Canada Gazette, Part I, Volume 151, Number 28: Regulations Amending the Canadian Aviation Regulations (Unmanned Aircraft Systems)

July 15, 2017

- Statutory authority

Aeronautics Act - Sponsoring department

Department of Transport

REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS STATEMENT

(This statement is not part of the Regulations.)

Executive summary

Issues: There are three issues associated with a rapidly growing and evolving unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) industry in Canada lacking a mature safety and aviation knowledge culture: the overarching safety issue, the lack of regulatory predictability to foster further development of the UAS industry, and the increase in special flight operations certificate (SFOC) applications that results in an administrative burden.

Description: The Regulations Amending the Canadian Aviation Regulations (Unmanned Aircraft Systems) [the proposed Regulations] would apply primarily to UAS that include unmanned aircraft (UA) weighing more than 250 g but not more than 25 kg and operated within visual line-of-sight (VLOS). They would introduce requirements for UAS users commensurate to the level of risk of a UAS operation based on the weight of the UA, the operating environment and the complexity of the operation, by distinguishing very small UA (more than 250 g but not more than 1 kg) from small UA (more than 1 kg but not more than 25 kg), operated in a limited (rural) or complex (urban) environment. They would also set out the requirements in the areas of licensing, insurance, training and manufacturing, based on the type of UAS.

Cost-benefit statement: The total estimated costs are $172 million in present value (PV) over 10 years with the base year of 2018. (see footnote 1) The majority of the costs are attributed to UAS pilot permit applications and knowledge requirements, insurance requirements for the recreational users and for UAS operators who may be non-compliant with the current regulatory requirements. The qualitative benefits include the safety benefit of reduced risk of incidents or accidents with manned aircraft or with people or property. The monetized benefit of an estimated $111 million PV is due to the cost savings of reduced SFOC applications for both industry and government. The net cost estimate is $61 million PV; however, the overall regulatory proposal is deemed beneficial given the reduced risk of a manned aircraft accident.

“One-for-One” Rule and small business lens: The “One-for-One” Rule applies. The total administrative cost decrease would be an “OUT” with an annualized value of $5.43 million. The proposed amendment does increase compliance costs for small businesses since many of the businesses are assumed to be currently non-compliant with the SFOC process.

Background

The Canadian and global civil aviation system is historically predicated on the notion of having a pilot on board an aircraft and operating the aircraft. However, the ongoing integration of unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) to the civil aviation system creates challenges because unmanned aircraft (UA) are designed to be flown without a pilot on board, by remote control using an external device such as a remote control station, tablet, laptop, smart phone, etc. UAs (see footnote 2) are known in popular culture under various names; examples of such names include unmanned aircraft vehicle (UAV), drone, and remote control (RC) aircraft (RC aircraft, RC plane or RC models). The absence of a pilot from the aircraft raises important technical and operational issues such as the ability to sense and avoid other aircraft. Many small UAs are relatively inexpensive, require little or no set-up or assembly, and are relatively easy to fly, resulting in an influx of people who are unfamiliar with best practices and regulatory requirements within aviation. As a result, the number of recreational and non-recreational users of small UAs has exploded in recent years, thus raising safety concerns while illustrating the potential of this relatively new and growing aviation sector.

Canada currently has a growing and maturing UAS industry focused on operational services such as aerial photography, surveying, and inspection for a number of industries such as film and marketing, agricultural and natural resources, construction, and real estate. Government agencies are also increasingly interested in using UASs whether for ice reconnaissance, northern sovereignty, law enforcement, search and rescue, forest firefighting, or disaster response. Canada's UAS industry is also expanding in the sectors of manufacturing and research and development (R&D). The growth of the UAS industry in Canada is being driven by a number of global and domestic trends, including rapid technological advancement, increasing availability of UAS to the general public, and a broad range of industry sectors in which a UA could facilitate work tasks more efficiently in some cases than manned aviation (e.g. power-line surveys) or more safely than workers exposing themselves to risks of falls or other hazards (e.g. bridge or high-rise inspections). The growth of the UAS industry also has a positive impact on the environment. In the agriculture business, a UAS can assess more precisely where pesticides are needed, thus reducing the quantity of pesticides that are used.

Canadian civil aviation is the responsibility of the Minister of Transport under the Aeronautics Act (AA), which provides the Minister with the authority to develop regulatory requirements under the Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs).

Currently, the CARs have separate definitions and requirements for UAs operated recreationally, defined as “model aircraft,” and UAVs for all non-recreational purposes. The intended non-recreational use of the unmanned aircraft is primarily what differentiates a UAV from a model aircraft.

In contrast to model aircraft, UAVs are used for non-recreational purposes, including business or academic operations such as aerial photography, surveying, agriculture, observation, advertising and research and development. Under the current regulations, UAV operators require an SFOC and they must operate in accordance with all of the conditions listed in the SFOC. The conditions are designed to mitigate safety risks to other airspace users (pilots and passengers in the traditional aviation sector) and to people and property on the ground. Operating without an SFOC or breaching one of the conditions is a designated offence under the CARs where a fine can be issued.

The Interim Order Respecting the Use of Model Aircraft (the Interim Order), first made by the Minister of Transport in March 2017, implemented temporary restrictions on UASs operated recreationally. Within the first two months of issuing the Interim Order, Transport Canada has received feedback from UAS operators regarding where they can operate legally and the restrictiveness of the imposed distances from aerodromes, buildings and people.

Two of the identified requirement gaps for both the recreational and non-recreational UA pilots are systematic training and knowledge standards. Due to the type of incidents involving UAs operating around airports and the lengthy back and forth with many applicants to process SFOCs, it is assumed that the aviation knowledge level and experience of most UAS pilots are generally low.

In working with the current regulatory framework, for non-recreational UAS pilots/operators, SFOCs are issued on a case-by-case basis beginning with site-specific certificates and graduating to broader geographical regions once the operator has established a safety track record with Transport Canada.

Issues

Overarching safety issue

The exponential use of UASs both non-recreationally and recreationally over the past five years has led to an increase in the risk of damage to property and injury to people on the ground and water, and to manned aircraft while taking off or landing.

Risks are largely due to lack of understanding and working knowledge of airspace, aviation regulations, manned aviation airspace users, and best practices. Even with an extensive promotional campaign, it was evident to Transport Canada while processing SFOCs that awareness and understanding of airspace and operator responsibilities is lacking. Ongoing safety incidents involving recreational users suggest that knowledge is also a problem for recreational fliers who are not members of established organizations with education and safety programs, such as the Model Aeronautics Association of Canada (MAAC).

Risk analysis and incidents experienced over the last few years lead Transport Canada to conclude that the risks would not necessarily be attributed to the type of UAS user (i.e. recreational or non-recreational); rather, the higher risks would be associated to the weight of the UAS and to its location of operation.

Administrative burden increase and reduced service standard

Since SFOCs are issued per operation, for example for a building inspection, or in some cases per year for established UAS users, the administrative burden of applying for an SFOC is recurrent. Therefore, the increase in non-recreational UAS use increased the cost associated with the administrative burden.

The increase in non-recreational UAS use has also overwhelmed the UAS SFOC approval system. Transport Canada is no longer able to meet its 20-day service standard for the processing and issuance of SFOCs, even with two general exemptions in place against the requirement for non-recreational UAS operators to seek an SFOC provided they meet specific conditions. Operational delays for businesses are having adverse effects on the industry's ability to plan operations and pursue business opportunities, while Transport Canada's resources are currently diverted from preventive oversight and surveillance programs, including those for traditional aviation.

A non-regulatory approach of UAS safety education and outreach was put in place in November of 2014 when general exemptions were issued to alleviate the requirement to apply for an SFOC for low-risk UAS use. The safety education and outreach campaign (see footnote 3) has been well received by the public and industry, but incidents continue to occur. In addition to the continued safety concern, the SFOC process remains burdensome for industry and Transport Canada.

