

- (ii) the allowance for each innovative technology, determined in accordance with that subsection and, if applicable, subsection 18.3(6), and the values and data used in the calculation of the allowance, and

- (iii) the total number of vehicles in the fleet that are equipped with the technology; and

18. Section 32 of the Regulations is repealed.

19. (1)Subsection 33(2) of the Regulations is amended by adding the following after paragraph (b):

- (b.1) if applicable, a statement that the company has elected to exclude emergency vehicles from its fleets of passenger automobiles and light trucks;

(2) Paragraph 33(2)(d) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

- (d) the CO2 emission target value for each group, determined for the purposes of section 17, and the values and data used in the calculation of that value;

(3) Paragraph 33(2)(i) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

- (i) the carbon-related exhaust emission value for each model type, calculated in accordance with subsection 18.1(2), and the values and data used in the calculation of that value;

- (i.1) if applicable, evidence demonstrating that the alternative value for the weighting factor “F” referred to in subsection 18.1(7) is more representative of the company’s fleet;

(4) Paragraphs 33(2)(l) to (o) of the Regulations are replaced by the following:

- (l) if the company calculates an allowance referred to in subsection 18.2(1), the value of the allowance for the fleet and, for each air conditioning system,

- (i) a description of the system,

- (ii) the CO2 equivalent leakage reduction, determined in accordance with that subsection, and the values and data used in the calculation of the reduction, and

- (iii) the total number of vehicles in the fleet that are equipped with the system;

- (m) if the company calculates an allowance referred to in subsection 18.2(2), the value of the allowance for the fleet and, for each air conditioning system,

- (i) a description of the system,

- (ii) the air conditioning efficiency allowance, determined in accordance with that subsection, and the values and data used in the calculation of the allowance, and

- (iii) the total number of vehicles in the fleet that are equipped with the system;

- (m.1) if the company calculates an allowance referred to in subsection 18.3(1), the value of the allowance for the fleet and, for each innovative technology,

- (i) a description of the technology,

- (ii) the allowance for that technology, determined in accordance with subsection 18.3(1) or (2), the values and data used in the calculation of the allowance and, if applicable, evidence of the EPA approval referred to in paragraph 18.3(2)(b) or the evidence referred to in paragraph 18.3(2)(c), and

- (iii) the total number of vehicles in the fleet that are equipped with the technology;

- (n) if the company calculates an allowance referred to in subsection 18.3(5), the value of the allowance for the fleet and, for each innovative technology,

- (i) a description of the technology,

- (ii) the allowance for that technology, determined in accordance with subsection 18.3(5) or (6), the values and data used in the calculation of the allowance, and, if applicable, evidence of the EPA approval referred to in paragraph 18.3(6)(a) or the evidence referred to in paragraph 18.3(6)(b), and

- (iii) the total number of vehicles in the fleet that are equipped with the technology;

- (o) if the company calculates an allowance referred to in subsection 18.4(1), the value of the allowance for the fleet and the values and data used in the calculation of the allowance;

(5) Paragraph 33(2)(q) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

- (q) if applicable, a statement that the company has elected to apply subsection 18.1(3) and an indication of the number of credits obtained as a result of this election and of the number of vehicles in question;

- (q.1) if applicable, a statement that the company has elected to apply subsection 18.1(4) and an indication of the number of credits obtained as a result of this election and of the number of vehicles in question;

(6) Subsection 33(2) of the Regulations is amended by striking out “and” at the end of paragraph (s) and by adding the following after paragraph (s):

- (s.1) if applicable, a statement that the company has elected to apply section 28.1, an indication of the total number of passenger automobiles and light trucks of the 2009 model year that were manufactured or imported for sale in Canada by the company and

- (i) if the company results from a merger that took place after December 31, 2009, an indication of the total number of passenger automobiles and light trucks of the 2009 model year that were manufactured or imported for sale in Canada by each company involved in the merger, and

- (ii) if the company purchased one or more companies after December 31, 2009, an indication of the total number of passenger automobiles and light trucks of the 2009 model year that were manufactured or imported for sale in Canada by each company it purchased; and