Regulatory predictability issue

Besides generating significant administrative and compliance burden for applicants and work for Transport Canada, the case-by-case approach of SFOC processing inevitably leads to inconsistencies in when an applicant would receive authorization to operate and in the operating limits and allowances afforded to each UAS operator. These inconsistencies have also been observed from one region to another and within each region in Canada, often causing confusion and frustration. Regulatory predictability would allow a business to plan and commit to services to its clientele with the knowledge that it would be able to comply with the regulatory scheme and operate within it. For a recreational UAS user, it would mean that they would know they could go out and enjoy the activity safely and in compliance with the regulatory scheme. Regulatory predictability is important for development of the UAS industry in Canada and could provide a more stable business planning environment for small UAS operations, sales, testing, and development.

Objectives

The main objective of the regulatory proposal is to mitigate potential safety risks posed by UASs to manned aviation and to people and property on the ground. In addition, Transport Canada has the objectives of

- Improving regulatory predictability in order to foster a stable yet agile regulatory environment for UAS industry development;

- Reducing administrative burden on UAS businesses; and

- Increasing Transport Canada's ability to meet its service standard for traditional aviation activities and surveillance capability.

Description

The focus of the proposed regulatory amendment are UASs weighing more than 250 g but not more than 25 kg, being operated within visual line-of-sight (VLOS). A person who operates a UA that weighs less than 250 g would not be subject to the proposed Regulations. However, this would not relieve any person who operates a UAS of the obligation to respect privacy laws and operate so as not to endanger life or property of any person.

The proposed amendment introduces defined operating categories based on the weight of the UA model as well as the physical operating environment. The proposed Regulations intentionally do not distinguish between recreational and non-recreational operations since the risks they pose are considered the same. Recreational operations that would be impacted by this amendment include the recreational operations that are currently required to adhere to the Interim Order and the existing “model aircraft” category operated under the auspices of MAAC. The term non-recreational operations captures operations by academic institutions for research purposes and government entities such as municipal police; both of which are considered non-recreational where a person or organization will use the UAS for a service to others for a fee. The definitions of both “model aircraft” and “unmanned air vehicle” as currently found in the CARs would be replaced with that of “unmanned aircraft systems.”

Three UAS operating categories are proposed to mitigate the risks by requiring increasingly more stringent requirements as the weight of the UA increases, as well as the areas of operation.

| Micro | Very Small | Small (Limited) | Small (Complex) | Large/Beyond Visual Line-of-Sight (BVLOS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 250 g or less | More than 250 g to 1 kg | More than 1 kg to 25 kg | More than 1 kg to 25 kg | More than 25 kg |

UA of more than 250 g but not more than 25 kg

The following requirements, for example, would apply to all UAS pilots/operators irrespective of the weight of the UA and areas of operation:

- Clearly mark the UA with the name, address and telephone number of the operator;

- Notify air traffic control if the UA inadvertently enters or is likely to enter controlled airspace;

- Operate in manner that is not reckless or negligent (that could not endanger life or property);

- Give right of way to manned aircraft;

- Use another person as a visual observer if using a device that generates a streaming video also known as a first-person view (FPV) device;

- Confirm that no radio interference could affect the flight of the UA;

- Do not operate in cloud; and

- Have liability insurance of at least $100,000.

UA of more than 250 g but not more than 1 kg (very small)

It is proposed that a recreational or non-recreational UA pilot who operates a UA that weighs between 250 g and 1 kg and who operates it anywhere must adhere to the following requirements and limits including, but not limited to:

- (1) Pass a written knowledge test (similar to a boating (see footnote 4) test) to demonstrate aeronautical knowledge in specific subject areas, such as airspace classification and structure, the effects of weather and other areas;

- (2) Be at least 14 years of age;

- (3) Operate at the following minimum distance from an aerodrome: 3 nautical miles (NM) [5.56 km] from the centre of the aerodrome. The required distance from heliports and/or aerodromes used exclusively by helicopters would be 1 NM (1.85 km);

- (4) Operate at least 100 feet (30.5 m) from a person. A distance of less than 100 feet laterally would be possible for operations if conditions such as a reduced maximum permitted speed of 10 knots (11.5 mph) and a minimum altitude of 100 feet are respected;

- (5) Operate at a maximum distance of 0.25 NM (0.46 km) from the pilot;

- (6) Operations over or within open-air assemblies of persons (see footnote 5) would not be allowed;

- (7) Operate below 300 feet;

- (8) Operate at less than 25 knots (29 mph); and

- (9) Night operations would not be allowed.

UA of more than 1 kg but not more than 25 kg (small)

If a person intends to operate a UA that weighs more than 1 kg (2.2 lb.) but not more than 25 kg (55.1 lb.), it is proposed that they comply with increasingly stringent requirements depending on where they operate. Operation of a UA this size in a rural location (see footnote 6) would be referred to as a “limited operation,” whereas in a built-up area, near an aerodrome or within controlled airspace, as a “complex operation.”

For the purposes of these proposed Regulations, a definition of the term built-up area (see footnote 7) is proposed and would allow a person to be able to identify if they are in a built-up area. In addition to specific requirements/limitations pertaining to either a limited or complex operation, some common requirements are proposed. A person who wants to operate a small UA, for example, would be required to perform a site survey prior to launch to identify any obstacles and keep maintenance and flight records.

Small UA (limited operations)

If a person wants to operate a UA that weighs more than 1 kg but not more than 25 kg in an environment with a lower population and less air traffic (generally referred to as a “rural area”), it is proposed that they must adhere to the following requirements and limits, including, but not limited to:

- (1) Pass a written knowledge test (similar to a boating test) to demonstrate aeronautical knowledge in specific subject areas, such as airspace classification and structure, the effects of weather and other areas;

- (2) Be at least 16 years of age;

- (3) Operate at the following minimum distance from an aerodrome: 3 NM (5.56 km) or greater, respecting the control zone; or 1 NM (1.85 km) if there is no control zone. The required distance from heliports and/or aerodromes used exclusively by helicopters would be 1 NM (1.85 km);

- (4) Operate at least 250 feet (76.20 m) from a person. A lateral distance of less than 250 feet would be possible for operations if conditions such as a maximum permitted speed of 10 knots (11.5 mph) and a minimum altitude of 250 feet are respected;

- (5) Operate at a minimum distance of 0.5 NM (0.93 km) from a built-up area;

- (6) Operate at a maximum distance of 0.5 NM (0.93 km) from the pilot;

- (7) Operations over or within open-air assemblies of persons (see footnote 8) would not be allowed;

- (8) Operate below 300 feet (91.44 m) or 100 feet (30.48 m) above a building or structure with conditions;

- (9) Operate at less than 87 knots (100 mph); and

- (10) Night operations would not be allowed.

Small UA (complex operations)

Operating a heavier UA near populated areas may pose a greater probability and severity of an incident or accident involving people or property. Operations within 0.5 NM (0.93 km) of a built-up area, near an aerodrome or in controlled airspace would necessarily need preparations and involve more than buying a UAS and reading the operating manual. If a person would want to operate a UA that weighs more than 1 kg but not more than 25 kg in this type of environment, it is proposed that they adhere to the following three unique requirements:

- (1) Have a UAS that is in compliance with a standard published by a standards organization accredited by a national or international standards accrediting body; (see footnote 9) have available the statement from the manufacturer that the UAS meets the standard; and do not modify the UAS. Transport Canada would alleviate the requirement for a pilot/operator to have a UAS that meets the design standards for operation in a complex operating area if that pilot/operator has bought a UAS prior to the coming-into-force date of the new regulations;

- (2) Register the UAS with Transport Canada and ensure that the certificate of registration is readily available by the pilot-in-command; and

- (3) Obtain a pilot permit that would be valid for five years. The pilot permit application to Transport Canada would include, for example, the following:

- • An attestation of piloting skills by another UA pilot, and

- • The successful completion of a comprehensive knowledge exam.