(7) Paragraph 33(3)(a) of the Regulations is amended by adding the following after subparagraph (i):

- (i.1) the company has elected to exclude emergency vehicles from its temporary optional fleets,

(8) Paragraph 33(3)(c) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

- (c) the CO2 emission target value for each group, determined for the purposes of section 17, and the values and data used in the calculation of that value;

(9) Paragraph 33(3)(h) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

- (h) the carbon-related exhaust emission value for each model type, calculated in accordance with subsection 18.1(2), and the values and data used in the calculation of that value;

(10) Paragraphs 33(3)(j) to (l) of the Regulations are replaced by the following:

- (j) if the company calculates an allowance referred to in subsection 18.2(1), the value of the allowance for the temporary optional fleet and, for each air conditioning system,

- (i) a description of the system,

- (ii) the CO2 equivalent leakage reduction, determined in accordance with that subsection, and the values and data used in the calculation of the reduction, and

- (iii) the total number of vehicles in the temporary optional fleet that are equipped with the system;

- (k) if the company calculates an allowance referred to in subsection 18.2(2), the value of the allowance for the temporary optional fleet and, for each air conditioning system,

- (i) a description of the system,

- (ii) the air conditioning efficiency allowance, determined in accordance with that subsection, and the values and data used in the calculation of the allowance, and

- (iii) the total number of vehicles in the temporary optional fleet that are equipped with the system;

- (k.1) if the company calculates an allowance referred to in subsection 18.3(1), the value of the allowance for the temporary optional fleet and, for each innovative technology,

- (i) a description of the technology,

- (ii) the allowance for that technology, determined in accordance with subsection 18.3(1) or (2), the values and data used in the calculation of the allowance and, if applicable, evidence of the EPA approval referred to in paragraph 18.3(2)(b) or the evidence referred to in paragraph 18.3(2)(c), and

- (iii) the total number of vehicles in the temporary optional fleet that are equipped with the technology;

- (l) if a company calculates an allowance referred to in subsection 18.3(5), the value of the allowance for the temporary optional fleet and, for each innovative technology,

- (i) a description of the technology,

- (ii) the allowance for that technology, determined in accordance with subsection 18.3(5) or (6), the values and data used in the calculation of the allowance and, if applicable, evidence of the EPA approval referred to in paragraph 18.3(6)(a) or the evidence referred to in paragraph 18.3(6)(b), and

- (iii) the total number of vehicles in the temporary optional fleet that are equipped with the technology;

20. Section 35 of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Declaration — subsection 14(1) or paragraph 14(1.1)(d)

35. (1) For the purposes of subsection 14(1) or paragraph 14(1.1)(d), a company must submit a declaration to the Minister, signed by a person who is authorized to act on behalf of the company, no later than May 1 of the calendar year that corresponds to the model year in respect of which the company does not wish to be subject to sections 13 and 17 to 20, and must specify in the declaration the total number of passenger automobiles and light trucks manufactured or imported for sale in Canada for each model year in question.

Declaration — paragraphs 14(1.1)(a) to (c)

(2) For the purposes of paragraphs 14(1.1)(a) to (c), a company must submit a declaration to the Minister, signed by a person who is authorized to act on behalf of the company, no later than May 1 of the calendar year that corresponds to two, three or four model years, as the case may be, following the first model year for which the company manufactures or imports passenger automobiles or light trucks for sale in Canada, and must specify in the declaration the total number of passenger automobiles and light trucks manufactured or imported for sale in Canada for the model year in question.

21. (1)Paragraphs 39(1)(d) and (e) of the Regulations are replaced by the following:

- (d) the values and data used in calculating the fleet average CO2 equivalent emission value, including information relating to the calculation of allowances;

- (e) if applicable, a copy of the clarifications or additional information referred to in subsection 19(1); and

- (f) the values used to calculate the CO2 emission credits, the credits obtained in respect of a temporary optional fleet and the early action credits.