The following requirements and limits would also apply:

- (1) Pass a comprehensive written knowledge test (part of the pilot permit requirement above);

- (2) Be at least 16 years of age;

- (3) Request and receive authorization for flight in airspace which is a control zone for an aerodrome from the appropriate air traffic control unit;

- (4) Operate at least 100 feet (30.48 m) from a person. A distance of less than 100 feet would be possible for operations if conditions such as a maximum allowed speed of 10 knots (11.5 mph) and a minimum altitude of 100 feet are respected;

- (5) Operate at a maximum distance of 0.5 NM (0.93 km) from the pilot;

- (6) Operate over or within open-air assemblies of persons if operated at an altitude of greater than 300 feet, but less than 400 feet, and from which, in the event of an emergency necessitating an immediate landing, it would be possible to land the aircraft without creating a hazard to persons or property on the surface;

- (7) Operate at a maximum of 400 feet (121.92 m) or 100 feet above a building or structure with conditions; and

- (8) Night operations would be allowed with conditions.

Transport Canada has conducted a specific analysis in relation to operations of UAs near or within built-up areas, considering risks to people and the proximity and type of UA involved. The following is a summary of minimum lateral distances that pilots/operators of UAS would have to respect depending on their operating category.

| Type of UAS Unit | Pilot Has Authorization for | Location | Distance From | Distance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very small | Rural or built-up area | a person | 100 feet (see footnote a1) | |

| Very small | Near an aerodrome or heliport | an aerodrome or heliport | 3 NM or 1 NM respectively | |

| Small | Limited operations | Near a built-up area | a built-up area | 0.5 NM |

| Small | Limited operations | Rural area | a person | 250 feet (see footnote a2) |

| Small | Limited operations | Near an aerodrome | an aerodrome | 3 NM (see footnote b1) or control zone |

| Small | Complex operations | Within a built-up area | a person | 100 feet (see footnote a3) |

NM is nautical mile (1 NM = 6076.12 feet = 1.852 km)

Manufacturer

The manufacturer would have to design a UAS to be used in complex operations to minimum standards, (see footnote 10) send a declaration of compliance to Transport Canada and provide a statement of conformity to any pilot or operator who requires one.

Special flight operations — UAS

Any UAS operated under the following categories would retain the current SFOC process for authorizing operations on a case-by-case basis:

- Beyond visual line-of-sight (BVLOS);

- UA that weighs more than 25 kg;

- UA flown for air races, air demonstrations, or air shows; and

- Any other operation where an operator cannot comply with all of the proposed regulatory provisions for their particular UA weight category or location of operation.

Benefits and costs

The net costs of the proposed amendment are estimated as $61.48 million PV or $8.75 million annualized. The benefits and costs are estimated as the expected increases or decreases in impacts compared to the baseline of current regulatory compliance. The current baseline includes non-recreational UAS operators that are operating per SFOC; non-recreational UAS operators that are operating without having an SFOC, but who should have applied; and recreational UAS pilots that are operating in accordance with the Interim Order.

Benefits

The public security benefits of further regulating the UAS industry are difficult to monetize, since much of it pertains to uncertain forecasts of this emerging industry. However, based on past incident data, Transport Canada foresees the following qualitative public security benefits of the proposed amendment:

- It is assumed that the cost savings from preventing any manned aviation accident would outweigh the net costs of the proposed Regulations.

- Aircraft marking and registration could assist Transport Canada and the police in regulatory enforcement investigations or the Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) in safety investigations into aircraft incidents or accidents involving manned and unmanned aircraft. It could also assist civil authorities to take action for any possible criminal related activities involving UASs.

- Entering small UAs eligible to operate in complex environments into the Canadian Civil Aircraft Register database could provide Transport Canada with current and historical statistical information that would provide perspective in managing accident and incident rates and future regulatory amendments.

- A UAS that has been designed, manufactured and maintained to a minimum standard may reduce the risk of incidents, such as fly-aways, or accidents and the severity of the consequence of an incident or accident.

- Mandating operators who are not already compliant with an SFOC, but should be, to put in place procedures such as a site survey or emergency procedures may reduce the risk of incident or accident.

Qualitative economic benefits for all sectors of the UAS industry, including manufacturers, operators, training units and retail establishments, could include the following:

- The fact that the UAS pilots should have knowledge testing encourages the growth of competent and skilled third party approved exam invigilators (AEI) as well as a growth in education and training providers.

- By mandating minimum safe operating limits and procedures, all of the industry sectors would benefit from a public confidence perspective that would in turn encourage continued growth in businesses.

- The fact that the UAS should be designed, manufactured and maintained to a minimum standard encourages the growth of a specialized sector in Canada comprised of competent and skilled workers.

The total estimated monetized benefits are primarily due to the reduced burden of preparing for SFOCs compliance and administration for each of the businesses or institutional UAS operator (i.e. police or university). It is assumed that all of the businesses are small businesses. The benefit estimate is approximately $111 million PV over 10 years with a 7% discount rate, which equates to an annualized value of approximately $16 million. The estimate is calculated using the historical number of SFOCs issued between the years 2012 and 2016 and then using the average growth rate of 2.0% to obtain 8 703 SFOCs issued in 2017. Year one of the analysis is 2018 and the number of SFOCs assumed to be issued in that year is 11 000. The forecast of SFOCs issued over 10 years, if the proposed Regulations are not made, follows a trend similar to a Japanese study (see footnote 11) regarding large unmanned helicopters for agriculture use. While the study is only for one industry sector, Transport Canada is of the view that this trend for forecasting may be more realistic than comparing it to the trend of consumer smart phones for instance, since SFOC operators are non-recreational.

The time for a business to prepare the SFOC request is estimated at $37 per hour for 2 days or 16 hours. For complex operators, the estimate includes the preparation related to air traffic service provider coordination, i.e. obtaining a call sign (see footnote 12) since this would be replaced by the registration process. The UAS operator would no longer need to establish, in coordination with each applicable local air traffic service provider, a call sign to be used during the particular operation in order to facilitate communication and avoid duplication of call signs. The total cost savings for businesses are estimated to be $82.34 million PV or $11.72 million annualized.

The total estimated monetized benefits for the Government are due to the reduced burden of Transport Canada of issuing SFOCs. The benefit estimate is $28.63 million PV, which equates to an annualized value of approximately $4.08 million. Based on a survey conducted by Transport Canada, the Department's inspectors spent on average 3.1 hours to process a simple SFOC application and 4.8 hours to process a complex SFOC application at $94 per hour. A simple application is an application that was developed for recognized UAS operators with a previous history of SFOC requests.

| Stakeholder | Benefit | Cost Savings (Present Value over 10 Years with a 7% Discount Rate) |

|---|---|---|

| Business or institutional operator | Reduced administrative burden of applying for SFOCs and establishing a call sign | $82.34 million |

| Transport Canada | Reduced administrative burden of processing SFOCs | $28.63 million |

Costs

The cost estimates can be explained for each of the three stakeholder groups: recreational UAS pilots, industry businesses/institutions, and government. As stated in the description, the proposed Regulations intentionally do not distinguish between recreational and non-recreational operations. However, for the purposes of an individual identifying with one or the other, the cost estimates are categorized as such for one year only for illustrative purposes.

Recreational UAS pilots

It is assumed that the majority of the UA units that weigh more than 250 g but less than 1 kg (referred to as very small UAs) would be operated recreationally. The recreational UAS pilot would have to take a basic written knowledge test for a minimum of $35 and mark their UA with contact information at no cost. The liability insurance industry for recreational UAS operators is not yet mature. However, it may be assumed that the cost of $100,000 of liability insurance for a recreational UAS operator is estimated as twice the group insurance premium for a modellers association. Liability insurance could amount to an estimated $15 per year. Therefore, the total cost for a pilot with a very small UAS is estimated to be $50 for the first year.

Recreational pilots operating a UA unit that weighs more than 1 kg but not more than 25 kg (referred to as small UA) in a rural area (limited operation) would also carry the total estimated cost of $50 for licensing and liability insurance per year.

For recreational pilots operating a UA unit that weighs more than 1 kg but not more than 25 kg (small UA) in a built-up area (complex operation), the costs would be as follows:

- $15 or more per year for liability insurance of at least $100,000;

- $110 upfront cost of applying for registration marks for every new UAS acquired;

- $35 upfront cost for invigilation of a comprehensive knowledge exam in order to obtain a pilot permit;

- $35 upfront cost for a pilot permit.

The total cost estimate for a recreational pilot operating a UA unit that weighs more than 1 kg but less than 25 kg in a built-up area is $195 in the first year and $15 or more thereafter.

| UA Weight | Area of Operation | Cost in year 1 (2018) (see footnote 13) |

|---|---|---|

| More than 250 g but not more than 1 kg (very small) | Rural or built-up area | $50 |

| More than 1 kg but not more than 25 kg (small) | Rural area (limited operation) | $50 |

| More than 1 kg but not more than 25 kg (small) | Built-up area (complex operation) | $195 |

Industry businesses and institutional operators (non-recreational)

The majority of UAS businesses in Canada have fewer than 100 employees. The exception, for example, would be energy companies that would operate UASs to inspect their oil lines or electricity lines. For the purposes of this analysis, all of the UAS operators are considered small businesses.

The cost estimates for businesses with pilots that would strictly operate UAs that weigh between 250 g and 1 kg (very small) would be similar to that of a recreational pilot, but Transport Canada also includes the time spent for administrative burden and compliance burden, such as time to write a test, in the estimate. It is assumed that the businesses would already have liability insurance. The cost estimate is as follows:

- $35 upfront cost for invigilation of a basic knowledge exam in order to obtain a pilot permit; and

- Written exam time — 1 hour multiplied by the Canadian salary average = $25.20/hour.

The total first-year cost estimate for a business with one pilot operating a UAS that weighs between 250 g and 1 kg would be $60.

The cost estimates for businesses with pilots that would operate UASs that weigh between 1 kg and 25 kg (small) in a rural area would be similar to that of those operating the less heavy UA units. The total first-year cost estimate for a business with one pilot operating a small UA in a rural area would be $60.

Most of the businesses that have been applying for SFOCs operate small UA units or have a combination of very small or small UA units, depending on the business sector applicability. Since cost estimates are calculated as those being related to proposed new requirements and not that of current regulation or voluntarily action, many of the requirements related to operating procedures are not included in this cost analysis. The operators that are already operating pursuant to an SFOC have operating procedures in place. It is assumed that the businesses would also already have liability insurance.

The cost estimates for businesses with pilots that would operate small UA in built-up areas for the new requirements that are not already an SFOC requirement are as follows:

- $110 upfront cost of applying for registration marks for every new UAS acquired;

- Aircraft registration application = 30 minutes × Canadian salary average = 0.5 × 25.20 = $12.60;

- $35 upfront cost for invigilation of a comprehensive knowledge exam in order to obtain a pilot permit;

- Time to take the exam (study not included) = 2 hours × Canadian salary average = 2 × 25.20 = $50.40;

- Pilot permit application = 30 minutes × Canadian salary average = 0.5 × 25.20 = $12.60; and

- $35 upfront cost for a pilot permit.

The total cost estimate for businesses with pilots operating small UA in built-up areas in the first year would be $256.

Based on the total estimate of small UA units in Canada in 2016 in populated areas compared to the volume of SFOC applications that Transport Canada has received in 2016, Transport Canada assumes that up to two thirds of businesses that operate small UA are currently non-compliant and should have applied for an SFOC. It is also assumed that they do not carry liability insurance. Transport Canada inspectors have noted that a few operators that currently have SFOCs were found to have no liability insurance.

The liability insurance market for a business is more established than for the recreational market. For businesses, typical annual liability costs range between $500 and $1,000, as it is assumed they are operating their UAS more frequently than do recreational pilots. The lower estimate is used for the cost estimate.

The cost estimates for businesses with pilots that would operate small UAs in built-up areas and are not already compliant with SFOC conditions are as follows:

- $500 per year for liability insurance;

- $110 upfront cost of applying for registration marks for every new UAS acquired;

- Aircraft registration application = 30 minutes × Canadian salary average = 0.5 × 25.20 = $12.60;

- $35 upfront cost for invigilation of a comprehensive knowledge exam in order to obtain a pilot permit;

- Time to take the exam (study not included) = 2 hours × Canadian salary average = 2 × 25.20 = $50.40;

- Pilot permit application = 30 minutes × Canadian salary average = 0.5 × 25.20 = $12.60;

- $35 upfront cost for a pilot permit;

- Practical training self-taught summary = 2 hours × Canadian salary average = 2 × 25.20 = $50.40; and

- Maintain records of flight operations: the administrative burden of keeping a flight log up to date. It is assumed that each log entry takes one minute multiplied by an average salary, and an average of 100 flights is undertaken per year = 0.0167 × $25.20 × 100 = $42.00.

The total cost in the first year for this population of businesses and institutional UAS operators is $848 per operator.

There is a small number of manufacturers (12 businesses) that build UAS in Canada. Transport Canada assumes that the cost of designing and showing compliance to an industry standard is already done for those whose target market is operation in built-up areas, for movie production, as an example. In addition, future designs for that market already meet or exceed the existing industry design standard. It is estimated that for the 12 manufacturers to complete a required compliance matrix, explaining how all requirements per the industry standard have been met, which is typically done by an engineer, and to produce statement of conformity copies, it would take 5 days or 37.5 hours as an upfront cost = $1,067 in the first year. For any new models developed in subsequent years, the costs would be rolled into typical development cost.

| Stakeholder | UA Weight | Area of Operation | Cost in Year 1 (2018) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Owner/Pilot | More than 250 g but not more than 1 kg | Rural or built-up (limited or complex operation) | $60 |

| Owner/Pilot | More than 1 kg but not more than 25 kg | Rural (limited operation) | $60 |

| Owner/Pilot currently compliant with an SFOC | More than 1 kg but not more than 25 kg | Built-up (complex operation) | $256 |

| Owner/Pilot currently not compliant with an SFOC | More than 1 kg but not more than 25 kg | Built-up (complex operation) | $848 |

| Manufacturer | More than 1 kg but not more than 25 kg | $1,067 |

Total cost estimates taking total Canadian UAS units and businesses/institutions into account.

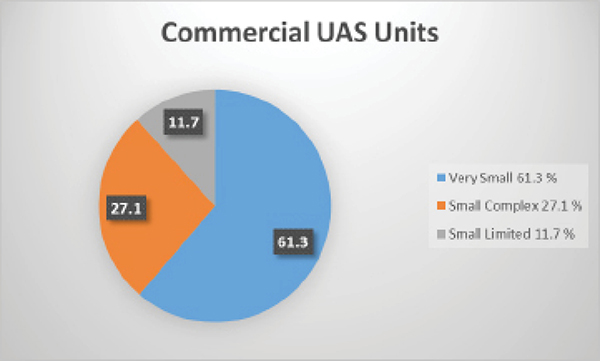

The number of UASs in Canada has been estimated at approximately 337 468 units at the end of 2017. The total UAS population in Canada is calculated as 12% of the U.S. estimate of 2 812 237 UAS units in use at the end of 2017. The underlying assumption is that the ratio between the U.S. manned aircraft pilots and Canadian manned aircraft pilots is equal to the ratio between the U.S. UAV units and Canadian UAV units. The ratio of 12% stems from the assumption that there are more pilots per capita in Canada than in the United States, where the simple population ratio would be closer to 11%. It is assumed that the UAS industry will continue to grow rapidly and then start to level off. The growth rate of SFOCs, although non-recreational only, is a good indication of what may be expected as a continued growth rate in the next few years. The number of SFOC applications has actually had a growth rate of 2.0%. Therefore, the total number of UAS units estimated for the cost analysis is 575 600 at the end of 2018.