(2) Paragraph 39(2)(c) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

- (c) in the case of a vehicle covered by an EPA certificate, the applicable test group identified in the application for the EPA certificate;

(3) Paragraph 39(2)(f) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

- (f) the applicable carbon-related exhaust emission value and the values and data used in calculating that value;

- (f.1) in the case of a full-size pick-up truck in respect of which an allowance is calculated in accordance with subsection 18.4(1) for the use of a mild or strong hybrid electric technology, a description of the hybrid electric technology; and

22. Section 44 of the Regulations is amended by adding the following after subsection (3):

Applicable standard — sub-configuration

(4) For the purposes of subsection (3), if the carbonrelated exhaust emission value for a subconfiguration of the model type in question was used in the calculation under subsection 18.1(2), the prescribed standard that applies to a vehicle is the product of 1.1 multiplied by the carbon-related exhaust emission value for that subconfiguration.

23. The Regulations are amended by replacing “18(3)” with “18.1(2)” in the following provisions:

- (a) subsection 10(2);

- (b) paragraphs 31(3)(d) and (f);

- (c) paragraphs 33(2)(h) and 33(3)(g); and

- (d) subsection 44(3).

24. The Regulations are amended by replacing “18(10)” with “18.3(6)” in the following provisions:

- (a) paragraph 31(3)(k); and

- (b) paragraph 33(3)(m).

25. The Regulations are amended by replacing “the coming into force of these Regulations” and “the day on which these Regulations come into force” with “September 23, 2010” in the following provisions:

- (a) subsection 27(1);

- (b) subsection 28(1); and

- (c) subparagraph 33(3)(a)(iii).

COMING INTO FORCE

26. (1)Sections 2 to 6, subsections 12(1) and (2) and sections 14 and 18 come into force on the day on which these Regulations are registered.

(2) Sections 1 and 7 to 11, subsection 12(3) and sections 13, 15 to 17 and 19 to 25 come into force six months after the day on which these Regulations are registered.

REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS STATEMENT

(This statement is not part of the Regulations.)

1. Executive summary

Issues: Greenhouse gases (GHGs) are primary contributors to climate change. The most significant sources of anthropogenic GHG emissions are a result of the combustion of fossil fuels, including gasoline and diesel. In 2009, Canada signed the Copenhagen Accord, committing to reduce its GHG emissions to 17% below 2005 levels by 2020, establishing a target of 607 megatonnes (Mt) of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e). This mirrors the reduction target set by the United States. Canada has a long-standing policy of aligning transportation emissions standards with those of the United States. Alignment provides significant environmental and economic benefits to Canada while minimizing costs to industry and consumers.

The transportation sector is a significant source of GHG emissions in Canada, accounting for 24% of total emissions in 2010.

(see footnote 2) In that year, passenger automobiles and light trucks (hereinafter referred to as light-duty vehicles) accounted for approximately 13% of Canada’s total GHG emissions or 53% of transportation emissions.

Description: The Regulations Amending the Passenger Automobile and Light Truck Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations (covering model years 2017 and beyond) [hereinafter referred to as the amended Regulations] build on the success of the Passenger Automobile and Light Truck Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations (hereinafter referred to as the current Regulations) covering model years 2011 through 2016. They have been developed in collaboration with the United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) to ensure alignment of Canada’s regulations with those of the United States in a manner that is consistent with the authorities provided under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA 1999). The amended Regulations continue to apply to companies that manufacture or import new light-duty vehicles into Canada for the purpose of sale. Similar to the current Regulations, the amended Regulations establish progressively more stringent annual fleet average GHG emission standards over the 2017 to 2025 model years, while providing companies with flexibility mechanisms to allow them to comply in a cost-effective manner.

Cost-benefit statement: Over the lifetime operation of all 2017 to 2025 model year light-duty vehicles sold in Canada, the amended Regulations are estimated to result in a cumulative reduction of 174 Mt of CO2e in GHG emissions (or an average incremental reduction of 19.3 Mt of CO2e per model year).

(see footnote 3) The present value of benefits from the amended Regulations is estimated to be Can$60.3 billion.