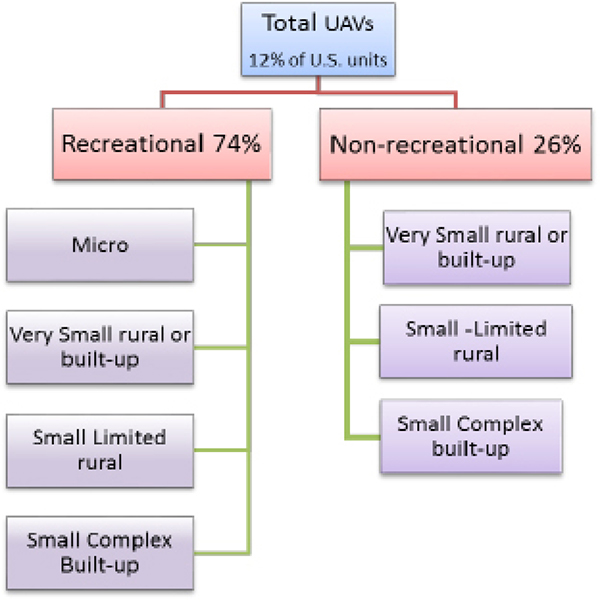

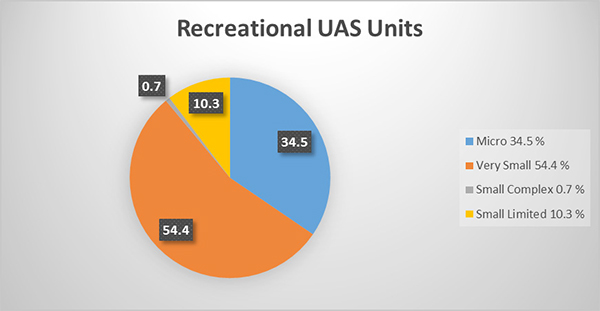

The total UAS units are thus broken down into recreational (see footnote 14) and non-recreational (see footnote 15) percentages of 74% and 26%, respectively, based on the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) aerospace forecast 2016–2026. The assumed breakdown of UAS unit categories is as illustrated in the following chart. Should there be more of a proportion of small UA being operated in rural areas, the cost estimate would prove to be conservative since there would be more requirements for operation of small UA in built-up areas.

The total number of UAS units estimated to be operated in Canada by the end of 2018 is summarized in the following chart. It is to be noted that the model unit numbers and BVLOS UA unit numbers are part of the total assumption but not further included in the analysis since they would be part of different regulatory requirements.

| Model | Micro | Very Small | Small Limited | Small Complex | Large/BVLOS | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada units (end 2018) | 42 700 | 140 000 | 298 000 | 56 700 | 37 200 | 195 | 575 600 |

| Percentage breakdown | 7% | 24% | 52% | 10% | 6% | <1% | 100% |

The actual number of small UA units that are flown recreationally versus non-recreationally is unknown. Basic assumptions have been made to be able to differentiate the costs to determine the total number of businesses so as to estimate the administrative burden as shown in the “‘One-for-One' Rule” section of this Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement (RIAS).

Since the requirements in the proposed amendment hinge on the type of UAS and the type of UAS operation conducted, the differentiation between the UAS operated recreationally and non-recreationally is based on the following gross assumptions:

- All micro UA are operated recreationally; micro UA units may be used non-recreationally as technology advances;

- Most of the very small UA would be operated recreationally; and

- Most of the small UA would be operated non-recreationally.

For the purposes of the cost analysis, the following table and diagrams show the assumed UAS unit distribution. The micro UA units are shown for illustrative purposes since they contribute to a large part of the recreational market.

| UAS Unit | Micro | Very Small | Small (Limited) | Small (Complex) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operated recreationally | 140 000 | 220 520 | 41 958 | 2 976 |

| Operated non-recreationally | 0 | 77 480 | 14 742 | 34 224 |

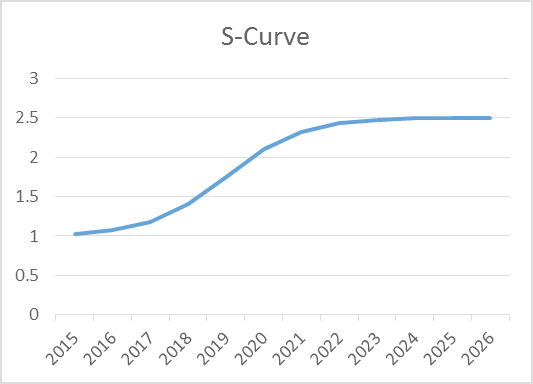

The Treasury Board Secretariat of Canada requires that a cost-benefit analysis be made over a 10-year period as a minimum. The total cost estimate excluding the government cost estimate is calculated by using all of the costs listed for the individual stakeholders multiplied by the total population of each of the units estimated in the very small, small limited and small complex categories. The cost estimate to manufacturers is calculated separately. The growth of the industry that is assumed over the next 10 years follows an S-curve with a 1.5 times saturation point. A 1.5 saturation was chosen due to an assumed balance of industry potential and safety and insurance cautions from regulators, pilots and the public. The growth of UAS units that would be operated in Canada would level off at 2.5 times the value assumed in year one (2018). Over 10 years, 100% compliance is assumed to be achieved through outreach, surveillance and enforcement, as the operators who may be currently non-compliant would decrease inversely to the S-Curve.

Government

Government cost estimates are associated with the personnel to be put in place to support the program as well as some information technology (IT) platform capital costs.

Development of training curriculum

It is estimated to take 18 months for two Transport Canada full-time employees (FTE) to develop the formal knowledge material for the exam for pilots operating UA in the small complex category. The FTEs would develop 4 different exams that would have about 100 questions each. The exam model would be similar to the recreational boaters' exam model. Exams would be refreshed every three years and the exam invigilation program would have to be maintained annually with 1.5 FTE. Transport Canada has an existing system that allows Authorized Exam Invigilators (AEI) to invigilate exams. Small limited and very small UA basic knowledge test will be a subset of the small complex UA knowledge requirements and will take less effort to develop and put online. Translation costs were not added to the estimate.

Administration

The administrative portion of the government cost estimate would be related in part to aircraft identification, marking and registration. The Minister would enter all small UA operating in the small complex operating areas into the Canadian Civil Aircraft Register database. Transport Canada would allocate a unique series of registration marks, starting with a specific letter (C-Xabc). This would provide an easy manner to differentiate between manned and unmanned aircraft and would support search and rescue and air traffic control concerns and practices. Three new FTEs would be required to manage the requests and issue the registration certificates. One new FTE (Information Technologist) and a support person would be required to modify the registration database to accommodate the UAS numbers.

Personnel licensing also contributes to the administration part of the program. One new FTE (Inspector) would be required to process and produce the permit, which is a Canadian Aviation Document (CAD). An estimated 11 000 to 33 800 pilot permits may be requested by the end of 2018. The high range was chosen for conservative cost-benefit calculations. A program manager would also help the Inspector manage the CAD activities in general.

Surveillance costs

There are currently 16 inspectors who are processing SFOCs in Canada. During the first two years following the coming-into-force date of the regulations, 14 of those inspectors would be transferred gradually to the existing manned aircraft surveillance program and 2 would be retained to continue to process SFOCs. It is estimated that over the remaining eight years of the period covered by the cost analysis, 12 new FTEs (inspectors) would be needed for the UAS surveillance program.

By calculating employee salaries over 10 years with a discount rate of 7%, the total cost estimate for Transport Canada would be $18.10 million PV or $2.58 million annualized.

Cost-benefit statement (see footnote a)

| Base Year: 2018 | 2019 to 2026 | Final Year: 2027 | Total (PV) (see footnote b) | Annualized Average | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Quantified impacts (in CAN$ millions, 2012 price level / constant dollars) | ||||||

| Benefits | All business and institutional operators | 7.54 | 13.04 | 13.42 | 82.34 | 11.72 |

| Benefits | Government | 2.62 | 4.53 | 4.67 | 28.63 | 4.08 |

| Total benefits | 10.16 | 17.58 | 18.09 | 110.97 | 15.80 | |

| Costs | Recreational UAS pilots | 10.0 | 8.55 | 2.96 | 44.43 | 6.33 |

| Costs | All business and institutional operators | 23.61 | 19.42 | 9.03 | 109.92 | 15.65 |

| Costs | Government | 3.38 | 2.52 | 2.39 | 18.10 | 2.58 |

| Total costs | 36.99 | 30.50 | 14.38 | 172.45 | 24.55 | |

| Net costs | -26.84 | -12.92 | 3.70 | -61.48 | -8.75 | |

B. Quantified impacts in non-$ N/A C. Qualitative impacts |

||||||

Industry, Government and general public: Cost savings of an averted accident or incident Industry: Ability to plan contracts with more certainty |

||||||

“One-for-One” Rule

The “One-for-One” Rule applies as an OUT since the assumption is that the proposed regulatory amendment decreases the administrative burden on business due to it replacing the existing SFOC process for a large population of UAS non-recreational operators.

The proposed Regulations do, however, add some administrative burden. The following would be considered administrative burden and was estimated for existing pilots and operators assumed to be operating in year one of the regulations and then for the assumed growth of pilots and operators assumed (S-curve) over the 10-year analysis:

- Aircraft registration application — small complex operations (30 minutes per UAS, assumed a new UAS every two years);

- Pilot permit application — small complex operations (30 minutes);

- Practical training self-taught summary — very small and small limited operations (2 hours); and

- Maintain records of flight operations — small limited and small complex operations (5 minutes multiplied by 100 flights per year average).

For the purposes of calculating the administrative burden, the number of operators has to be assumed. The number of operators is estimated as the number of SFOCs forecast in 2018 times 0.62, since many of the UAS operators have applied for and have been issued SFOCs more than once a year. Based on this ratio, it is estimated that there would be 21 500 companies in 2018. This estimate takes into account that many of the operators that may be out of compliance (i.e. operating without an SFOC) would become compliant with the proposed Regulations.

The administrative burden for the manufacturers was also taken into account to produce the compliance matrix as five days of a manager's time for each of the 12 estimated manufacturers in Canada. The portion of total administrative burden pertaining to the manufacturers amounts to $19,500 PV over 10 years, or $2,800 annually.

The annualized net administrative cost savings estimate is $5.43 million in 2018 prices.

| Estimate | Assumptions | PV $ million (2018) | Annualized $ million (2018) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost savings due to reduction of SFOCs | Calculated using number of SFOCs expected if the proposed Regulations would not be put in place. | 81.49 | 11.60 |

| Cost of aircraft registration | Registration time spent (30 minutes) once every two years using estimated number of UASs to be operated non-recreationally in the small complex operating environment over 10 years. Increasing compliance of operators taken into account. (see footnote 1*) | -5.11 | -0.73 |

| Cost of pilot permit application | Upfront cost (30 minutes) using estimated number of non-recreational UAS pilots in the small complex operating environment. (see footnote 2*) | -0.43 | -0.06 |

| Maintain records of flight operations — small limited and small complex operations | Recurrent cost based on the number of pilots operating non-recreational small UA. (see footnote 3*) | -11.48 | -1.63 |

| OUT | 64.48 | 9.18 | |

According to the Red Tape Reduction Regulations for calculating administrative burden, the net savings or costs are calculated and reported in 2012 dollars. The net cost savings related to administrative burden in 2012 dollars is estimated as follows:

| Annualized administrative net savings (constant 2012 $) |

$5,431,672 |

|---|---|

| Annualized administrative net savings per business (constant 2012 $) | $252 |

The feedback from business owners related to the administrative burden of applying for SFOCs was related to the service standard of a reply rather than the time it took to fill out the application. No business owner has expressed concern regarding the proposed added administrative burden.

Small business lens

The small business lens does apply because costs to small businesses are estimated to increase overall. However, much of this increase is due to the assumption that two-thirds of the pilots and operators operating in a built-up area are doing so without having applied for an SFOC and are currently non-compliant. It is assumed that the average small business will have an increased annual cost of $287.

The total quantified increase in administrative and compliance costs to small businesses is shown in the cost-benefit statement. The net cost per business is not considered overly burdensome, given that the costs would be mostly up front and not recurring unless the business decides to buy new UASs regularly. In that case, the registration of UA weighing between 1 kg and 25 kg operated in built-up areas would be recurrent.

Small businesses were consulted on the Notice of Proposed Amendment (NPA) when Transport Canada was developing this regulatory proposal. Since many of these small businesses are not part of the traditional manned aviation community, social media was used to engage UAS stakeholders, including small businesses.

Transport Canada considered ways to reduce compliance costs for small businesses such as to extend the compliance time from zero months to six months. Allowing six more months for small businesses to comply would yield some cost savings. The following table compares the total costs between the initial option (zero time to comply) and the flexible option (six months to comply).

| Flexible Option | Initial Option | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short description | All small businesses would have six months to comply | All small businesses would have to comply by the coming-into-force date (time of Canada Gazette, Part II, publication) | ||

| Number of small businesses impacted | 21 500 | 21 500 | ||

| Annualized Average ($ 2012) |

Present Value ($ 2012) |

Annualized Average ($ 2012) |

Present Value ($ 2012) |

|

| Compliance costs | $4,897,002 | $34,394,489 | $5,065,498 | $35,577,937 |

| Administrative costs | $1,272,857 | $10,067,910 | $1,451,847 | $10,197,163 |

| Total costs for all small businesses | $6,169,859 | $44,462,400 | $6,517,344 | $45,775,099 |

| Average cost per small business | $287 | $2,066 | $303 | $2,127 |

| Risk considerations | There are no foreseeable risks related to the flexible option. | Service standards may delay compliance for some businesses. | ||

In comparison to the Initial Option, the Flexible Option recommended by Transport Canada would reduce the annualized average cost by $347,485 for all businesses, or $16 per business per year.

Transport Canada will take further measures to promote small business compliance by

- Informing industry and conducting compliance promotion activities;

- Holding outreach sessions with new stakeholders, including small businesses; and

- Planning additional outreach sessions in 2018 and 2019, once the proposed requirements are finalized.

In addition, Transport Canada will

- Ensure all forms and processes and web pages comply with the Government of Canada's common look and feel;

- Prepopulate forms with information or data it already has available, to reduce the time and money businesses would have to spend to complete them; and

- Collect data electronically and use electronic validation and confirmation of receipt of notice where appropriate.

For small businesses in remote areas and/or those without access to high-speed (broadband) Internet, prospective UAS operators may

- Request documents be sent to them by mail;

- Call Transport Canada for any assistance they require; or

- Provide information via fax, and Transport Canada will enter the information into its database, if needed.

Consultation

The Notice of Proposed Amendment (NPA), Unmanned Air Vehicles, was published on May 28, 2015, for a 92-day consultation period ending on August 28, 2015. It was shared via email with the 570 traditional aviation stakeholders, members of the Canadian Aviation Regulation Advisory Council (CARAC). In addition, recognizing that unmanned air vehicle stakeholders are different from traditional aviation stakeholders, the NPA was also emailed to 160 non-CARAC members across Canada composed of UAS companies, associations (e.g. Canadian Real Estate Association), and other stakeholders such as federal or provincial governments that may have expressed an interest in UAS to Transport Canada. Given the high media attention surrounding UAS, exceptionally Transport Canada's Communications and Marketing team promoted the NPA through a news release and social media postings, as NPAs are normally not shared using social media.

In addition to the email consultations on the NPA, five regional round tables and a national teleconference were organized across Canada in July 2015 in order to share with stakeholders the proposed changes. Participants in these round tables represented a mix of UAV operators, law enforcement, and provincial and federal partners.

At the end of the consultation period, Transport Canada had received over 100 submissions on the NPA. Of these

- 36 (34%) were sent from businesses that offer activities related to UAVs (e.g. Amazon, DJI and TDV Solutions);

- 22 (21%) came from various associations (e.g. Unmanned Systems Canada [USC], Model Aeronautics Association of Canada [MAAC], Canadian Owners and Pilots Associations [COPA], National Airlines Council of Canada [NATA], Air Line Pilots Association, International [ALPA], Ultralight Pilots Association of Canada [UPAC] and the Retail Council of Canada);

- 21 (20%) were sent from private citizens;

- 10 (10%) came from federal and provincial governments and agencies, including NAV CANADA, Office of the Privacy Commissioner, RCMP, Government of Manitoba, Government of NWT, Sûreté du Québec, Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre and Ministry of Transportation of B.C.; and

- the remaining comments came from the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration, Kelowna Airport, two insurance companies, one law firm, one media company (Bell Media), and two universities.