(see footnote 4) The benefits quantified include pre-tax fuel savings, reduced refuelling time, additional driving and reduced GHG emissions. The present value of costs from the amended Regulations is estimated to be $11.2 billion. This includes costs to consumers (incremental technology costs) and costs to Government (vehicle testing, compliance promotion, enforcement and administration). Both benefits and costs are increased due to the “rebound effect,” which is the additional driving or mobility associated with a reduction in driving costs. The rebound effect provides additional benefits to vehicle owners in the form of increased vehicle-kilometres driven, but can also increase costs to society due to increased traffic congestion, motor vehicle crashes, and noise. The present value of net benefits of the amended Regulations is estimated to be $49 billion. Overall, the total benefits exceed total costs by a ratio of over five to one.

The amended Regulations are anticipated to increase the cost of manufacturing light-duty vehicles, which is expected to be passed on directly to consumers purchasing these vehicles. For example, the amended Regulations will add an additional $733 to the average purchase price of a 2021 model year vehicle, rising to an additional $1,829 for a 2025 model year vehicle, as compared to the baseline, in the absence of the amended Regulations (i.e. a continuation of the standards for 2016 model year vehicles).(see footnote 5) The benefits resulting directly from the amended Regulations include fuel savings of approximately 75 billion litres over the lifetime of the 2017 to 2025 model year vehicles. It is estimated that the added costs to these vehicles will be more than offset by fuel savings, with a payback period of between one to three years.

“One-for-One” Rule and small business lens: Environment Canada (EC) has reviewed the administrative burden imposed by the current Regulations in an attempt to identify areas in which the burden could be reasonably reduced. As of the coming into force of the amended Regulations, companies are no longer required to submit an annual preliminary model year report, which represents a noticeable decrease in their administrative burden. Companies are still required to submit annual end of model year reports to enable Environment Canada to assess individual company compliance with the amended Regulations; however these changes result in a net decrease in regulatory burden. Therefore, the amended Regulations are considered an “OUT” under the rule and are estimated to cost Can$59,190, or Can$2,573 per business. The regulated community comprises manufacturers and importers of new light-duty vehicles sold in Canada. All of the companies to which the current Regulations apply are Canadian branches of multinational corporations, and as a result, the spirit of the small business lens does not apply.

Domestic and international coordination and cooperation: The standards for GHG emissions from new light-duty vehicles of model years 2017 through 2025 have been developed in cooperation with the U.S. EPA, continuing a harmonized Canada-United States regulatory approach.The alignment approach is consistent with the Regulatory Cooperation Council’s Joint Action Plan, announced by Prime Minister Harper and President Obama on December 7, 2011, which establishes an enhanced level of regulatory cooperation and alignment between Canada and the United States. The amended Regulations also reflect the global trend towards the regulation of improved automotive fuel economy and GHG emission reductions.

Performance measurement and evaluation: The Performance Measurement and Evaluation Plan (PMEP) describes the desired outcomes of the amended Regulations, such as GHG emissions reductions, and establishes indicators to measure and evaluate the performance of the amended Regulations in achieving these outcomes. The measurement and evaluation will be tracked on a yearly basis, with a five-year compilation assessment, and will be based on the information and data submitted in accordance with the reporting requirements and records of the companies.

2. Background

In 2009, the Government of Canada committed in the Copenhagen Accord to reducing total GHG emissions by 17% from 2005 levels by 2020, a national target that mirrors that of the United States. This target was reaffirmed by the Government of Canada in the Cancun Agreements in 2010.

The Government of Canada has a plan to reduce national GHG emissions based on a sector-by-sector regulatory approach. Taking action to reduce GHG emissions from new light-duty vehicles is an important element of the Government’s plan to introduce an integrated, nationally consistent approach to reduce GHG emissions, in order to achieve its Copenhagen 2020 target.

In October 2010, the Government of Canada published the current Regulations covering new light-duty vehicles of model years 2011 through 2016, under CEPA 1999. These Regulations prescribe progressively more stringent annual emission standards for new light-duty vehicles of model years 2011 to 2016, in alignment with those of the United States.(see footnote 6) As a result of these Regulations, it is projected that the average GHG emission performance of new light-duty vehicles for the 2016 model year will be about 25% better than 2008 model year vehicles sold in Canada. Also in October 2010, the Government of Canada published a Notice of Intent(see footnote 7) to continue working with the United States and build upon the standards already in place to develop more stringent GHG emission standards for new light-duty vehicles of model years 2017(see footnote 8) and beyond.

In November 2011, Environment Canada released a consultation document (see footnote 9) related to the development of the amended Regulations. The document described the key elements being considered for inclusion in the amended Regulations and sought early input from interested parties, for a 30-day period.

In December 2012, the Government of Canada published the proposed Regulations in the Canada Gazette, Part I, which initiated a formal 75-day comment period. Environment Canada considered all comments received during the comment period in developing the amended Regulations.

The automotive manufacturing sector includes motor vehicle manufacturing, motor vehicle body and trailer manufacturing, and motor vehicle parts manufacturing. The automotive manufacturing sector is Canada’s largest manufacturing sector, is highly integrated with the United States and Mexico, and is labour- and capital-intensive. In 2010, the Canadian automotive sector employed 109 300 Canadians. Eighty-two percent of those jobs were located in Ontario. An additional 332 000 workers are employed in the aftermarket and dealerships across Canada.

In 2010, the automotive manufacturing sector accounted for over 12% of manufacturing GDP and 1.5% of Canada’s total GDP. (see footnote 10) Canada exports almost 90% of the vehicles produced in Canada to the United States. (see footnote 11) Export-oriented Canadian automotive assemblers include General Motors, Ford, Chrysler, Toyota, and Honda.

Within the automotive manufacturing sector at large, the automobile and light-duty motor vehicle manufacturing sector (see footnote 12) directly employed approximately 29 000 people in 2010. Also in 2010, auto manufacturing exports totalled $37.5 billion while auto manufacturing imports totalled $30 billion, reflecting a trade surplus of $7.5 billion. In 2008, the Canadian light-duty and heavy-duty vehicle manufacturing sector accounted for about 16% of North American vehicle production, and domestic sales represented 10% of the North American market. (see footnote 13)

3. Issues

Greenhouse gases are primary contributors to climate change. The most significant sources of anthropogenic GHG emissions are a result of the combustion of fossil fuels, including gasoline and diesel fuel. Anthropogenic emissions of GHGs have been increasing significantly since the industrial revolution. This trend is likely to continue unless significant action is taken. In Canada, 80% of total national GHG emissions are associated with the production and consumption of fossil fuels for energy purposes.(see footnote 14) Canada is a vast country with a diverse climate, which makes the impacts of climate change all the more important.

Vol. 148, No. 21 — October 8, 2014

According to the International Energy Agency, Canada’s CO2 emissions from fuel combustion in 2009 accounted for approximately 2% of global emissions. Canada’s share of total global emissions, like that of other developed countries, is expected to continue to decline in the face of rapid emissions growth from developing countries. (see footnote 15) In 2010, Canada’s GHG emissions totalled 692 Mt. Canada is moving forward to regulate GHGs on a sector-by-sector basis, aligning with the United States where appropriate. The Government of Canada has started with the transportation and electricity sectors — two of the largest sources of Canadian emissions — and plans to move forward with regulations in partnership with other key economic sectors.

Transportation is a significant source of GHG emissions in Canada. In 2010, (see footnote 16) 24% of total Canadian GHG emissions came from transportation sources (air, marine, rail, road and other modes). In that year, light-duty vehicles accounted for approximately 13% of Canada’s total GHG emissions or 53% of transportation emissions. Given that there are over 18 million light-duty vehicles on Canadian roads, they are a major contributor to GHG emissions in Canada. (see footnote 17)

4. Objectives

The Government of Canada is taking action to reduce GHG emissions from new light-duty vehicles. The amended Regulations are a key initiative with the objective of addressing climate change, protecting the environment and supporting the deployment of technologies that reduce GHG emissions.