Of the 100 plus comments, the following are chosen as highlights for the purpose of impact analysis and will be discussed in the “Rationale” section of this RIAS:

- Pilot associations and air operator associations support a measured approach to developing regulations and Transport Canada's ongoing focus of keeping UA out of airspace surrounding airports where non-recreational flights operate.

- The Retail Council of Canada suggested a weight threshold of 3 kg for UA and simple registration, but supports proposed regulations in line with U.S. regulations.

- The Canadian Real Estate Association welcomes the proposed amendments to modernize the regulations, but raised concerns with the current delays with the SFOC process.

- NAV CANADA made suggestions on all elements of the NPA, but also raised concerns that while Transport Canada will reduce the resources required for SFOC application and processing, NAV CANADA will be required to manage UA access to controlled airspace.

- RCMP (operations) suggested testing to determine the appropriate lower threshold for the very small UA category since they felt that the 2 kg upper limit might be too high; an operator certificate would add to the administrative responsibilities; in an attempt to define when organizational requirements would be required, a company would need to have more than 3 pilots; Transport Canada should be involved in the approval of training units; professional operators should be able to operate at an aerodrome with appropriate ATC coordination; agreed to regulating all the limited operations category and the introduction of a design standard.

In addition, there was some disagreement that a model aircraft cannot be used recreationally for photography. The proposed amendment differs from the NPA in that camera and video equipment is allowed recreationally noting that it adds to the determination of the weight of the UAS. If a UAS is used recreationally in a rural area, the operator would need to have insurance, identify the UAS, as well as pass a basic UAS knowledge test.

Since the NPA consultations, further safety analysis has led Transport Canada to reduce the upper limit of the very small UA category from 2 kg to 1 kg. The safety analysis is referred to in the “Rationale” section of this RIAS, where the severity of an incident or accident was considered given the fact that the very small UA operating category would have fewer mitigating measures in place, such as a pilot permit and design standard.

The proposed amendment differs from what was consulted on in a few areas that would alleviate requirements. The requirement to submit a category 4 self-declared medical form was removed since there is no data that would support this requirement and its removal would remove administrative burden. Minimum lateral distances from buildings, structures and animals have been removed since they are all protected by other laws that are not part of Transport Canada's jurisdiction, such as privacy laws and animal protection laws.

The proposed amendment differs from the NPA in two other areas, which will be further explored for subsequent regulatory proposals.

- (1) It was originally thought that aero-modellers with a UA above 1 kg, for instance, would not have to pass the Transport Canada knowledge test, identify their UA and have their own insurance. The NPA describes this segment of the UAS community as responsible for maintaining an excellent safety record by establishing safety codes and ensuring that members adhere to those safety codes. The proposed amendment does not preclude a person from joining an aero-modeller association where one could benefit from the group liability insurance provided by the association. The consideration that associations other than MAAC would want to benefit from the privileges of a mentoring type community led Transport Canada to delay regulating these types of associations until criteria could be developed that would provide equivalent safety within these emerging associations. Until those criteria have been identified and further regulatory changes have been introduced, an exemption to the proposed Regulations applying to persons who are members of MAAC in good standing will be issued by Transport Canada. The Aeronautics Act authorizes the Minister of Transport to exempt any person from the application of any regulation made under this Act, provided the exemption is in the public interest and is not likely to adversely affect aviation safety. Since MAAC members have demonstrated over time a safe operating record, this exemption is expected to be made available when the proposed Regulations are in force.

- (2) It was proposed that operators with larger complex organizations having a management structure and many pilots to manage would have to meet specific requirements to obtain an operator certificate. An operator certificate would have required a company to not only have procedures in place but also documentation pertaining to staff training, staff qualifications, UAS operating manuals and maintenance manuals. Transport Canada decided to defer the requirement to apply for and maintain an Operating Certificate. Basic requirements contained in the proposed Regulations pertain to processes and procedures to provide safe operation but do not require manuals to be in place, for instance. The regulations do not preclude an operator from adhering to the current guidance concerning having a management structure and having pilot and operating manuals in place.

In summary, with the exception of one submission from a video production company owner that was against the proposed Regulations altogether, there was strong support to introduce new regulatory requirements for UAS. The anticipated position of stakeholders is to support the proposed amendment.

Regulatory cooperation

Since 2015, Transport Canada and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) have collaborated in the area of unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) under the Regulatory Cooperation Council (RCC). The collaboration has focused on information exchange pertaining to the respective proposals to introduce new regulations for small UA operated within visual line-of-sight.

Canada is a member of the Joint Authorities for Rulemaking on Unmanned Systems (JARUS). (see footnote 16) JARUS is a group of experts gathering regulatory expertise from around the world. JARUS is open on a voluntary basis to all civil aviation authorities and industry stakeholders to make recommendations on operational, technical and certification requirements. This is a joint effort to share knowledge and provide harmonized requirements that helps members establish their own regulatory frameworks.

The FAA published its Final Rule, Part 107, Operation and Certification of Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems, in June 2016 to permit lower risk non-recreational UAS operations. It came into effect on August 29, 2016. Before that time, non-recreational UAS were operated under an exemption from airworthiness requirements, issued on a case-by-case basis. The proposed amendment aligns with the FAA's general scope, intent and risk-based approach. The FAA has opted for a phased approach to regulating UAS and so far has prescriptive rules governing rural operations only (Part 107 in Annex B). The FAA will introduce regulations for the operations of UA over people and buildings in the near future. For now, the FAA has a waiver system that is similar to Transport Canada's SFOC process.

The FAA has supported work on the same industry design standard that Canada would use. Canada did not participate in an industry working group that developed a relevant UAS design standard, but acknowledges that it is internationally recognized. (see footnote 17)

When both the FAA and Transport Canada complete their respective phased approach to regulating UAS, the remaining differences may only pertain to registration and operating altitude. The FAA requires all pilots and operators to register any UA over 250 g, while Transport Canada proposes that only UA above 1 kg in small complex operations be registered. The FAA allows for operations of UA that weigh less than 25 kg in rural areas to a maximum altitude of 400 feet, while the limit would be 300 feet in Canada with conditions. The United States chose 400 feet as a maximum altitude limit for UA since manned aviation in the United States has a lower limit of 500 feet, thus providing a buffer of 100 feet between UA and manned aircraft. An altitude limit of 300 feet is proposed for UA in Canada because the manned aviation lower limit of 500 feet does not exist in rural areas. In addition, the limit would correspond with the fact that any obstacles over 300 feet must be marked and have appropriate lighting in Canada.

Canada has not determined reciprocal foreign operator privileges with the United States. Similarly, the FAA 107 rule excludes foreign operators. Foreign operators are eligible to apply for an SFOC providing they are legally entitled to conduct the same operation in their own country. They need to provide evidence of such approvals when they apply for an SFOC.

All European member states are at different stages in the implementation of their UAS rules, but are subject to the requirements and guidance of the European Union and the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). In March 2015, the European Commission member states established four principles (see footnote 18) (the Riga Declaration) to guide the integration of UAS into European airspace and facilitate the growth of the UAS economy. In December 2015, EASA released its technical opinion on UAS, and identified three categories of operation (see footnote 19) that are commensurate to risks involved, to inform the development of state rules, guidance material, and safety promotional information.

Canada is a member of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and adopts ICAO standards into the CARs. ICAO has no standards for VLOS operations per se. ICAO does have guidance (see footnote 20) on the type of information that operators are requested to submit to the aviation authority in the country in which they wish to operate. Transport Canada's current regime and the issuance of an SFOC satisfies this intent. ICAO is focused more on larger UA that will be certified like aircraft and for which future regulations should be introduced in Canada.

Rationale

There has been a dramatic increase not only in the number of people buying UAs, but also in the number of users flying them dangerously close to manned aircraft and people on the ground.

The likelihood of further incidents was further analyzed by Transport Canada and based on Air Occurrence Report (AOR) incidents collected since January 2014. In 2014, there were 41 incidents of non-compliance reported. In 2015, the number of reported incidents more than doubled to 86, and a total of 148 incidents near aerodromes were reported in 2016. A few of the reports include flights near people or vehicles, but the existing AOR system tends to rely on pilot and air traffic controller reports, therefore incidents near people, vehicles, or property on the ground tend to be underrepresented in the data. The reports show a number of important trends that speak to the potential hazards for other aircraft such as the following:

- The incidents represent a mixture of flights by recreational users (model aircraft) and non-compliant UAS operators (non-recreational). None of the incidents so far were traced to individuals flying under the auspices of a recognized modelling association and only a small percentage of incidents were traced to UASs operated by persons who had been issued special flight operations certificates (SFOCs);

- The incident rate is increasing over time, roughly doubling each year, which represents an increasing hazard over time;

- Most incidents are reported within 5 NM (9.26 km) of the centre of aerodromes and at excessive altitudes; and

- Most incidents are reported near Canada's busiest major airports, particularly around Toronto and Vancouver.

The study of possible severity of an incident or amount of injury to a person or damage to property is based on test results of a Ground Collision Study conducted under the auspices of the FAA's Centre of Excellence for UAS Research, ASSURE. The potential damage by a UAS to a transport category manned aircraft engine while in flight is modelled after “bird strike” studies. Most of the studies conducted so far are based on numerical models that are compared to bird strike data. The studies conclude that UAS will have more damage potential than equivalent mass birds because unlike birds, which compress and deform on impact, UAS components like cameras, batteries, and motors are much denser and more rigid, and the batteries in particular contain flammable chemicals.

The following discussion presents a more detailed rationale with respect to the individual requirements of the proposed Regulations as acceptable mitigating measures to reduce the risk of incident or accident.

Requirement for pilots

The rationale to require the proposed mitigating measures attributed to pilots are due to the fact that UASs are integrated into airspace shared by manned aircraft. To a lesser degree, the UAS pilot requirements are modelled after the recreational manned aviation industry (Ultra-light aircraft); thus, the proposed requirements for pilots operating UASs in a small complex operating area to have basic aerospace knowledge and skill.

Requirement for UAS designs to meet a minimum standard if operated in the small complex operations category

There is not a lot of data regarding the rate of “fly-away” incidents where a UA would become uncontrollable mid-flight; however, Transport Canada is aware that such incidents are happening. It is assumed that by requiring UASs operated in a small complex operating area to meet minimum design standards would reduce the risk of “fly-away” incidents. Discussion with industry members have led Transport Canada to conclude that mandating design standards for UAs operated in the small complex category is a justified mitigating measure. The UAS operators describe these units as being more reliable, but much more expensive.

Requirement for lateral distances

Lateral distances themselves are mitigating measures to reduce the risk of UAS incidents and accidents. Since there has been an incident of an individual being injured on the head after being hit by a UA as well as an incident of a UAS hitting the front of a moving car, mandating distance offsets to people, vehicles and vessels are considered justified. To reduce the risks of such incidents from happening, the proposed Regulations identify mitigating measures and establish lateral distances commensurate to those mitigating measures. Therefore, lateral distances would be reduced when, for example, the UAS system complies with minimum design standards and the pilot meets knowledge and training requirements. In a limited environment, because there are fewer regulatory requirements for the UAS operator to comply with, those lateral distances are greater to ensure the safety of persons and property. For a complex environment, because the UAS user would have to comply with more stringent requirements, such as holding a pilot permit and operating a UAS that meets aircraft design standards, these lateral distances can be reduced. Where in a small limited environment, the proposed lateral distance requirements would be 250 feet from people, vehicles and vessels, the distance in the context of a small complex operation, would be 100 feet.

Defining a complex environment as related to built-up areas

Transport Canada conducted an analysis that took into account scenarios that could affect the risks of operating a UAS. The analysis took into account how far a UA could fly once a lost link occurred (fly-away), that is the average battery duration as well as the average speed and altitude at which a fly-away could occur. For the analysis, the probability of a UA fly-away occurring is taken as 1 in 40, but some Internet searches found reference to UA fly-away probability as high as 1 in 3.

The present analysis concluded that 0.5 NM was a safe distance to mitigate the risk of a UA hitting a person in a built-up area. The analysis is assumed to be refined as more fly-away data could possibly be collected. Transport Canada has determined based on this analysis that 0.5 NM from the edge of a built-up area is the appropriate distance where increased regulatory requirements would be warranted to ensure safety, thus defining where a small complex environment begins. Transport Canada is aware that the proposed amendment may pose location restrictions for a recreational pilot living within the 0.5 NM (0.93 km) distance limitation of a built-up area and who does not want to meet the more stringent requirements of the complex operating category. However, Transport Canada is confident that the recreational UA pilot would be able to find an appropriate location to operate their UA.

Aeromodelling associations

The following presents a rationale with respect to why the proposed Regulations do not include an exception for MAAC members.

MAAC has a long history of a safety culture, provides continued mentoring and guidance and has insurance for its members. It is Transport Canada's intent to develop criteria for new emerging model associations that can provide to their members the same mentoring as MAAC does. The proposed Regulations would apply to MAAC members until such time as these criteria are developed and further amendments are introduced to carve out those associations. Until the Regulations can be modified to address new and emerging aero-modelling associations, Transport Canada would issue an exemption to MAAC members to the proposed requirements, so as to not negatively impact this sector of the industry.

Summary

While industry continues to innovate and improve UAS design, system integration and utilization, aviation stakeholders are in agreement that the regulations governing UAS pilots, operators and operations have to change. Industry stakeholders, the government and the general public, with the exception of some recreational UAS users, are supportive of amending the regulations and confident their objectives will be met. By introducing these proposed Regulations, Transport Canada is proposing a balanced approach between mitigating safety risks with the possible inconvenience for recreational UAS pilots to find an appropriate location to operate.

While preventing an accident to a manned aircraft would be the most beneficial economically, reducing the need for the SFOC process for operations where a UAS weighs less than 25 kg and thereby reducing what has been an increased service standard for businesses to obtain permission to operate would also prove to be economically beneficial.

The reduced administrative burden is expected to increase the number of non-recreational (commercial) UAS operators to be compliant with UAS regulations in general.

Implementation, enforcement and service standards

The proposed Regulations would come into force six months after the day on which they are published in the Canada Gazette, Part II. Transport Canada expects that personnel to process the UAS pilot permit requests will be available by the time the proposed Regulations come into effect and that a registration system for UASs for small complex operation be in place. The service standard for the issuance of a UAS pilot permit could be between 20 and 40 working days and between 7 and 60 working days for the issuance of a UAS certificate of registration, but an email confirmation could be used temporarily.

Transport Canada would authorize external law enforcement agencies pursuant to section 4.3 of the Aeronautics Act to issue administrative monetary penalties (AMPs) for designated offences to complement enforcement actions by Transport Canada inspectorate. Such an approach would be consistent with and complement Transport Canada's enforcement program.

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) would be first granted authorization to administer AMPs for non-compliance. The Department may also pursue similar partnerships with provinces, territories and municipalities, including bylaw officers, if UAV-related incidents continue to increase and additional enforcement capacity is required.

Following the coming into force of the Regulations, Transport Canada would conduct a concentrated enforcement campaign in areas where reports of unmanned aircraft incidents are at the highest frequency. Through this campaign, the Department would seek to educate users on their legal responsibilities, while also taking enforcement action should non-compliance be identified. This could range from verbal warnings to the issuance of administrative monetary penalties.

In addition to the enforcement strategy, Transport Canada would continue to actively conduct an education and outreach campaign to improve compliance. The Department would continue to build upon the “Safety First” web page, created in 2015, to provide tools for Canadians and to increase awareness of the risks associated with flying a UAV. The Department would work with the retail Council of Canada and point-of-sale retailers to provide consumers with information and to promote safety practices.

These proposed amendments would be enforced through the assessment of AMPs imposed under sections 7.6 to 8.2 of the Aeronautics Act, which carry a maximum fine of $3,000 for individuals and $25,000 for corporations, through suspension or cancellation of a Canadian aviation document, or through judicial action introduced by way of summary conviction, as per section 7.3 of the Aeronautics Act.

Contact

Chief

Regulatory Affairs, AARBH

Civil Aviation

Safety and Security

Transport Canada

Place de Ville, Tower C